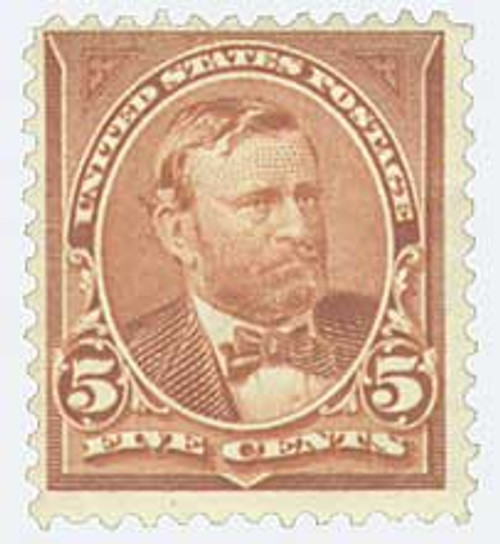

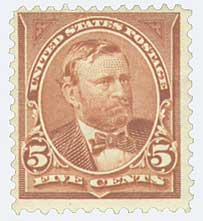

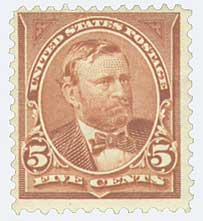

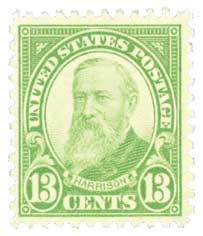

# 270 - 1895 5c Grant, chocolate, double line watermark

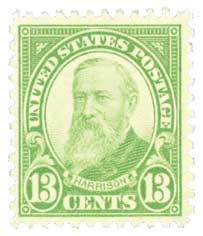

1895 5¢ Grant

Issue Quantity: 123,775,455

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Watermark: Double line USPS

Perforation: 12

Color: Chocolate

Although a relatively small number of U.S. #270 stamps were produced, 24 plates were required for the print run. That’s because impurities in the ink wore the plates quickly.

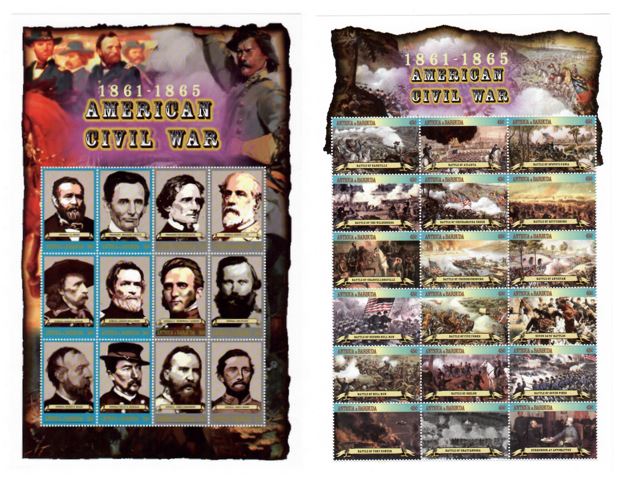

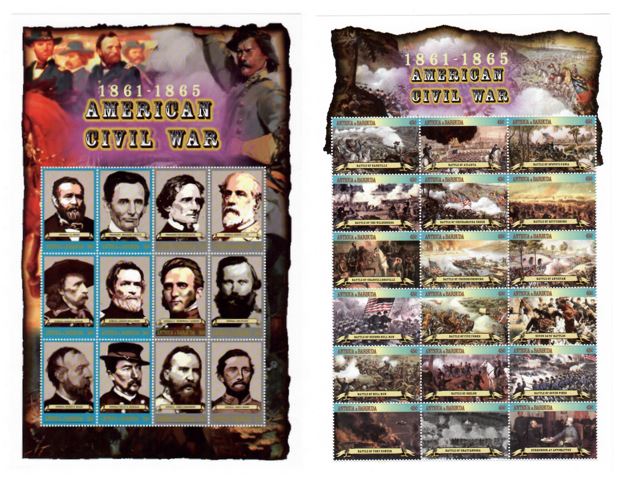

Battle Of Nashville

Confederate General John Bell Hood was defeated at Franklin, and his Army of Tennessee suffered great losses. In spite of being greatly outnumbered, he pressed on to the well-fortified stronghold of Nashville. On December 2, 1864, the Rebels approached the city from the south. Hood knew his forces were not strong enough to attack the Union, so the Southern army put up four miles of defenses and waited for the enemy to attack.

Major General John Schofield and his victorious Army of Ohio had arrived from Franklin the day before Hood’s men. They joined the Union forces that were already reinforcing the lines of defense around Nashville. The works stretched for seven miles in a semicircle, protecting the city on the south and west. The Cumberland River formed a natural defense around the rest. The troops inside numbered about 55,000 men. Major General George Thomas was in command.

Thomas began preparing for an assault on Hood. His cavalry needed fresh horses and better arms. The commander knew they would be facing Lieutenant General Nathan Bedford Forrest, one of the best cavalry leaders on either side of the war.

Leaders in Washington were getting impatient with the delay. They were concerned Hood would move away from Nashville and invade Kentucky or Ohio. Commander Ulysses S. Grant ordered a replacement to go to Nashville if Thomas did not begin his attack by December 13. In fact, Grant was on his way to take over himself when he heard Thomas had finally made his move.

In the early hours of December 15, Thomas sent two brigades toward the right of the Confederate line in the hopes of drawing Southern troops away from the main attack. These men had the least experience of any of the Union soldiers in Nashville and included three regiments of US Colored Troops, who had previously guarded the railroads. After overtaking the skirmish line, they faced heavy fire and retreated. The brigades reformed and held the Confederates for the rest of the day. Though they were successful in engaging forces on the right, Hood did not send additional support as Thomas predicted.

While those brigades were in the midst of combat, a large movement was set in motion on the west side of the Rebel line. A corps of cavalry led the way and swept the opponents’ cavalry from the area. Two corps of infantry followed the Union horsemen, the second held in reserve. At about 2:30 pm, the North began attacking a series of five redoubts (temporary forts) that guarded the Confederate left. Redoubts number two through five fell in quick succession.

While that portion of the Union force was attacking to the west, another corps made a frontal assault. They had prepared to meet the enemy on Montgomery Hill, but the Confederates had retreated to a stronger position. The oncoming army met only a skirmish line on the hill and then advanced to the main army. Soldiers coming from both directions captured the last redoubt, and the Confederates retreated to a new line to the south. Fighting ended as both sides prepared for another conflict the following day.

The new Confederate line was shorter than the previous one and the flanks were protected by Peach Orchard Hill to the east and Compton’s Hill on the west. During the night and early morning, additional defense works were hastily built. Thomas would once again attack the Rebels from multiple directions, starting on the enemy’s right. Peach Orchard Hill became the focus of the first assault beginning at about 3:00 in the afternoon. This time, Southern artillery and musket fire stopped the advance. The 13th US Colored Troops, however, did not turn back. They captured the Confederate parapet at the cost of about 40 percent of their unit. Unlike the day before, Hood shifted his forces to reinforce his right flank. As a result, the line guarding Compton’s Hill was depleted.

Meanwhile, the Union cavalry was making its way to the Confederate rear around the left flank. Southern forces were stretched even farther to protect the rear. Schofield had been instructed to lead the frontal attack, but he delayed. Division commander John McArthur sent word to Thomas he would begin an attack in five minutes unless he was directed otherwise. McArthur’s brigades charged forward over Compton’s Hill in three separate columns, overwhelming the Confederates. The Rebels retreated to the south towards Franklin, with the Union cavalry in pursuit.

The Army of Tennessee continued south, with the enemy close behind. When it reached Alabama, the Union gave up their chase. Hood then led his army to Tupelo, Mississippi, where he resigned his command. He had begun his campaign in Tennessee with approximately 38,000 men. On January 13, Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard reported there were fewer than 15,000 remaining.

1895 5¢ Grant

Issue Quantity: 123,775,455

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Watermark: Double line USPS

Perforation: 12

Color: Chocolate

Although a relatively small number of U.S. #270 stamps were produced, 24 plates were required for the print run. That’s because impurities in the ink wore the plates quickly.

Battle Of Nashville

Confederate General John Bell Hood was defeated at Franklin, and his Army of Tennessee suffered great losses. In spite of being greatly outnumbered, he pressed on to the well-fortified stronghold of Nashville. On December 2, 1864, the Rebels approached the city from the south. Hood knew his forces were not strong enough to attack the Union, so the Southern army put up four miles of defenses and waited for the enemy to attack.

Major General John Schofield and his victorious Army of Ohio had arrived from Franklin the day before Hood’s men. They joined the Union forces that were already reinforcing the lines of defense around Nashville. The works stretched for seven miles in a semicircle, protecting the city on the south and west. The Cumberland River formed a natural defense around the rest. The troops inside numbered about 55,000 men. Major General George Thomas was in command.

Thomas began preparing for an assault on Hood. His cavalry needed fresh horses and better arms. The commander knew they would be facing Lieutenant General Nathan Bedford Forrest, one of the best cavalry leaders on either side of the war.

Leaders in Washington were getting impatient with the delay. They were concerned Hood would move away from Nashville and invade Kentucky or Ohio. Commander Ulysses S. Grant ordered a replacement to go to Nashville if Thomas did not begin his attack by December 13. In fact, Grant was on his way to take over himself when he heard Thomas had finally made his move.

In the early hours of December 15, Thomas sent two brigades toward the right of the Confederate line in the hopes of drawing Southern troops away from the main attack. These men had the least experience of any of the Union soldiers in Nashville and included three regiments of US Colored Troops, who had previously guarded the railroads. After overtaking the skirmish line, they faced heavy fire and retreated. The brigades reformed and held the Confederates for the rest of the day. Though they were successful in engaging forces on the right, Hood did not send additional support as Thomas predicted.

While those brigades were in the midst of combat, a large movement was set in motion on the west side of the Rebel line. A corps of cavalry led the way and swept the opponents’ cavalry from the area. Two corps of infantry followed the Union horsemen, the second held in reserve. At about 2:30 pm, the North began attacking a series of five redoubts (temporary forts) that guarded the Confederate left. Redoubts number two through five fell in quick succession.

While that portion of the Union force was attacking to the west, another corps made a frontal assault. They had prepared to meet the enemy on Montgomery Hill, but the Confederates had retreated to a stronger position. The oncoming army met only a skirmish line on the hill and then advanced to the main army. Soldiers coming from both directions captured the last redoubt, and the Confederates retreated to a new line to the south. Fighting ended as both sides prepared for another conflict the following day.

The new Confederate line was shorter than the previous one and the flanks were protected by Peach Orchard Hill to the east and Compton’s Hill on the west. During the night and early morning, additional defense works were hastily built. Thomas would once again attack the Rebels from multiple directions, starting on the enemy’s right. Peach Orchard Hill became the focus of the first assault beginning at about 3:00 in the afternoon. This time, Southern artillery and musket fire stopped the advance. The 13th US Colored Troops, however, did not turn back. They captured the Confederate parapet at the cost of about 40 percent of their unit. Unlike the day before, Hood shifted his forces to reinforce his right flank. As a result, the line guarding Compton’s Hill was depleted.

Meanwhile, the Union cavalry was making its way to the Confederate rear around the left flank. Southern forces were stretched even farther to protect the rear. Schofield had been instructed to lead the frontal attack, but he delayed. Division commander John McArthur sent word to Thomas he would begin an attack in five minutes unless he was directed otherwise. McArthur’s brigades charged forward over Compton’s Hill in three separate columns, overwhelming the Confederates. The Rebels retreated to the south towards Franklin, with the Union cavalry in pursuit.

The Army of Tennessee continued south, with the enemy close behind. When it reached Alabama, the Union gave up their chase. Hood then led his army to Tupelo, Mississippi, where he resigned his command. He had begun his campaign in Tennessee with approximately 38,000 men. On January 13, Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard reported there were fewer than 15,000 remaining.