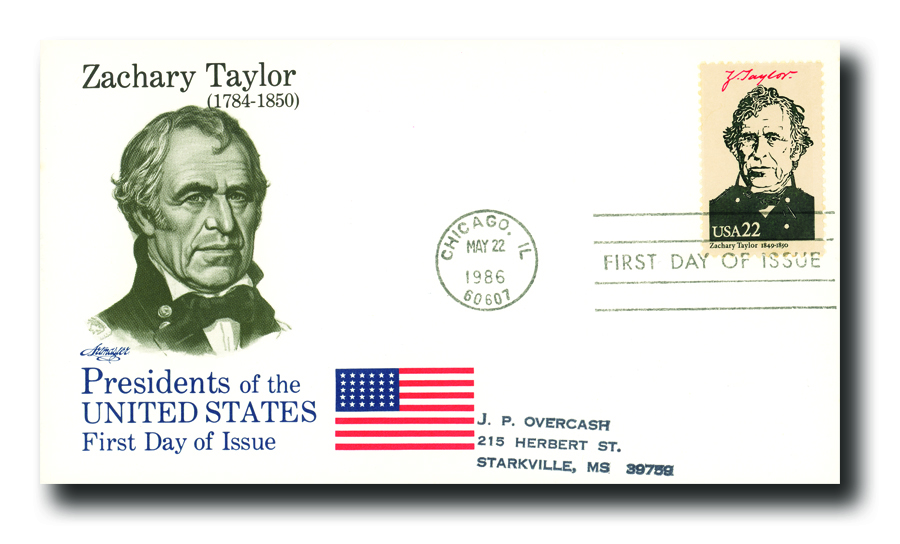

# 2217c - 1986 22c Pres. Taylor,single

Death Of President Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor was born in Montebello, Virginia, on November 24, 1784. The Taylors didn’t encourage their children’s education, preferring they concentrate on the farm. As a result, Zachary’s handwriting was poor and he was not a good student. Taylor developed a fondness for farming that would remain with him all his life. He was groomed to run the plantation. But Taylor also had been interested in the military since he was young, and he joined the local militia in 1806.

Taylor enlisted in the army after his militia unit disbanded. He first saw action during the War of 1812. American forces suffered several quick defeats at the hands of the British and their Indian allies at the outbreak of the war. This encouraged other tribes to take action. Shawnee Chief Tecumseh led a group of 600 warriors to Fort Harrison, where Taylor was in charge of a force of only 50 men – 30 of whom were ill.

The Indians approached under a white truce flag and requested a negotiation in the morning. But that night, a lone warrior snuck into the fort and set a fire that destroyed most of the food and made a wide hole in the outer wall. At the same time, the rest of the force attacked the other side of the fort, but the soldiers managed to drive off the initial attack. As the Indians besieged the fort, Taylor told his men, “Taylor never surrenders!” The garrison managed to hang on through an eight-day siege, until a relief column was able to drive off the attacking natives. Taylor resigned from the army after the war, but rejoined it a year later as a major.

Taylor went on to serve in the Black Hawk War and then the Second Seminole War, which was an effort to force a relocation of the Seminole tribe in Florida. Taylor was promoted to general after a victory on Christmas Day, 1837, at Lake Okeechobee, and was one of several high profile commanders throughout the seven-year conflict. In 1838, he was put in charge of the campaign – mostly a series of raids and skirmishes around long stretches of uneasy peace. Taylor’s strategy was based on building a network of forts to slowly drive the Seminoles out of the disputed territory. After serving two years as military commander – longer than any other U.S. commander in the conflict – he received a transfer in 1840.

After the Republic of Texas won its independence from Mexico in 1836, it sought to join the United States. The annexation of Texas was delayed because the U.S. and Mexico disagreed over the southern border of the Territory. Taylor was sent to set up a camp at the Rio Grande to defend the American claim. He raised a force of 4,000 volunteers and established a military base. Several months later, Taylor crossed the river into territory that undisputedly belonged to Mexico and scored victories at the Battles of Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma. He went on to attack Monterrey, negotiate a temporary peace treaty, and then capture Saltillo.

Taylor’s legend was growing in the U.S. Popular opinion for Taylor was so high that President James K. Polk feared his political aspirations, and sent General Winfield Scott to take control of the Mexican campaign. He also ordered Taylor to give Scott some of his best troops. Taylor was left with a force of a little more than 4,000 soldiers.

In the meantime, Mexican president Santa Anna led an army of nearly 20,000 troops north to fight Taylor. Taylor again faced an enemy force that was several times larger than his own – and again he won, in the Battle of Buena Vista. The victory effectively ended the fighting in northern Mexico. Taylor, meanwhile, returned home to explore his political options.

Nobody knew what Zachary Taylor’s political leanings were. He had never spoken about them publicly, and had never voted in a presidential election. He owned a large number of slaves, but opposed expansion of slavery into the West. He was a Southerner, but firmly disagreed with talk of secession. The Whig party, meanwhile, needed a strong candidate. After a series of Jacksonian Democrat Presidents (Jackson, Van Buren, Polk), the Whigs tried to revive a strategy that worked for them earlier, when they were able to get war hero Benjamin Harrison elected. Despite opposing several of the primary Whig ideals, Taylor said, “I am a Whig, but not an ultra-Whig.” Despite concerns about Taylor’s lack of commitment to Whig ideals, the party nominated him as its candidate for President.

The Whigs sent Taylor a letter offering the party’s nomination with postage due, but he didn’t read it, since he never accepted postage due letters. They sent him another one, and also sent a telegram that finally got the offer across.

Taylor faced Democrat Lewis Cass in the general election. Some Whig supporters in the North formed a third party called the Free Soil Party, and nominated former President Martin Van Buren. Taylor did not commit himself on the major issues (mostly regarding slavery), and his casual manner and military heroics gained him many admirers. The Free Soil Party pulled enough votes away from Cass that Taylor was able to win the election with a 163-127 margin in the electoral votes.

Taylor quickly confirmed Whig fears. In his Inaugural Address, he invited New Mexico and California to apply for statehood with their own preference on the slavery issue, rather than one decided by territory location. Neither state was expected to be in favor of slavery, and the Southern-dominated Whigs wanted the process controlled through negotiations for Territory status, where it could be decided by groups outside the areas in question.

Taylor also affirmed his plans to use presidential vetoes only for Constitutional issues, and not to block legislation for policy reasons. When he later noted that he would not use tariffs for anything other than increasing revenue (as opposed to protective reasons), this represented a near-complete rejection of Whig core values.

As talks of secession began to rise, particularly in South Carolina, Taylor responded strongly. He said he would personally lead the Army against anyone rising in rebellion “he would hang…with less reluctance than he had hanged deserters and spies in Mexico.” This shocked politicians on both sides, and Henry Clay of Kentucky and Daniel Webster of Massachusetts forged an agreement that came to be called the “Compromise of 1850.” Taylor was opposed to the Compromise, and even though it quickly passed Congress, he was expected to veto it.

Taylor attended a celebration on July 4th, 1850. He wore a thick coat on a hot day, and snacked on ice milk and cherries to cool off. He complained of sickness and cramps, and his condition grew worse until he died five days later, on July 9, 1850. The exact causes of his death are still unknown, and there have been rumors he was poisoned. Many historians agree the most likely cause was typhoid fever, possibly brought on by the heat of the day with the cold snack shocking his system. Vice President Millard Fillmore succeeded Taylor and became the 13th U.S. President. Taylor had served only 16 months of his term.

Death Of President Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor was born in Montebello, Virginia, on November 24, 1784. The Taylors didn’t encourage their children’s education, preferring they concentrate on the farm. As a result, Zachary’s handwriting was poor and he was not a good student. Taylor developed a fondness for farming that would remain with him all his life. He was groomed to run the plantation. But Taylor also had been interested in the military since he was young, and he joined the local militia in 1806.

Taylor enlisted in the army after his militia unit disbanded. He first saw action during the War of 1812. American forces suffered several quick defeats at the hands of the British and their Indian allies at the outbreak of the war. This encouraged other tribes to take action. Shawnee Chief Tecumseh led a group of 600 warriors to Fort Harrison, where Taylor was in charge of a force of only 50 men – 30 of whom were ill.

The Indians approached under a white truce flag and requested a negotiation in the morning. But that night, a lone warrior snuck into the fort and set a fire that destroyed most of the food and made a wide hole in the outer wall. At the same time, the rest of the force attacked the other side of the fort, but the soldiers managed to drive off the initial attack. As the Indians besieged the fort, Taylor told his men, “Taylor never surrenders!” The garrison managed to hang on through an eight-day siege, until a relief column was able to drive off the attacking natives. Taylor resigned from the army after the war, but rejoined it a year later as a major.

Taylor went on to serve in the Black Hawk War and then the Second Seminole War, which was an effort to force a relocation of the Seminole tribe in Florida. Taylor was promoted to general after a victory on Christmas Day, 1837, at Lake Okeechobee, and was one of several high profile commanders throughout the seven-year conflict. In 1838, he was put in charge of the campaign – mostly a series of raids and skirmishes around long stretches of uneasy peace. Taylor’s strategy was based on building a network of forts to slowly drive the Seminoles out of the disputed territory. After serving two years as military commander – longer than any other U.S. commander in the conflict – he received a transfer in 1840.

After the Republic of Texas won its independence from Mexico in 1836, it sought to join the United States. The annexation of Texas was delayed because the U.S. and Mexico disagreed over the southern border of the Territory. Taylor was sent to set up a camp at the Rio Grande to defend the American claim. He raised a force of 4,000 volunteers and established a military base. Several months later, Taylor crossed the river into territory that undisputedly belonged to Mexico and scored victories at the Battles of Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma. He went on to attack Monterrey, negotiate a temporary peace treaty, and then capture Saltillo.

Taylor’s legend was growing in the U.S. Popular opinion for Taylor was so high that President James K. Polk feared his political aspirations, and sent General Winfield Scott to take control of the Mexican campaign. He also ordered Taylor to give Scott some of his best troops. Taylor was left with a force of a little more than 4,000 soldiers.

In the meantime, Mexican president Santa Anna led an army of nearly 20,000 troops north to fight Taylor. Taylor again faced an enemy force that was several times larger than his own – and again he won, in the Battle of Buena Vista. The victory effectively ended the fighting in northern Mexico. Taylor, meanwhile, returned home to explore his political options.

Nobody knew what Zachary Taylor’s political leanings were. He had never spoken about them publicly, and had never voted in a presidential election. He owned a large number of slaves, but opposed expansion of slavery into the West. He was a Southerner, but firmly disagreed with talk of secession. The Whig party, meanwhile, needed a strong candidate. After a series of Jacksonian Democrat Presidents (Jackson, Van Buren, Polk), the Whigs tried to revive a strategy that worked for them earlier, when they were able to get war hero Benjamin Harrison elected. Despite opposing several of the primary Whig ideals, Taylor said, “I am a Whig, but not an ultra-Whig.” Despite concerns about Taylor’s lack of commitment to Whig ideals, the party nominated him as its candidate for President.

The Whigs sent Taylor a letter offering the party’s nomination with postage due, but he didn’t read it, since he never accepted postage due letters. They sent him another one, and also sent a telegram that finally got the offer across.

Taylor faced Democrat Lewis Cass in the general election. Some Whig supporters in the North formed a third party called the Free Soil Party, and nominated former President Martin Van Buren. Taylor did not commit himself on the major issues (mostly regarding slavery), and his casual manner and military heroics gained him many admirers. The Free Soil Party pulled enough votes away from Cass that Taylor was able to win the election with a 163-127 margin in the electoral votes.

Taylor quickly confirmed Whig fears. In his Inaugural Address, he invited New Mexico and California to apply for statehood with their own preference on the slavery issue, rather than one decided by territory location. Neither state was expected to be in favor of slavery, and the Southern-dominated Whigs wanted the process controlled through negotiations for Territory status, where it could be decided by groups outside the areas in question.

Taylor also affirmed his plans to use presidential vetoes only for Constitutional issues, and not to block legislation for policy reasons. When he later noted that he would not use tariffs for anything other than increasing revenue (as opposed to protective reasons), this represented a near-complete rejection of Whig core values.

As talks of secession began to rise, particularly in South Carolina, Taylor responded strongly. He said he would personally lead the Army against anyone rising in rebellion “he would hang…with less reluctance than he had hanged deserters and spies in Mexico.” This shocked politicians on both sides, and Henry Clay of Kentucky and Daniel Webster of Massachusetts forged an agreement that came to be called the “Compromise of 1850.” Taylor was opposed to the Compromise, and even though it quickly passed Congress, he was expected to veto it.

Taylor attended a celebration on July 4th, 1850. He wore a thick coat on a hot day, and snacked on ice milk and cherries to cool off. He complained of sickness and cramps, and his condition grew worse until he died five days later, on July 9, 1850. The exact causes of his death are still unknown, and there have been rumors he was poisoned. Many historians agree the most likely cause was typhoid fever, possibly brought on by the heat of the day with the cold snack shocking his system. Vice President Millard Fillmore succeeded Taylor and became the 13th U.S. President. Taylor had served only 16 months of his term.