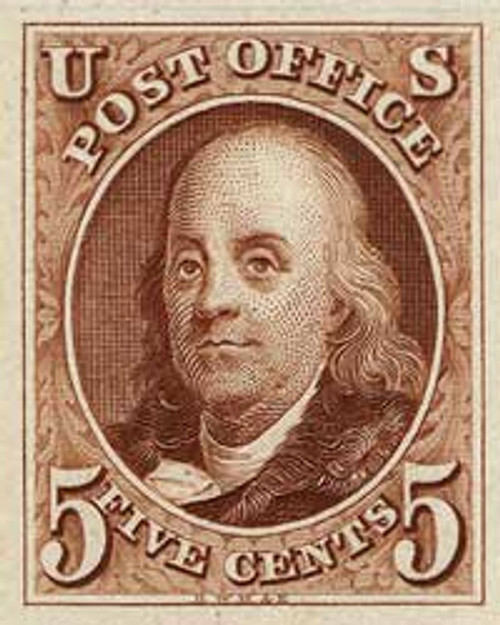

1847 5c Benjamin Frank, Orange Brown, Imperforate

# 1b - 1847 5c Benjamin Frank, Orange Brown, Imperforate

$725.00 - $1,495.00

U.S. #1b

1847 Benjamin Franklin

- America’s First Postage Stamp

- Vignette features the portrait of Benjamin Franklin, “Father of America’s Postal Service” and first Postmaster General of the United States

- In demand around the world and increasingly scarce today in any condition

Stamp Category: Definitive

Set: 1847 Issue

Value: 5c – the half-ounce letter rate (up to 300 miles)

First Day of Issue: July 1, 1847

First Day City: New York City

Quantity Issued: 3,600,000 (Estimated)

Printed by: Rawden, Wright, Hatch & Edson

Printing Method: Engraved; Flat plate printing

Format: Sheet of 200 subjects in 2 panes of 100 each

Perforations: Imperforate

Color: Orangebrown on thin, bluish wove paper. The printing of U.S. #1 produced this minor color variety, plus three others – #1a dark brown, #1c (red orange) and #1d (brown orange.) Several other shades have been noted, but only these are listed in Scott’s Specialized Catalogue of United States Stamps as minor varieties of U.S. #1.

Printers Rawden, Wright, Hatch, & Edson originally suggested printing the stamp in two colors.

Why the stamp was issued: To show prepayment of the uniform domestic postage fee of 5 cents for letters weighing up to ½-ounce and sent up to 300 miles.

There are a number of reasons why modernization of America’s postal service was urgently needed. A few of these include the steady flow of immigrants from Europe, the on-going settlement of the West, the Mexican-American War, industrial growth, and conflicts between the states on the issue of slavery. All called for more a rapid and dependable flow of communication.

About the stamp design: The printing dies for U.S. #1 were already in the stocks of the printers, who had previously used them to produce private banknotes. The portrait of Benjamin Franklin was based on a painting by James B. Longacre. Longacre (1794-1869) was not only a portraitist, but also an engraver, becoming the fourth Chief Engraver of the U.S. Mint. The engraving was done by Asher B. Durand, a well-known American landscape painter. One of the founders of the Hudson River School, Durand also founded the National Academy of Design.

Special design details: The initials of the printers – RWH&E – appear at the bottom of the stamp, centered inside the frame line.

About the printing process: U.S. #1 was printed by hand, which consisted of line engraving the design onto the steel plate of a flat bed press. The plate was inked and heated. A sheet of damp paper was laid on the plate. A heavy wooden or metal piece on the press, called a platen, was rolled over the plate, transferring the ink to the paper. Each sheet was put aside to dry. All the work was done manually, making for a slow process and only a few thousand stamps printed each day. The early flat bed (or flat plate) press was called a “Spider” press.

The weak impression found on many U.S. #1 stamps is due to a number of small particles of quartz mixed with the ink. These particles wore the steel plates down, causing the impression to be less sharp.

Stamps printed by the flat plate method will often have telltale traces of ink on the back. This is due to the sheets having been laid on top of one another before they were completely dry. Ink often transferred from the front of the bottom sheet to the back of the top sheet. Another clue to identifying stamps printed on a flat plate press is being able to feel the raised ink on its surface.

First Day City: U.S. #1 was issued in New York City. The stamps were sold in Boston on July 2nd and Philadelphia on July 7th. First documented use of U.S. #1 was July 7, 1847, six days after its issue date.

Margins: The first U.S. postage stamps were issued in large sheets without perforations. Postal clerks simply cut the stamps from the sheet by hand. This accounts for the large variation in margins seen on U.S. #1. Well-centered stamps with large margins are sold at a higher price due to their scarcity.

Prior to the issue of U.S. #1 and #2, a few postage stamps were issued privately by various postmasters. These were called “Postmaster Provisionals”. Once the first two federal postage stamps were issued, provisionals were no longer valid.

If a letter was sent without stamps, marked with the amount to be paid upon receipt or “postage due”, it’s called a stampless cover.

Before the introduction of envelopes, postal customers would either fold a piece of paper around their letters in the shape of an envelope, or fold the letter itself and apply an adhesive or wax seal. Envelopes are referred to as covers. A U.S. #1 “on cover” is very scarce and worth a lot of money.

About the 1847 Imperforates – U.S. #1 and #2: It may seem surprising George Washington doesn’t appear on our first postage stamp. But Franklin was highly esteemed for his service in establishing America’s postal system. After serving as postmaster of Philadelphia, he was co-postmaster general for the colonies under British rule. Finally, Franklin was appointed America’s first postmaster general by the 2nd Continental Congress. In addition to his accomplishments in the postal area, he was the central unifying figure for the colonists during the Revolution. That made Franklin a logical choice. This brilliant scientist, diplomat, statesman, printer, inventor, and patriot earned his place in history, as well as on America’s first postage stamp.

Andrew Jackson was the original choice for the subject of US#1.

President George Washington’s 10c stamp (U.S. #2) was issued the same day. At 10c it was twice the face value. His portrait has appeared on over 300 U.S. stamps, more than any other president and more than all other presidents combined.

History the stamp represents: America followed Great Britain by just a few years when it issued our first general issue pre-paid adhesive postage stamps. These stamps changed our postal service forever – the newest step in making it easier and more efficient to send, receive and deliver the mail. This in turn vastly improved communications across our rapidly expanding country. It was expensive to print the stamps, but cheaper and more efficient to handle the mail.

A stamp to show the pre-payment of postage did away with the need for postmasters to count the number of pages in a letter, and mark the fee on the envelope according to its weight and how far it would travel. Now customers could buy stamps in advance without waiting in line, and drop their letters off in the post office box any time. And the recipient was no longer required to pay the fee at his post office when he picked the letter up. (It wasn’t until years later, in July 1863, that free city delivery to individual addresses became available.) Pre-paid postage stamps also enabled postal authorities to track sales and have more control over money taken in.

Prepayment with a general issue stamp did not become mandatory until January 1st, 1856. Before this time, it was still legal for the addressee to pay the postage or for the sender and recipient to share the cost.

More about Benjamin Franklin’s role in history: In addition to establishing the American colonies’ postal system, and later becoming our first postmaster general, Benjamin Franklin was one of our country’s greatest patriots and founding fathers. His diplomacy and negotiating skills were pivotal in persuading France to become our ally in the fight against the British. This profoundly affected the outcome of the American Revolution. Franklin also contributed significantly to the creation of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. He signed both, as well as the Treaty of Alliance with France, and the Treaty of Paris, which ended the American Revolution. No other statesman had the honor of signing of all four pivotal documents. And few played as important a role as Ben Franklin in the events which led to their signing.

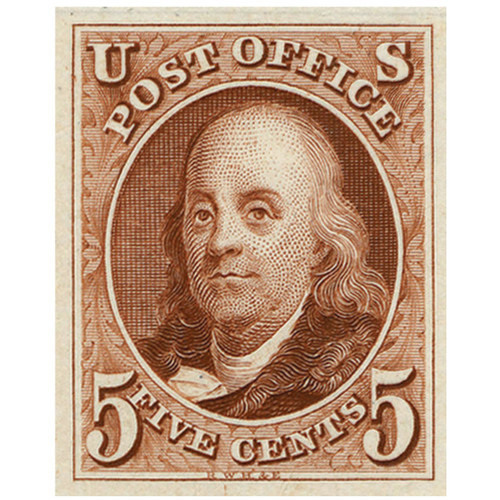

U.S. #1b

1847 Benjamin Franklin

- America’s First Postage Stamp

- Vignette features the portrait of Benjamin Franklin, “Father of America’s Postal Service” and first Postmaster General of the United States

- In demand around the world and increasingly scarce today in any condition

Stamp Category: Definitive

Set: 1847 Issue

Value: 5c – the half-ounce letter rate (up to 300 miles)

First Day of Issue: July 1, 1847

First Day City: New York City

Quantity Issued: 3,600,000 (Estimated)

Printed by: Rawden, Wright, Hatch & Edson

Printing Method: Engraved; Flat plate printing

Format: Sheet of 200 subjects in 2 panes of 100 each

Perforations: Imperforate

Color: Orangebrown on thin, bluish wove paper. The printing of U.S. #1 produced this minor color variety, plus three others – #1a dark brown, #1c (red orange) and #1d (brown orange.) Several other shades have been noted, but only these are listed in Scott’s Specialized Catalogue of United States Stamps as minor varieties of U.S. #1.

Printers Rawden, Wright, Hatch, & Edson originally suggested printing the stamp in two colors.

Why the stamp was issued: To show prepayment of the uniform domestic postage fee of 5 cents for letters weighing up to ½-ounce and sent up to 300 miles.

There are a number of reasons why modernization of America’s postal service was urgently needed. A few of these include the steady flow of immigrants from Europe, the on-going settlement of the West, the Mexican-American War, industrial growth, and conflicts between the states on the issue of slavery. All called for more a rapid and dependable flow of communication.

About the stamp design: The printing dies for U.S. #1 were already in the stocks of the printers, who had previously used them to produce private banknotes. The portrait of Benjamin Franklin was based on a painting by James B. Longacre. Longacre (1794-1869) was not only a portraitist, but also an engraver, becoming the fourth Chief Engraver of the U.S. Mint. The engraving was done by Asher B. Durand, a well-known American landscape painter. One of the founders of the Hudson River School, Durand also founded the National Academy of Design.

Special design details: The initials of the printers – RWH&E – appear at the bottom of the stamp, centered inside the frame line.

About the printing process: U.S. #1 was printed by hand, which consisted of line engraving the design onto the steel plate of a flat bed press. The plate was inked and heated. A sheet of damp paper was laid on the plate. A heavy wooden or metal piece on the press, called a platen, was rolled over the plate, transferring the ink to the paper. Each sheet was put aside to dry. All the work was done manually, making for a slow process and only a few thousand stamps printed each day. The early flat bed (or flat plate) press was called a “Spider” press.

The weak impression found on many U.S. #1 stamps is due to a number of small particles of quartz mixed with the ink. These particles wore the steel plates down, causing the impression to be less sharp.

Stamps printed by the flat plate method will often have telltale traces of ink on the back. This is due to the sheets having been laid on top of one another before they were completely dry. Ink often transferred from the front of the bottom sheet to the back of the top sheet. Another clue to identifying stamps printed on a flat plate press is being able to feel the raised ink on its surface.

First Day City: U.S. #1 was issued in New York City. The stamps were sold in Boston on July 2nd and Philadelphia on July 7th. First documented use of U.S. #1 was July 7, 1847, six days after its issue date.

Margins: The first U.S. postage stamps were issued in large sheets without perforations. Postal clerks simply cut the stamps from the sheet by hand. This accounts for the large variation in margins seen on U.S. #1. Well-centered stamps with large margins are sold at a higher price due to their scarcity.

Prior to the issue of U.S. #1 and #2, a few postage stamps were issued privately by various postmasters. These were called “Postmaster Provisionals”. Once the first two federal postage stamps were issued, provisionals were no longer valid.

If a letter was sent without stamps, marked with the amount to be paid upon receipt or “postage due”, it’s called a stampless cover.

Before the introduction of envelopes, postal customers would either fold a piece of paper around their letters in the shape of an envelope, or fold the letter itself and apply an adhesive or wax seal. Envelopes are referred to as covers. A U.S. #1 “on cover” is very scarce and worth a lot of money.

About the 1847 Imperforates – U.S. #1 and #2: It may seem surprising George Washington doesn’t appear on our first postage stamp. But Franklin was highly esteemed for his service in establishing America’s postal system. After serving as postmaster of Philadelphia, he was co-postmaster general for the colonies under British rule. Finally, Franklin was appointed America’s first postmaster general by the 2nd Continental Congress. In addition to his accomplishments in the postal area, he was the central unifying figure for the colonists during the Revolution. That made Franklin a logical choice. This brilliant scientist, diplomat, statesman, printer, inventor, and patriot earned his place in history, as well as on America’s first postage stamp.

Andrew Jackson was the original choice for the subject of US#1.

President George Washington’s 10c stamp (U.S. #2) was issued the same day. At 10c it was twice the face value. His portrait has appeared on over 300 U.S. stamps, more than any other president and more than all other presidents combined.

History the stamp represents: America followed Great Britain by just a few years when it issued our first general issue pre-paid adhesive postage stamps. These stamps changed our postal service forever – the newest step in making it easier and more efficient to send, receive and deliver the mail. This in turn vastly improved communications across our rapidly expanding country. It was expensive to print the stamps, but cheaper and more efficient to handle the mail.

A stamp to show the pre-payment of postage did away with the need for postmasters to count the number of pages in a letter, and mark the fee on the envelope according to its weight and how far it would travel. Now customers could buy stamps in advance without waiting in line, and drop their letters off in the post office box any time. And the recipient was no longer required to pay the fee at his post office when he picked the letter up. (It wasn’t until years later, in July 1863, that free city delivery to individual addresses became available.) Pre-paid postage stamps also enabled postal authorities to track sales and have more control over money taken in.

Prepayment with a general issue stamp did not become mandatory until January 1st, 1856. Before this time, it was still legal for the addressee to pay the postage or for the sender and recipient to share the cost.

More about Benjamin Franklin’s role in history: In addition to establishing the American colonies’ postal system, and later becoming our first postmaster general, Benjamin Franklin was one of our country’s greatest patriots and founding fathers. His diplomacy and negotiating skills were pivotal in persuading France to become our ally in the fight against the British. This profoundly affected the outcome of the American Revolution. Franklin also contributed significantly to the creation of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. He signed both, as well as the Treaty of Alliance with France, and the Treaty of Paris, which ended the American Revolution. No other statesman had the honor of signing of all four pivotal documents. And few played as important a role as Ben Franklin in the events which led to their signing.