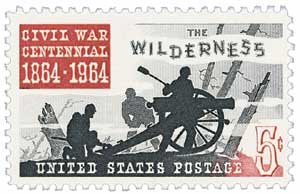

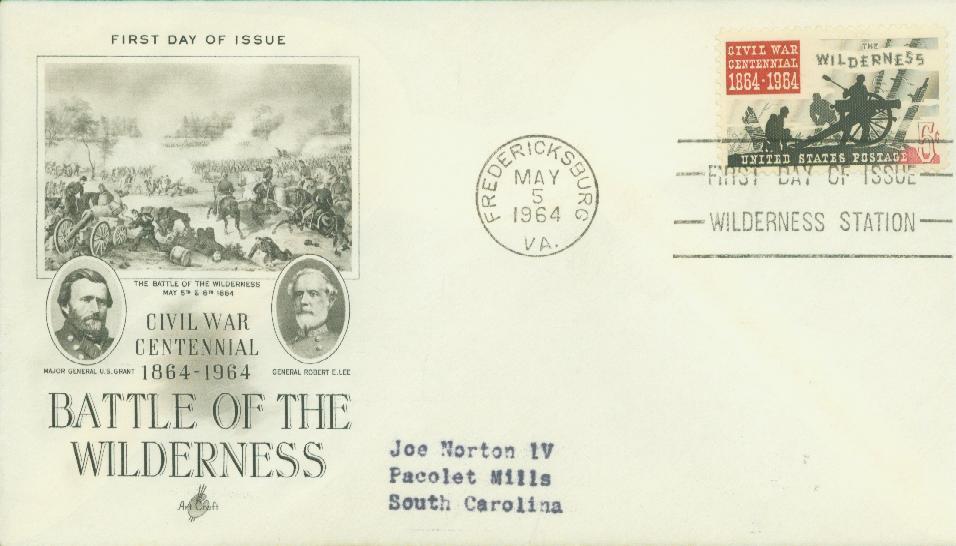

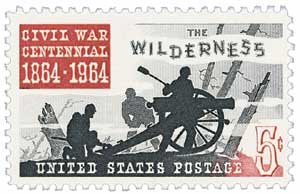

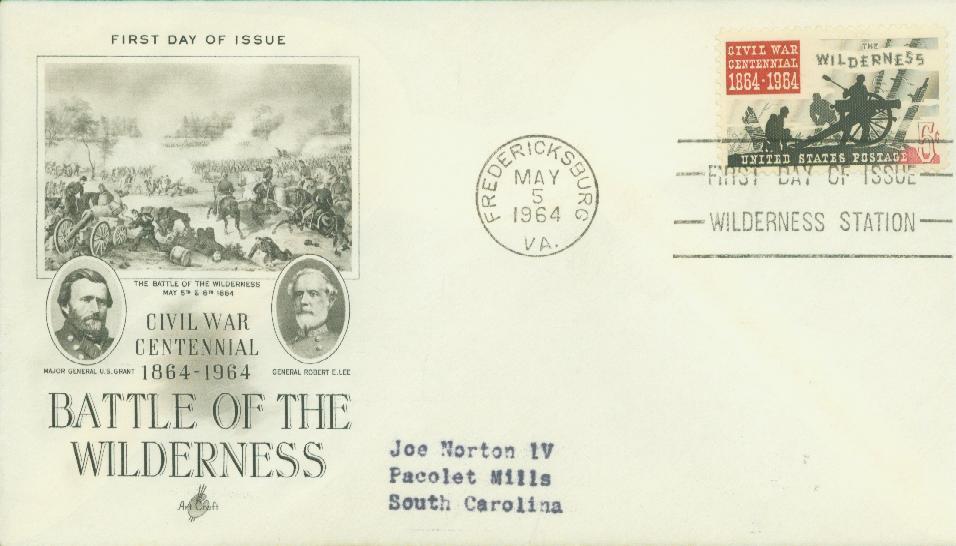

# 1181 - 1964 5c Civil War Centennial: Battle of the Wilderness

5¢ Battle of the Wilderness

Civil War Centennial Issue

City: Fredericksburg, VA

Printed By: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Giori Press

Perforations: 11

Color: Dark red and black

Battle Of The Wilderness

On May 5, 1864, Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee clashed at the Battle of the Wilderness in Virginia.

Grant had been made commander of all Union armies in March 1864. His goal was to destroy the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, which should, in turn, lead to the fall of Richmond. That spring, he launched his Overland Campaign in pursuit of General Lee.

On May 4, Grant’s men crossed the Rapidan River. The area would have been familiar to veterans of the Army of the Potomac – as one year earlier they had lost the Battle of Chancellorsville in the same county. Grant planned to move to open ground before attacking, unwilling to take on the Confederates in the dense forest called the Wilderness. One writer later said, “In this near-jungle, the Confederates had the advantages of being, on the whole, better woodsmen than their opponents and of being far more familiar with the terrain.”

Meanwhile, General Lee and his corps commanders were watching the movement of the Union Army from nearby Clark Mountain. He knew they were ready to attack, but was not sure where. Unlike Grant, Lee favored fighting in the Wilderness, knowing the Union could not use their artillery. He ordered his army to march along two parallel roads to intercept the enemy on his chosen terrain.

Confederate Lieutenant General Richard Ewell marched his Second Corps east along the Orange Turnpike. In the early hours of May 5, they met Major General Gouverneur Warren’s V Corps. Ewell’s men quickly set up earthworks for protection. Warren’s troops outnumbered the Rebels, but the defensive position gave the smaller force an advantage. Much of the day’s fighting was at close range and in the midst, the field caught fire, trapping the wounded. The guns quieted as night fell and neither side had gained ground.

While Ewell and Warren were locked in combat in the Orange Turnpike, other corps were conducting maneuvers of their own three miles to the south along the Orange Plank Road. Lieutenant General A.P. Hill and his Confederate Third Corps traveled east toward Brock Road. If they secured the intersection, they would cut off the II Corps from the rest of the Union Army. Grant realized the plan and sent a division to defend the roadway. They arrived in time to hold off Hill’s forces with the help of the II Corps under the command of Major General Winfield Hancock. The Rebels were driven back until darkness fell and fighting ended.

As the sun rose the next morning, Grant expected to overcome Hill’s worn-down forces on the Orange Plank Road. He ordered Hancock’s men to begin the attack at 5 AM, and the Confederates were soon fleeing to the rear. Before Hill’s troops were destroyed, Lieutenant General James Longstreet’s First Corps arrived to reinforce the Rebels. In the excitement of the battle, General Lee steered his horse toward the front lines but was persuaded to find a safer location to watch the action. While most of the First Corps forced the Union back, Longstreet found an unfinished railroad bed to the south of the action and took four brigades around the enemy’s left flank. The surprise assault was effective as it rolled up the line “like a wet blanket,” as Hancock later recounted. The Union was pushed back to the Brock Road. As Longstreet and his officers rode along the Plank Road, some of the men returning from the surprise attack mistook the group for Union soldiers and fired on them, severely wounding the general in the neck.

Fighting had also resumed to the north of the Plank Road. Continuing throughout most of the day, neither side gained the upper hand. Shortly before nightfall, Confederate Brigadier General John Gordon attacked Grant’s unprotected right flank. He captured two Union generals and pushed the line back, but darkness fell and the Northern Army was reinforced during the night.

Realizing the strength of the Confederate’s defensive position, Grant ordered the Union Army to move south on the Brock Road. The veterans had been in similar situations before and expected to march back across the river in retreat. Instead, Grant ordered his men to head to Spotsylvania Court House in the hopes of getting between Lee and Richmond. The decision met with cheers from the Northern troops who now realized they were under the command of a new, courageous leader.

From Lee’s vantage point, he saw the direction the Union was headed. He sent Major General Anderson, who now commanded Longstreet’s corps, to intercept the enemy at the important crossroads. The two armies met again a few days later to continue the Overland Campaign.

5¢ Battle of the Wilderness

Civil War Centennial Issue

City: Fredericksburg, VA

Printed By: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Giori Press

Perforations: 11

Color: Dark red and black

Battle Of The Wilderness

On May 5, 1864, Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee clashed at the Battle of the Wilderness in Virginia.

Grant had been made commander of all Union armies in March 1864. His goal was to destroy the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, which should, in turn, lead to the fall of Richmond. That spring, he launched his Overland Campaign in pursuit of General Lee.

On May 4, Grant’s men crossed the Rapidan River. The area would have been familiar to veterans of the Army of the Potomac – as one year earlier they had lost the Battle of Chancellorsville in the same county. Grant planned to move to open ground before attacking, unwilling to take on the Confederates in the dense forest called the Wilderness. One writer later said, “In this near-jungle, the Confederates had the advantages of being, on the whole, better woodsmen than their opponents and of being far more familiar with the terrain.”

Meanwhile, General Lee and his corps commanders were watching the movement of the Union Army from nearby Clark Mountain. He knew they were ready to attack, but was not sure where. Unlike Grant, Lee favored fighting in the Wilderness, knowing the Union could not use their artillery. He ordered his army to march along two parallel roads to intercept the enemy on his chosen terrain.

Confederate Lieutenant General Richard Ewell marched his Second Corps east along the Orange Turnpike. In the early hours of May 5, they met Major General Gouverneur Warren’s V Corps. Ewell’s men quickly set up earthworks for protection. Warren’s troops outnumbered the Rebels, but the defensive position gave the smaller force an advantage. Much of the day’s fighting was at close range and in the midst, the field caught fire, trapping the wounded. The guns quieted as night fell and neither side had gained ground.

While Ewell and Warren were locked in combat in the Orange Turnpike, other corps were conducting maneuvers of their own three miles to the south along the Orange Plank Road. Lieutenant General A.P. Hill and his Confederate Third Corps traveled east toward Brock Road. If they secured the intersection, they would cut off the II Corps from the rest of the Union Army. Grant realized the plan and sent a division to defend the roadway. They arrived in time to hold off Hill’s forces with the help of the II Corps under the command of Major General Winfield Hancock. The Rebels were driven back until darkness fell and fighting ended.

As the sun rose the next morning, Grant expected to overcome Hill’s worn-down forces on the Orange Plank Road. He ordered Hancock’s men to begin the attack at 5 AM, and the Confederates were soon fleeing to the rear. Before Hill’s troops were destroyed, Lieutenant General James Longstreet’s First Corps arrived to reinforce the Rebels. In the excitement of the battle, General Lee steered his horse toward the front lines but was persuaded to find a safer location to watch the action. While most of the First Corps forced the Union back, Longstreet found an unfinished railroad bed to the south of the action and took four brigades around the enemy’s left flank. The surprise assault was effective as it rolled up the line “like a wet blanket,” as Hancock later recounted. The Union was pushed back to the Brock Road. As Longstreet and his officers rode along the Plank Road, some of the men returning from the surprise attack mistook the group for Union soldiers and fired on them, severely wounding the general in the neck.

Fighting had also resumed to the north of the Plank Road. Continuing throughout most of the day, neither side gained the upper hand. Shortly before nightfall, Confederate Brigadier General John Gordon attacked Grant’s unprotected right flank. He captured two Union generals and pushed the line back, but darkness fell and the Northern Army was reinforced during the night.

Realizing the strength of the Confederate’s defensive position, Grant ordered the Union Army to move south on the Brock Road. The veterans had been in similar situations before and expected to march back across the river in retreat. Instead, Grant ordered his men to head to Spotsylvania Court House in the hopes of getting between Lee and Richmond. The decision met with cheers from the Northern troops who now realized they were under the command of a new, courageous leader.

From Lee’s vantage point, he saw the direction the Union was headed. He sent Major General Anderson, who now commanded Longstreet’s corps, to intercept the enemy at the important crossroads. The two armies met again a few days later to continue the Overland Campaign.