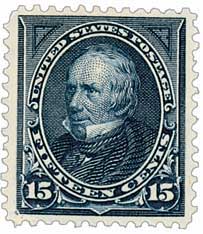

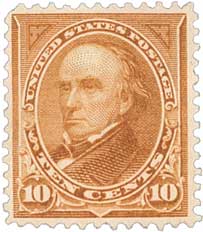

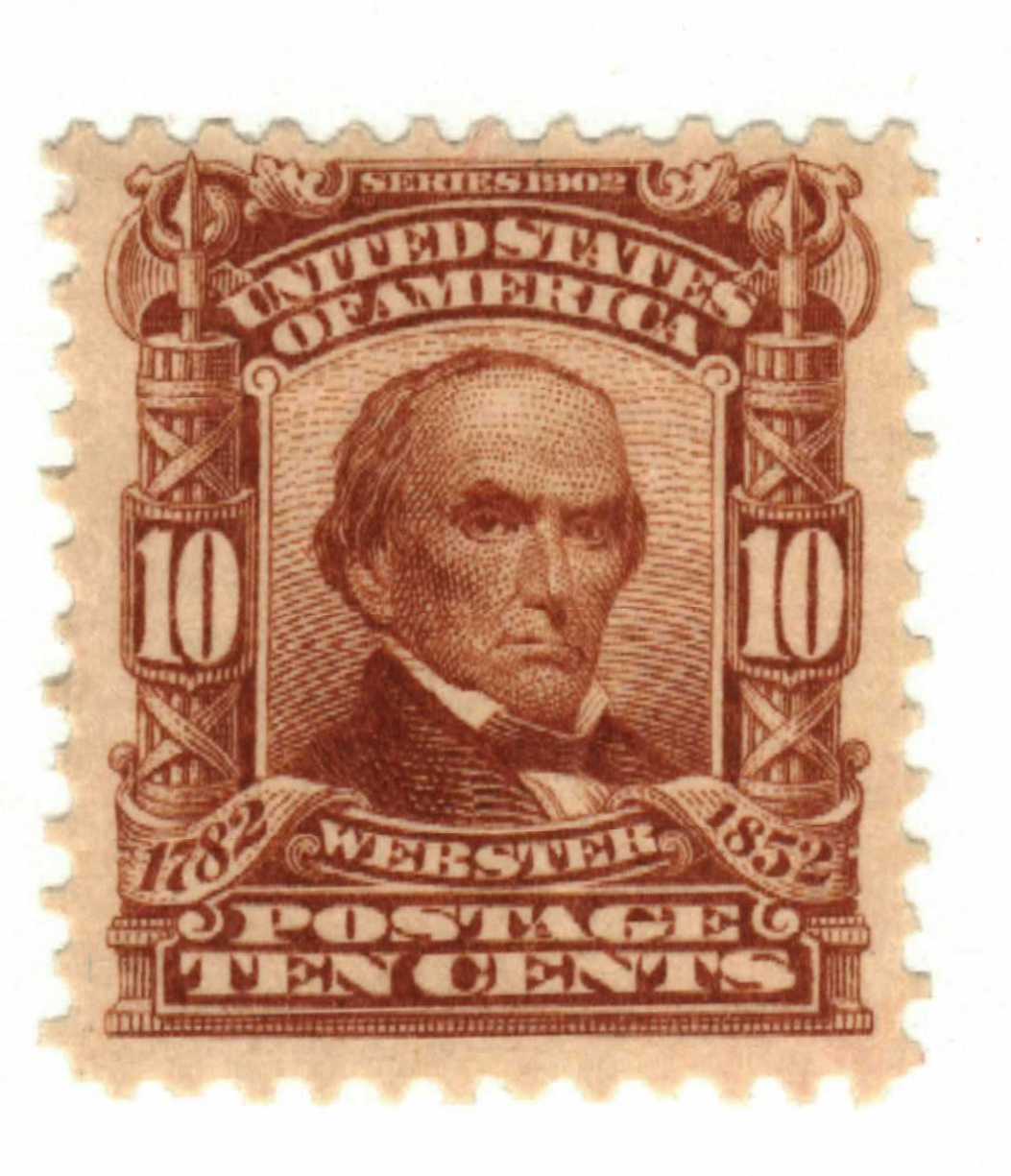

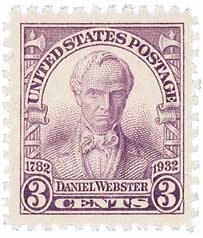

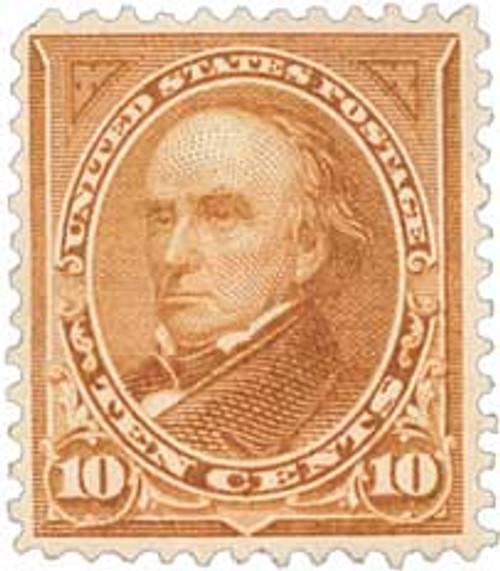

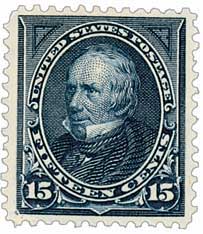

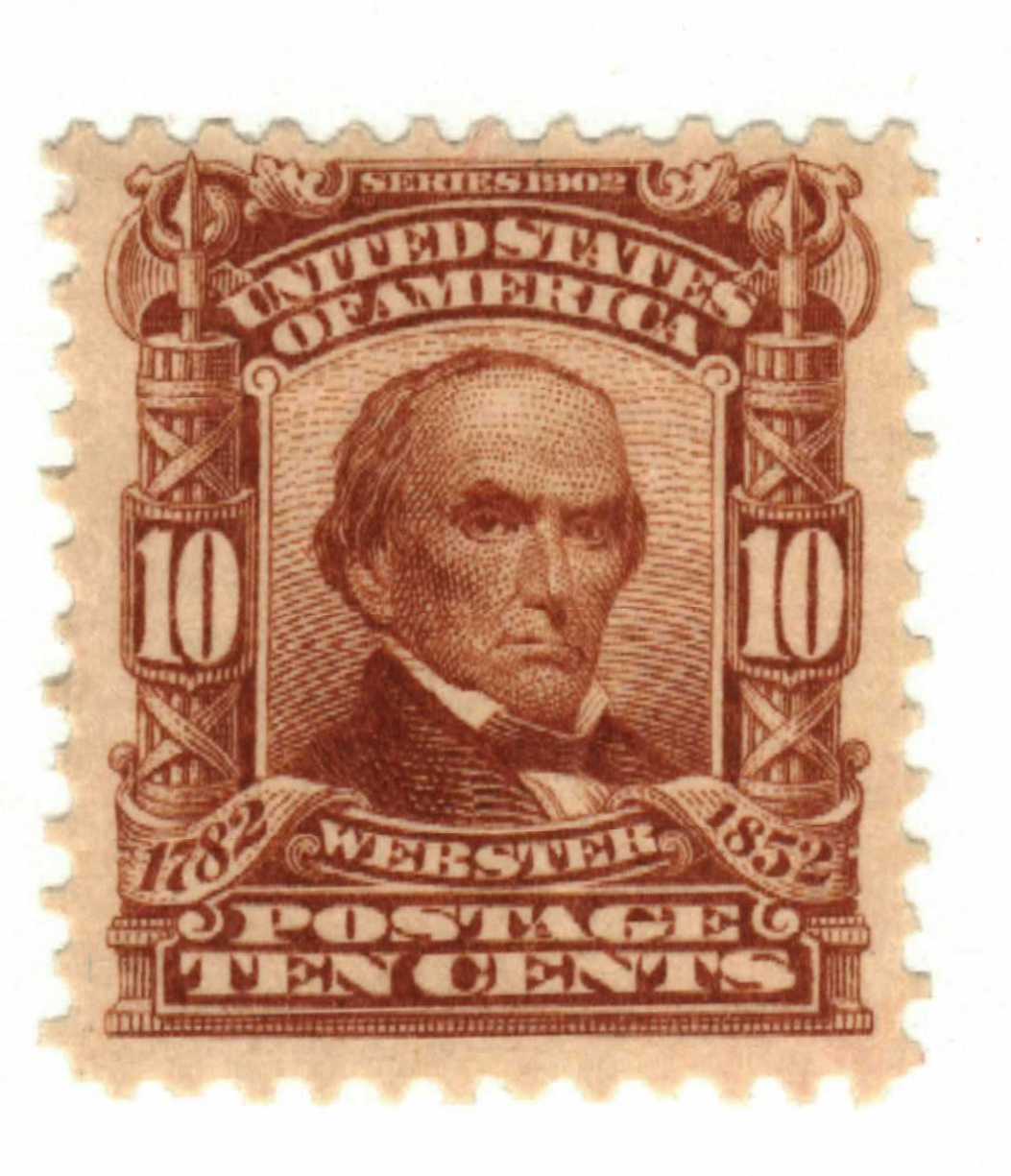

# 283 - 1897-1903 10c Webster, orange brown

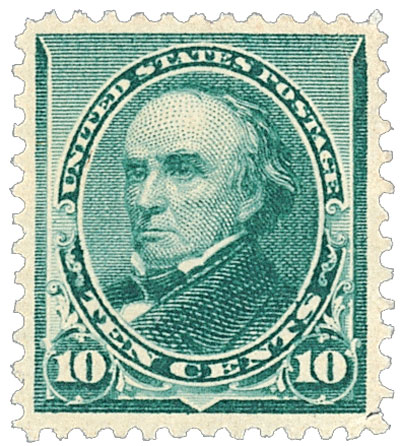

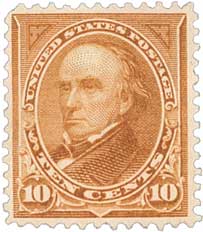

Series of 1898-99 10¢ Webster

Type II

Universal Postal Union Colors

Issue Quantity: 65,000,000 (estimate)

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Watermark: Double line USPS

Perforation: 12

Color: Orange brown

The Type I (U.S. #282C) and Type II (U.S. #283) stamps are most easily distinguished by color. U.S. #282C is brown, while U.S. #283 is yellow or orange brown.

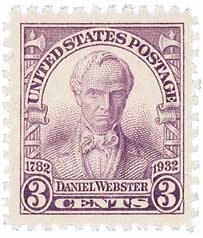

On March 7, 1850, Massachusetts Senator Daniel Webster delivered one of his most famous speeches, the “Seventh of March” speech. It expressed his support for the Compromise of 1850 that would help avert a Civil War but proved disastrous for his Senate career. As talks of secession began to rise, particularly in South Carolina, President Zachary Taylor responded strongly. He said he would personally lead the Army against anyone rising in rebellion – “he would hang…with less reluctance than he had hanged deserters and spies in Mexico.” This shocked politicians on both sides, and Henry Clay of Kentucky forged an agreement that came to be called the “Compromise of 1850.” The proposed compromise was as controversial as the slavery debate itself. The bill proposed the organization of Utah and New Mexico, leaving the decision on whether to be a slave or free territories to the citizens of those regions. The bill would also make California a free state and prohibit slave auctions in the District of Columbia. Additionally, the bill would introduce a new fugitive slave law. This ordered runaway slaves found anywhere in the United States be returned to their owners if a board of commissioners declared them fugitives. The bill would allow authorities to arrest Blacks and return them to slave territory, whether they were slaves or not. President Zachary Taylor refused to take a side on the issue, while Vice President Fillmore urged him to pass the bill. Debate over the compromise raged. On March 7, 1850, Webster addressed the Senate in a three-and-a-half-hour speech in support of the compromise. He hoped his words might unite his fellow Senators. He argued that it was pointless to fight about continuing slavery where it was already instituted. He also said they shouldn’t need to discuss extending slavery to the dry lands in the southwest, where plantations wouldn’t survive. Webster’s speech was quickly sent to newspapers around the country via telegraph. Across most of the nation his speech was well-received. But back home in New England he was widely criticized and accused of cutting a deal with Southern leaders to support the bill in exchange for their support in his presidential campaign. Webster had lost the support of his state and resigned from the Senate that July. This was shortly after President Taylor had died. Fillmore quickly assumed the presidency and accepted the resignations of Taylor’s entire Cabinet. Fillmore immediately replaced them with men he expected to support the compromise and focused all his energy into getting it passed. He made Webster his secretary of State. However, the task would not be easy, as Clay introduced a modified version of the bill and the pro- and anti-slavery forces in Congress battled over every line. Worn down by the constant fighting, Clay left the capital and Stephen Douglas came in as his replacement. Douglas broke the Compromise down into five smaller bills, getting each passed one by one. As a result, Texas received $10 million for settling its border dispute with New Mexico, California was admitted as a free state, New Mexico and Utah became territories, slave trading was made illegal in Washington, DC, and the Fugitive Slave Law passed with little quarrel in the Senate or House. Fillmore saw the passage of all five bills as a great triumph in inter-party cooperation, keeping America united. Although the agreement delayed the Civil War for a decade, it highlighted a deep divide.Webster’s “Seventh of March” Speech

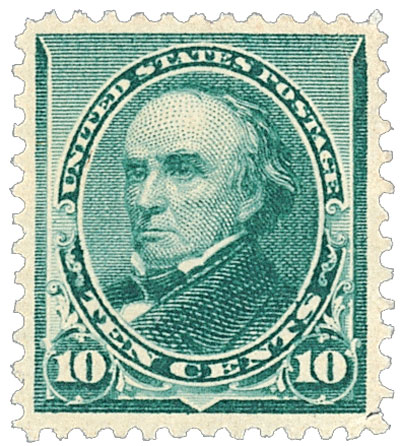

Series of 1898-99 10¢ Webster

Type II

Universal Postal Union Colors

Issue Quantity: 65,000,000 (estimate)

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Watermark: Double line USPS

Perforation: 12

Color: Orange brown

The Type I (U.S. #282C) and Type II (U.S. #283) stamps are most easily distinguished by color. U.S. #282C is brown, while U.S. #283 is yellow or orange brown.

On March 7, 1850, Massachusetts Senator Daniel Webster delivered one of his most famous speeches, the “Seventh of March” speech. It expressed his support for the Compromise of 1850 that would help avert a Civil War but proved disastrous for his Senate career. As talks of secession began to rise, particularly in South Carolina, President Zachary Taylor responded strongly. He said he would personally lead the Army against anyone rising in rebellion – “he would hang…with less reluctance than he had hanged deserters and spies in Mexico.” This shocked politicians on both sides, and Henry Clay of Kentucky forged an agreement that came to be called the “Compromise of 1850.” The proposed compromise was as controversial as the slavery debate itself. The bill proposed the organization of Utah and New Mexico, leaving the decision on whether to be a slave or free territories to the citizens of those regions. The bill would also make California a free state and prohibit slave auctions in the District of Columbia. Additionally, the bill would introduce a new fugitive slave law. This ordered runaway slaves found anywhere in the United States be returned to their owners if a board of commissioners declared them fugitives. The bill would allow authorities to arrest Blacks and return them to slave territory, whether they were slaves or not. President Zachary Taylor refused to take a side on the issue, while Vice President Fillmore urged him to pass the bill. Debate over the compromise raged. On March 7, 1850, Webster addressed the Senate in a three-and-a-half-hour speech in support of the compromise. He hoped his words might unite his fellow Senators. He argued that it was pointless to fight about continuing slavery where it was already instituted. He also said they shouldn’t need to discuss extending slavery to the dry lands in the southwest, where plantations wouldn’t survive. Webster’s speech was quickly sent to newspapers around the country via telegraph. Across most of the nation his speech was well-received. But back home in New England he was widely criticized and accused of cutting a deal with Southern leaders to support the bill in exchange for their support in his presidential campaign. Webster had lost the support of his state and resigned from the Senate that July. This was shortly after President Taylor had died. Fillmore quickly assumed the presidency and accepted the resignations of Taylor’s entire Cabinet. Fillmore immediately replaced them with men he expected to support the compromise and focused all his energy into getting it passed. He made Webster his secretary of State. However, the task would not be easy, as Clay introduced a modified version of the bill and the pro- and anti-slavery forces in Congress battled over every line. Worn down by the constant fighting, Clay left the capital and Stephen Douglas came in as his replacement. Douglas broke the Compromise down into five smaller bills, getting each passed one by one. As a result, Texas received $10 million for settling its border dispute with New Mexico, California was admitted as a free state, New Mexico and Utah became territories, slave trading was made illegal in Washington, DC, and the Fugitive Slave Law passed with little quarrel in the Senate or House. Fillmore saw the passage of all five bills as a great triumph in inter-party cooperation, keeping America united. Although the agreement delayed the Civil War for a decade, it highlighted a deep divide.Webster’s “Seventh of March” Speech