# 2436 - 1989 25c Traditional Mail Delivery: Biplane

U.S. #2436

1989 25¢ Bi-plane

Traditional Mail Delivery

- Issued for the 20th Universal Postal Union, first in the US in 92 years

- Stamp design pictures a Jenny bi-plane

- Also issued as part of World Stamp Expo ’89

Stamp Category: Commemorative

Set: Traditional Mail Delivery

Value: 25¢, first-class mail rate

First Day of Issue: November 19, 1989

First Day City: Washington, D.C.

Quantity Issued: 40,956,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Lithographed & engraved

Format: Panes of 40 in sheets of 160

Perforations: 11

Why the stamp was issued: The block of four Traditional Mail Delivery stamps was issued to commemorate the United States’ hosting of 20th Universal Postal Union Congress. It was the first time the US hosted the UPU in 92 years. The stamp issue, and the congress, also coincided with World Stamp Expo ’89. A souvenir sheet bearing the same designs (#2438) was issued nine days later.

About the stamp design: First-time stamp artist Mark Hess was hired to illustrate the Classic Mail Transportation Block. He worked from a variety of sources, including photos from the National Philatelic Collection at the Smithsonian. After completing his first drafts, he shared them with the curator of the National Philatelic Collection, who offered several suggestions to help make his designs more accurate.

Hess’ original sketch of the Curtiss Jenny showed two open cockpits. But he corrected it to show that one of the cockpits had been replaced with a mail compartment.

Special design details: Some of the transportation methods in this block had appeared on stamps before. The Jenny had appeared on America’s first Airmails (#C1-3), and the Jenny and the stagecoach were included in a block of four stamps honoring the 200th anniversary of America’s independent postal service (#1572-75). Plus, the automobile is very similar to the one pictured on a 1912 15¢ Parcel Post stamp (#Q7).

First Day City: The First Day Ceremony for the Classic Mail Transportation block was held the Washington Convention Center in Washington, DC, as part of the 20th Universal Postal Union Congress and World Stamp Expo ’89. Each day of the expo had a theme, and this day’s theme was Old West Day. An actor portraying Buffalo Bill Cody participated in the ceremony.

Unusual fact about this stamp: Errors with the dark blue engraving (USA and 25) have been found.

About the Traditional Mail Delivery Stamps: Early on, USPS officials decided that the stamps honoring the UPU Congress would feature mail delivery methods. Initially, art director Richard Sheaff mocked up a block of nine stamps showing delivery methods from around the world. After significant discussion, they decided that the stamps would only picture US mail delivery methods. They also decided to create two separate blocks depicting past delivery methods and future delivery methods (block of four – #C122-25 and souvenir sheet – #C126).

The other stamps in the set picture:

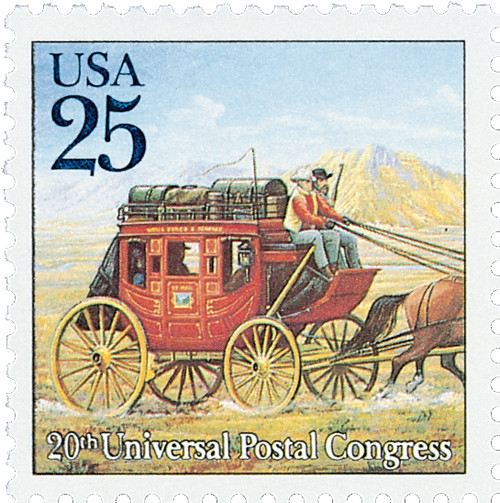

Stagecoach (#2434) – Hess’ stagecoach image underwent the fewest changes. It depicts a Concord coach, named for the city in New Hampshire where they were made.

Steamboat (#2435) – The design that required the most work was the ship stamp. Initially, Hess pictured a naval ship off-shore with a rowboat collecting mail for delivery to the ship. The image had some inaccuracies, and it was ultimately decided that a steamboat on an inland river better represented that form of mail delivery. The steamboat on which the stamp image was based is the 19th century packet Chesapeake. The stamp also shows a man with a handcart bringing mail to the boat, which he had seen on one the Smithsonian pictures.

Early automobile (#2437) – Hess based his image of an automobile delivering mail on a photo from the USPS archives. It pictures a 1906 Columbia automobile on the streets of Baltimore.

About the Universal Postal Union: On October 9, 1874, some 22 nations met in Bern, Switzerland to form the General Postal Union (later renamed the Universal Postal Union or UPU).

In 1863, Abraham Lincoln’s Postmaster General Montgomery Blair suggested an international conference be held to discuss common postal problems. A conference was held in Paris, and fifteen nations attempted to establish guidelines for an international postal service. Until this time, mail had been regulated by a number of different agreements that were binding only to signing members.

Although Blair did not intend to create a permanent organization, another conference was held 11 years later in Bern, Switzerland. On October 9, 1874, twenty-two nations, comprising the International Postal congress, drafted and signed the Bern Treaty, which established the General Postal Union. The basic ideals were that there should be a uniform rate to mail a letter anywhere in the world, that domestic and international mail should be treated equally, and that each country should keep all money collected for international postage. It also made sending international mail easier in another important way. Previously, people had to attach a stamp from each country their mail would pass through. This no longer was necessary.

Under this treaty, member nations, including parts of Europe, Britain, and the United States, standardized postal rates and units of weight. They also set forth procedures for transporting ordinary mail. Ordinary mail included letters, postcards, and small packages. Separate rules govern the transportation of items, such as parcel post, newspapers, magazines, and money orders.

Under this agreement, known as the International Postal Convention, a simpler accounting system was devised as well. Previously, countries could vary the international rate. Any mail traveling across a country’s border was charged this rate. In addition, many countries charged a one-cent surtax for mail being transported by sea for more than 300 miles.

Using the basic idea that every letter generates a reply, the Convention allowed each country to keep the postage it collected on international mail. However, that country would then reimburse other members for transporting mail across their borders. The benefits to member nations included lower postal rates, better service, and a more efficient accounting system.

At the 1878 conference, the name was changed to the Universal Postal Union. It wasn’t until the 1880s that the organization became truly universal. By the 1890s, nearly every nation had become a member.

In 1898, the Universal Postal Union standardized the colors of certain stamps in order to make international mailing easier and more efficient. They proposed that member nations use the same colors for stamps of the same value. In order to conform to the UPU’s regulations, the 1¢, 2¢, and 5¢ stamps underwent color changes. Later that same year, the 4¢, 6¢, 10¢, and 15¢ stamps were changed to avoid confusion with current issues printed in similar colors.

In 1947, the UPU became a specialized agency of the United Nations with its headquarters is located in Berne, the capital of Switzerland. The UPU holds conventions every five years. Today, it continues to organize and improve postal service throughout the world with 190 member states. It’s the oldest international organization existing and claims to be the only one that really works.

History this stamp represents: On May 15, 1918, America’s airmail service began when two Curtiss Jenny’s departed New York and Washington, DC.

As a new form of transportation, early flight was a pioneering effort that suffered from a near-complete lack of precedent. More than a decade after Orville Wright’s historic 1903 flight, aircraft mechanics, instructors, and flight schools were still virtually non-existent. But as World War I engulfed the globe, many were soon convinced that air supremacy was the key to victory.

Many great innovations and improvements to aircraft followed, and by 1918, the US had a fleet of Curtiss Jenny’s that could fly at a top speed of 80 miles per hour with a range of 175 miles and could maintain an altitude of 11,000 feet. Meanwhile, the possibility of airmail delivery had been debated and dismissed for nearly a decade. So it came as a surprise to many when Postmaster General Burleson suddenly announced that service would begin between New York City, Philadelphia, and Washington, DC. The year was 1918 and the world was at war. Critics argued that every available resource was needed to win the war – including planes and pilots.

However, Burleson brokered a deal with the War Department on March 1, 1918, that satisfied a very important military issue. Experienced pilots were scarce. America’s most seasoned pilots were serving overseas, leaving few opportunities for training new recruits. Under the new arrangement, the Postal Department would handle their traditional tasks and the military would provide the planes and pilots. Americans would have a rapid system of mail transportation, and military pilots would receive badly needed flight training.

Major Reuben H. Fleet, an Army executive officer in charge of planning instruction, was placed in charge of making the necessary arrangements. Fleet received his assignment on May 6 – just days before the scheduled May 15th flight.

The plan for the first regularly scheduled flights in US aviation history seems simple by today’s standards. One plane was to depart New York and fly south at the same time a second plane flew north from Washington, DC. The planes were to meet in Philadelphia to exchange mailbags and refuel before returning home.

On the morning of May 15, 1918, a crowd of several hundred gathered at Washington’s Polo Grounds to witness history being made. Lt. George Boyle climbed inside the Jenny with bags containing 5,500 letters destined to fly on the first airmail route in US history.

As President Woodrow Wilson looked on with a crowd of dignitaries, mechanics tried to start Boyle’s plane. The propeller turned but the engine wouldn’t start. After four attempts, mechanics checked the gas tank and realized the plane was out of fuel. Furthermore, there was no gas on the field, so mechanics quickly siphoned fuel out of nearby planes. Boyle flew off for his journey to Philadelphia at 11:46 a.m. – 45 minutes late and barely clearing nearby trees.

Hours later, officials would learn that Boyle had flown in the wrong direction and crashed his plane. Instructed to follow the train tracks north, Boyle had become disoriented and used a southeastern branch of the track as his guide. Although Lt. Boyle escaped injury, his plane was lying upside down in a field near Otto Praeger’s country home, much as it appeared on the legendary inverted stamps! The mailbags aboard Boyle’s plane were quietly brought back to Washington, DC, and flown to Philadelphia and New York City the following day.

Meanwhile, Lt. Webb had left New York and arrived safely in Philadelphia. His mailbags were transferred to the waiting plane of Lt. Edgerton, who arrived in Washington, DC, at 2:20 p.m. After two weeks of intense preparation and high drama, America’s first airmail service was established. In the months that followed, pioneering aviators expanded airmail service, flying by the seat of their pants over the treacherous Allegheny Mountains to Chicago and eventually the west coast.

U.S. #2436

1989 25¢ Bi-plane

Traditional Mail Delivery

- Issued for the 20th Universal Postal Union, first in the US in 92 years

- Stamp design pictures a Jenny bi-plane

- Also issued as part of World Stamp Expo ’89

Stamp Category: Commemorative

Set: Traditional Mail Delivery

Value: 25¢, first-class mail rate

First Day of Issue: November 19, 1989

First Day City: Washington, D.C.

Quantity Issued: 40,956,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Lithographed & engraved

Format: Panes of 40 in sheets of 160

Perforations: 11

Why the stamp was issued: The block of four Traditional Mail Delivery stamps was issued to commemorate the United States’ hosting of 20th Universal Postal Union Congress. It was the first time the US hosted the UPU in 92 years. The stamp issue, and the congress, also coincided with World Stamp Expo ’89. A souvenir sheet bearing the same designs (#2438) was issued nine days later.

About the stamp design: First-time stamp artist Mark Hess was hired to illustrate the Classic Mail Transportation Block. He worked from a variety of sources, including photos from the National Philatelic Collection at the Smithsonian. After completing his first drafts, he shared them with the curator of the National Philatelic Collection, who offered several suggestions to help make his designs more accurate.

Hess’ original sketch of the Curtiss Jenny showed two open cockpits. But he corrected it to show that one of the cockpits had been replaced with a mail compartment.

Special design details: Some of the transportation methods in this block had appeared on stamps before. The Jenny had appeared on America’s first Airmails (#C1-3), and the Jenny and the stagecoach were included in a block of four stamps honoring the 200th anniversary of America’s independent postal service (#1572-75). Plus, the automobile is very similar to the one pictured on a 1912 15¢ Parcel Post stamp (#Q7).

First Day City: The First Day Ceremony for the Classic Mail Transportation block was held the Washington Convention Center in Washington, DC, as part of the 20th Universal Postal Union Congress and World Stamp Expo ’89. Each day of the expo had a theme, and this day’s theme was Old West Day. An actor portraying Buffalo Bill Cody participated in the ceremony.

Unusual fact about this stamp: Errors with the dark blue engraving (USA and 25) have been found.

About the Traditional Mail Delivery Stamps: Early on, USPS officials decided that the stamps honoring the UPU Congress would feature mail delivery methods. Initially, art director Richard Sheaff mocked up a block of nine stamps showing delivery methods from around the world. After significant discussion, they decided that the stamps would only picture US mail delivery methods. They also decided to create two separate blocks depicting past delivery methods and future delivery methods (block of four – #C122-25 and souvenir sheet – #C126).

The other stamps in the set picture:

Stagecoach (#2434) – Hess’ stagecoach image underwent the fewest changes. It depicts a Concord coach, named for the city in New Hampshire where they were made.

Steamboat (#2435) – The design that required the most work was the ship stamp. Initially, Hess pictured a naval ship off-shore with a rowboat collecting mail for delivery to the ship. The image had some inaccuracies, and it was ultimately decided that a steamboat on an inland river better represented that form of mail delivery. The steamboat on which the stamp image was based is the 19th century packet Chesapeake. The stamp also shows a man with a handcart bringing mail to the boat, which he had seen on one the Smithsonian pictures.

Early automobile (#2437) – Hess based his image of an automobile delivering mail on a photo from the USPS archives. It pictures a 1906 Columbia automobile on the streets of Baltimore.

About the Universal Postal Union: On October 9, 1874, some 22 nations met in Bern, Switzerland to form the General Postal Union (later renamed the Universal Postal Union or UPU).

In 1863, Abraham Lincoln’s Postmaster General Montgomery Blair suggested an international conference be held to discuss common postal problems. A conference was held in Paris, and fifteen nations attempted to establish guidelines for an international postal service. Until this time, mail had been regulated by a number of different agreements that were binding only to signing members.

Although Blair did not intend to create a permanent organization, another conference was held 11 years later in Bern, Switzerland. On October 9, 1874, twenty-two nations, comprising the International Postal congress, drafted and signed the Bern Treaty, which established the General Postal Union. The basic ideals were that there should be a uniform rate to mail a letter anywhere in the world, that domestic and international mail should be treated equally, and that each country should keep all money collected for international postage. It also made sending international mail easier in another important way. Previously, people had to attach a stamp from each country their mail would pass through. This no longer was necessary.

Under this treaty, member nations, including parts of Europe, Britain, and the United States, standardized postal rates and units of weight. They also set forth procedures for transporting ordinary mail. Ordinary mail included letters, postcards, and small packages. Separate rules govern the transportation of items, such as parcel post, newspapers, magazines, and money orders.

Under this agreement, known as the International Postal Convention, a simpler accounting system was devised as well. Previously, countries could vary the international rate. Any mail traveling across a country’s border was charged this rate. In addition, many countries charged a one-cent surtax for mail being transported by sea for more than 300 miles.

Using the basic idea that every letter generates a reply, the Convention allowed each country to keep the postage it collected on international mail. However, that country would then reimburse other members for transporting mail across their borders. The benefits to member nations included lower postal rates, better service, and a more efficient accounting system.

At the 1878 conference, the name was changed to the Universal Postal Union. It wasn’t until the 1880s that the organization became truly universal. By the 1890s, nearly every nation had become a member.

In 1898, the Universal Postal Union standardized the colors of certain stamps in order to make international mailing easier and more efficient. They proposed that member nations use the same colors for stamps of the same value. In order to conform to the UPU’s regulations, the 1¢, 2¢, and 5¢ stamps underwent color changes. Later that same year, the 4¢, 6¢, 10¢, and 15¢ stamps were changed to avoid confusion with current issues printed in similar colors.

In 1947, the UPU became a specialized agency of the United Nations with its headquarters is located in Berne, the capital of Switzerland. The UPU holds conventions every five years. Today, it continues to organize and improve postal service throughout the world with 190 member states. It’s the oldest international organization existing and claims to be the only one that really works.

History this stamp represents: On May 15, 1918, America’s airmail service began when two Curtiss Jenny’s departed New York and Washington, DC.

As a new form of transportation, early flight was a pioneering effort that suffered from a near-complete lack of precedent. More than a decade after Orville Wright’s historic 1903 flight, aircraft mechanics, instructors, and flight schools were still virtually non-existent. But as World War I engulfed the globe, many were soon convinced that air supremacy was the key to victory.

Many great innovations and improvements to aircraft followed, and by 1918, the US had a fleet of Curtiss Jenny’s that could fly at a top speed of 80 miles per hour with a range of 175 miles and could maintain an altitude of 11,000 feet. Meanwhile, the possibility of airmail delivery had been debated and dismissed for nearly a decade. So it came as a surprise to many when Postmaster General Burleson suddenly announced that service would begin between New York City, Philadelphia, and Washington, DC. The year was 1918 and the world was at war. Critics argued that every available resource was needed to win the war – including planes and pilots.

However, Burleson brokered a deal with the War Department on March 1, 1918, that satisfied a very important military issue. Experienced pilots were scarce. America’s most seasoned pilots were serving overseas, leaving few opportunities for training new recruits. Under the new arrangement, the Postal Department would handle their traditional tasks and the military would provide the planes and pilots. Americans would have a rapid system of mail transportation, and military pilots would receive badly needed flight training.

Major Reuben H. Fleet, an Army executive officer in charge of planning instruction, was placed in charge of making the necessary arrangements. Fleet received his assignment on May 6 – just days before the scheduled May 15th flight.

The plan for the first regularly scheduled flights in US aviation history seems simple by today’s standards. One plane was to depart New York and fly south at the same time a second plane flew north from Washington, DC. The planes were to meet in Philadelphia to exchange mailbags and refuel before returning home.

On the morning of May 15, 1918, a crowd of several hundred gathered at Washington’s Polo Grounds to witness history being made. Lt. George Boyle climbed inside the Jenny with bags containing 5,500 letters destined to fly on the first airmail route in US history.

As President Woodrow Wilson looked on with a crowd of dignitaries, mechanics tried to start Boyle’s plane. The propeller turned but the engine wouldn’t start. After four attempts, mechanics checked the gas tank and realized the plane was out of fuel. Furthermore, there was no gas on the field, so mechanics quickly siphoned fuel out of nearby planes. Boyle flew off for his journey to Philadelphia at 11:46 a.m. – 45 minutes late and barely clearing nearby trees.

Hours later, officials would learn that Boyle had flown in the wrong direction and crashed his plane. Instructed to follow the train tracks north, Boyle had become disoriented and used a southeastern branch of the track as his guide. Although Lt. Boyle escaped injury, his plane was lying upside down in a field near Otto Praeger’s country home, much as it appeared on the legendary inverted stamps! The mailbags aboard Boyle’s plane were quietly brought back to Washington, DC, and flown to Philadelphia and New York City the following day.

Meanwhile, Lt. Webb had left New York and arrived safely in Philadelphia. His mailbags were transferred to the waiting plane of Lt. Edgerton, who arrived in Washington, DC, at 2:20 p.m. After two weeks of intense preparation and high drama, America’s first airmail service was established. In the months that followed, pioneering aviators expanded airmail service, flying by the seat of their pants over the treacherous Allegheny Mountains to Chicago and eventually the west coast.