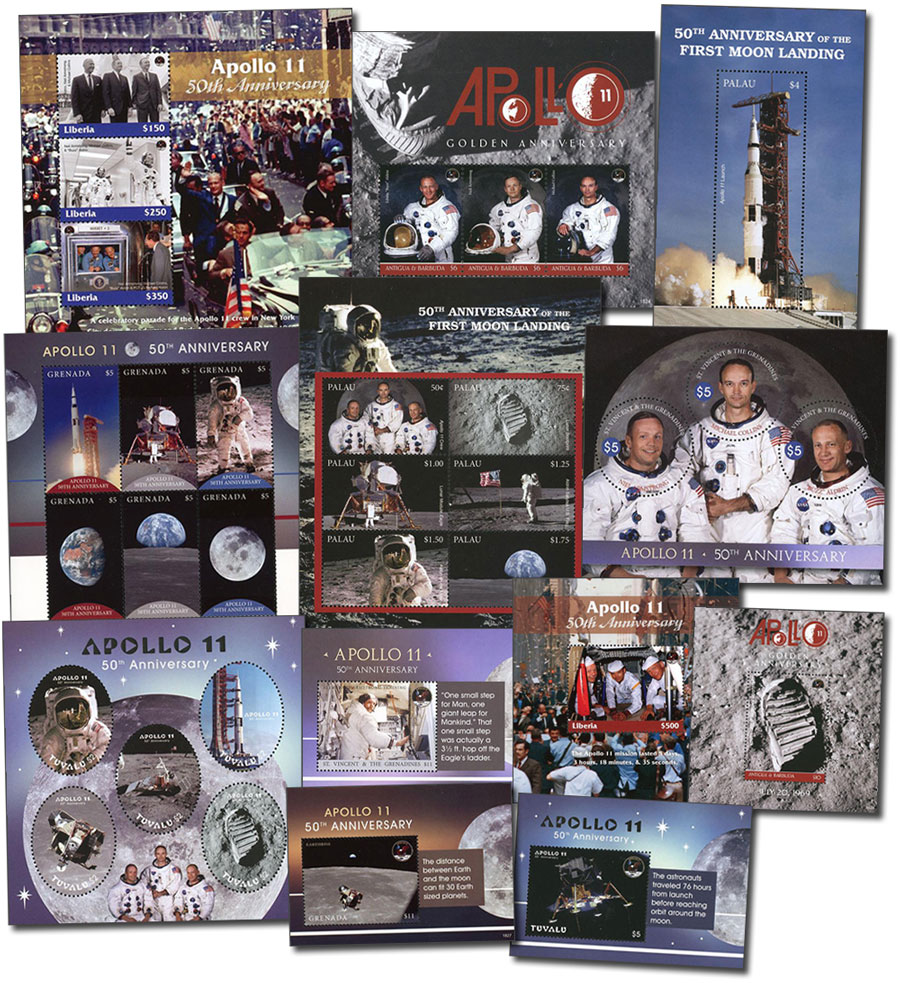

# M12488 - US Stamps Celebrate Moon Landing - 36 mint stamps included

Relive the Excitement of the Moon Landing with Mint 50th Anniversary Set

Now you can get a mint collector's set of US stamps honoring one of man's greatest achievements. On July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first people to land on the moon. It was one of the most significant events of the 20th century and it paved the way for all space exploration since.

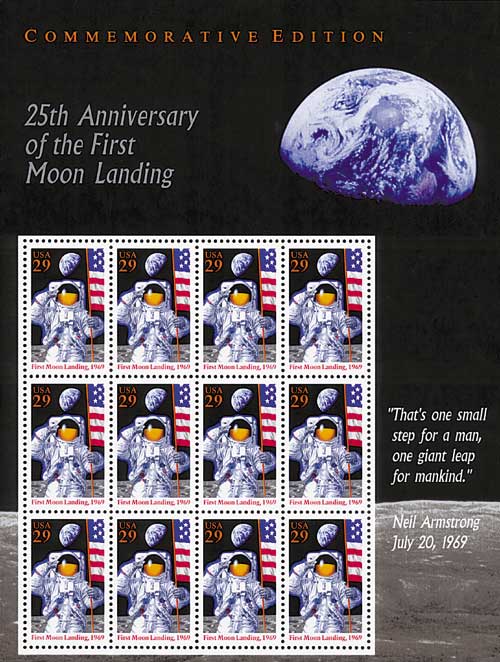

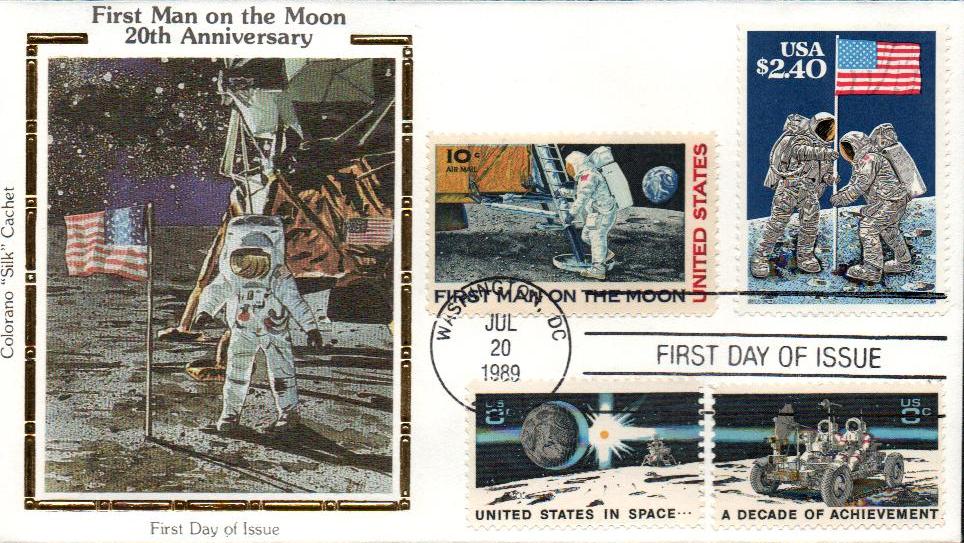

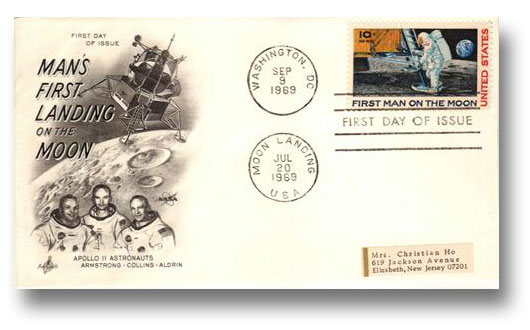

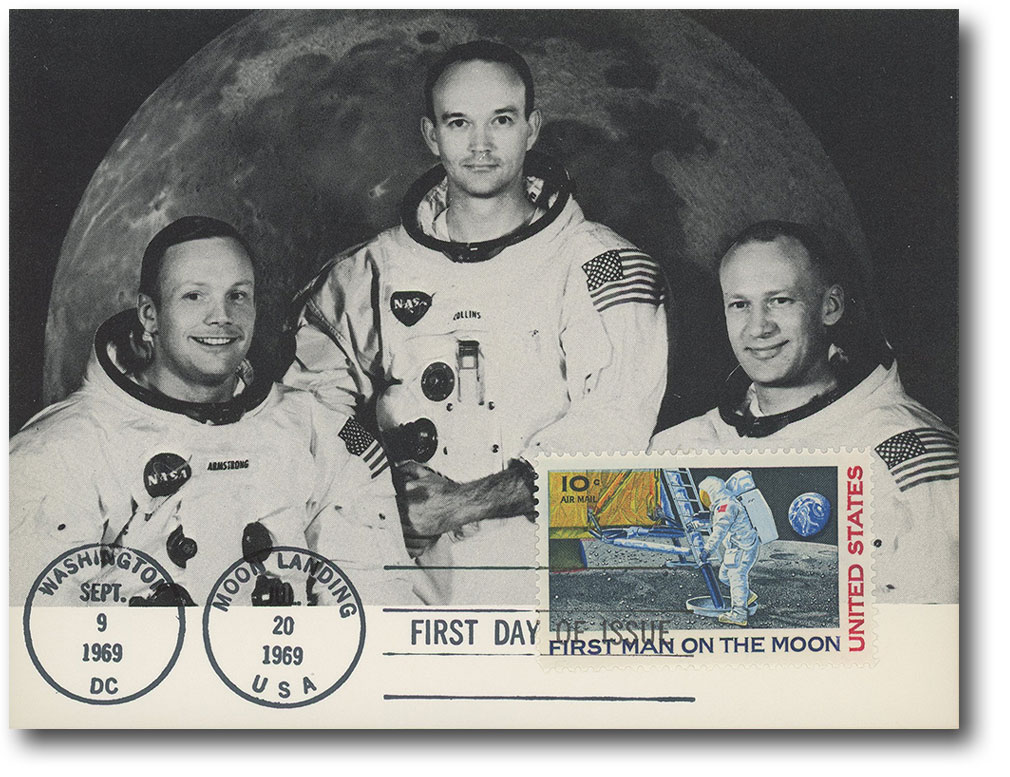

This is your chance to own US Scott #C76, 1371, 1434-35, 1912-19, 2419, 2631-34, 2841, 2842, 3188c, 3413, and the two 2019 Moon Landing 50th Anniversary stamps – all in mint condition – in one easy order. You'll get one attached pair, a se-tenant of eight, a se-tenant of four, a sheet of 12, and a souvenir sheet of one, plus five single stamps. Plus, we'll include Scott #1331-32, the 1967 5 cent "Space Twins" stamps, for FREE. That's 36 stamps in all!

There's no better time to get this historic Moon Landing set than right now.

U.S. Lands First Men On The Moon

On July 20, 1969, the US effectively won the Space Race when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed the Eagle lunar module on the Moon’s surface.

The space race began 12 years earlier, on October 4, 1957, when the Soviet Union used rocket technology developed by the Germans in World War II to launch Sputnik, the world’s first artificial satellite. Originally, Sputnik was intended to be a massive, thousand-pound satellite. However, because the Americans were attempting to launch their own satellite, the decision was made to scale back the design considerably. At the time of launch, Sputnik was no bigger than a basketball.

Success continued for the Soviets during the next few years, prompting President John F. Kennedy to push NASA to place a man on the Moon before the end of the decade. Kennedy’s challenge was no small feat. At the time, the US space program wasn’t prepared for such an undertaking. There were no rockets, spacesuits, or computers capable of the task. NASA scientists didn’t know what they’d need to accomplish the goal, but they stepped up to the challenge. Hundreds of thousands of scientists and engineers joined together to achieve something many thought was impossible.

After thousands of hours of work over eight years, NASA launched Apollo 11 on July 16, 1969. Four days later, on July 20, 1969, their Eagle lunar module approached the Moon. The landing module touched down in a place called “West Crater,” which was scattered with boulders. After the landing, Aldrin requested everyone “…to pause for a moment and contemplate the events of the past few hours and to give thanks in his or her own way.”

Aldrin, who was an elder in his church, then proceeded to receive Communion from a kit prepared for him by his pastor. This was blacked out of the broadcast due to an ongoing lawsuit filed against NASA concerning the crew of the Apollo 8 mission reading from the Book of Genesis.

After the landing was completed, the crew began preparations for the Moonwalk. They had originally planned a five-hour sleep period, but it was decided they would be too excited to sleep.

Then, at 10:56 p.m. EDT, Armstrong set his left foot down upon the surface of the Moon and called it, “…one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.” Fellow astronaut Buzz Aldrin joined Armstrong on the surface and described the scene as “magnificent desolation.” Back on Earth, the world watched through a live television feed.

The Moonwalk wasn’t just symbolic – Armstrong and Aldrin had several tasks to perform. One of them included planting the American flag. They first had to get used to walking around on the Moon. They took photographs, collected rock, and dust samples and set out equipment to transmit readings. After about two-and-a-half hours, they returned to the landing module. After taking off their spacesuits they noticed a strange smell in the air. Armstrong described it as wet ashes and Aldrin said it was like “the smell in the air after a firecracker has gone off.” It was the smell of the Moon dust. Scientists had been concerned that the dust might ignite when it came in contact with oxygen when the module re-pressurized, but luckily, that wasn’t the case. Armstrong and Aldrin then took a much-deserved rest.

But this was the era of the Space Race, and the Soviet Union had launched an unmanned spacecraft three days before the Apollo 11 mission took off. As the US astronauts slept, Luna 15 began its descent to the Moon’s surface. It was the third attempt by the Soviets to collect lunar soil, and the third failure. Luna 15 crashed into the Moon, likely on the side of a mountain.

After their rest, Armstrong and Aldrin blasted off from the Moon’s surface – unfortunately toppling the American flag they had planted. In future lunar landings, the flag was placed no closer than 100 feet from the modules, so as not to repeat that mistake.

The Eagle docked with the Columbia, where fellow astronaut Michael Collins had been waiting. The Eagle was released into orbit around the Moon, and NASA scientists later assumed that it crashed to the surface after a few months.

The Columbia command module, a 10-foot-long cone, was all that remained of the massive Saturn V rocket that began the journey. The Saturn V was 363 feet long and weighed 6,699,000 pounds (Columbia weighed 13,000 pounds). The journey home lasted three days, and the crew had to make only one correction.

On July 24, the command module separated and began its descent to Earth. The bottom of the module faced the surface and had special heat shields that would burn away during re-entry, to prevent the build-up of heat. The parachute opened after 195 hours and 13 minutes in space. The Apollo 11 crew splashed down in the Pacific Ocean, where Navy ship USS Hornet was nearby. They were finally home and President Kennedy’s vision was realized. America had effectively won the Space Race and was ready to embark on a new era in space exploration.

Relive the Excitement of the Moon Landing with Mint 50th Anniversary Set

Now you can get a mint collector's set of US stamps honoring one of man's greatest achievements. On July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first people to land on the moon. It was one of the most significant events of the 20th century and it paved the way for all space exploration since.

This is your chance to own US Scott #C76, 1371, 1434-35, 1912-19, 2419, 2631-34, 2841, 2842, 3188c, 3413, and the two 2019 Moon Landing 50th Anniversary stamps – all in mint condition – in one easy order. You'll get one attached pair, a se-tenant of eight, a se-tenant of four, a sheet of 12, and a souvenir sheet of one, plus five single stamps. Plus, we'll include Scott #1331-32, the 1967 5 cent "Space Twins" stamps, for FREE. That's 36 stamps in all!

There's no better time to get this historic Moon Landing set than right now.

U.S. Lands First Men On The Moon

On July 20, 1969, the US effectively won the Space Race when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed the Eagle lunar module on the Moon’s surface.

The space race began 12 years earlier, on October 4, 1957, when the Soviet Union used rocket technology developed by the Germans in World War II to launch Sputnik, the world’s first artificial satellite. Originally, Sputnik was intended to be a massive, thousand-pound satellite. However, because the Americans were attempting to launch their own satellite, the decision was made to scale back the design considerably. At the time of launch, Sputnik was no bigger than a basketball.

Success continued for the Soviets during the next few years, prompting President John F. Kennedy to push NASA to place a man on the Moon before the end of the decade. Kennedy’s challenge was no small feat. At the time, the US space program wasn’t prepared for such an undertaking. There were no rockets, spacesuits, or computers capable of the task. NASA scientists didn’t know what they’d need to accomplish the goal, but they stepped up to the challenge. Hundreds of thousands of scientists and engineers joined together to achieve something many thought was impossible.

After thousands of hours of work over eight years, NASA launched Apollo 11 on July 16, 1969. Four days later, on July 20, 1969, their Eagle lunar module approached the Moon. The landing module touched down in a place called “West Crater,” which was scattered with boulders. After the landing, Aldrin requested everyone “…to pause for a moment and contemplate the events of the past few hours and to give thanks in his or her own way.”

Aldrin, who was an elder in his church, then proceeded to receive Communion from a kit prepared for him by his pastor. This was blacked out of the broadcast due to an ongoing lawsuit filed against NASA concerning the crew of the Apollo 8 mission reading from the Book of Genesis.

After the landing was completed, the crew began preparations for the Moonwalk. They had originally planned a five-hour sleep period, but it was decided they would be too excited to sleep.

Then, at 10:56 p.m. EDT, Armstrong set his left foot down upon the surface of the Moon and called it, “…one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.” Fellow astronaut Buzz Aldrin joined Armstrong on the surface and described the scene as “magnificent desolation.” Back on Earth, the world watched through a live television feed.

The Moonwalk wasn’t just symbolic – Armstrong and Aldrin had several tasks to perform. One of them included planting the American flag. They first had to get used to walking around on the Moon. They took photographs, collected rock, and dust samples and set out equipment to transmit readings. After about two-and-a-half hours, they returned to the landing module. After taking off their spacesuits they noticed a strange smell in the air. Armstrong described it as wet ashes and Aldrin said it was like “the smell in the air after a firecracker has gone off.” It was the smell of the Moon dust. Scientists had been concerned that the dust might ignite when it came in contact with oxygen when the module re-pressurized, but luckily, that wasn’t the case. Armstrong and Aldrin then took a much-deserved rest.

But this was the era of the Space Race, and the Soviet Union had launched an unmanned spacecraft three days before the Apollo 11 mission took off. As the US astronauts slept, Luna 15 began its descent to the Moon’s surface. It was the third attempt by the Soviets to collect lunar soil, and the third failure. Luna 15 crashed into the Moon, likely on the side of a mountain.

After their rest, Armstrong and Aldrin blasted off from the Moon’s surface – unfortunately toppling the American flag they had planted. In future lunar landings, the flag was placed no closer than 100 feet from the modules, so as not to repeat that mistake.

The Eagle docked with the Columbia, where fellow astronaut Michael Collins had been waiting. The Eagle was released into orbit around the Moon, and NASA scientists later assumed that it crashed to the surface after a few months.

The Columbia command module, a 10-foot-long cone, was all that remained of the massive Saturn V rocket that began the journey. The Saturn V was 363 feet long and weighed 6,699,000 pounds (Columbia weighed 13,000 pounds). The journey home lasted three days, and the crew had to make only one correction.

On July 24, the command module separated and began its descent to Earth. The bottom of the module faced the surface and had special heat shields that would burn away during re-entry, to prevent the build-up of heat. The parachute opened after 195 hours and 13 minutes in space. The Apollo 11 crew splashed down in the Pacific Ocean, where Navy ship USS Hornet was nearby. They were finally home and President Kennedy’s vision was realized. America had effectively won the Space Race and was ready to embark on a new era in space exploration.