# 2869o - 1994 29c Legends of the West: Wild Bill Hickock

U.S. #2869o

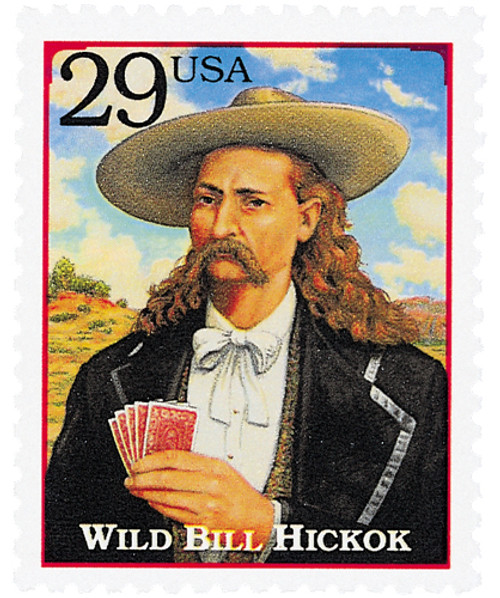

1994 29¢ Wild Bill Hickok

Legends of the West

- From the corrected version of the famed Legends of the West error sheet

- First sheet in the Classic Collection Series

Stamp Category: Commemorative

Set: Legends of the West

Value: 29¢, rate for first-class mail

First Day of Issue: October 18, 1994

First Day Cities: Tucson, Arizona; Lawton, Oklahoma; Laramie, Wyoming

Quantity Issued: 19,282,800

Printed by: Stamp Venturers

Printing Method: Photogravure

Format: Panes of 20 in sheets of 120

Perforations: 10.2 x 10.1

Why the stamp was issued: The Legends of the West sheet was the first issue in the Classic Collection Series. It was developed from an idea to honor “Western Americana.”

About the stamp design: Stamp artist Mark Hess spent nearly two years working on the Legends of the West stamps. Wild Bill Hickok’s portrait was based on a photo taken around 1873. While he was originally painted holding a six-shooter, Hess eventually changed it to a handful of cards, depicting his well-known habit of gambling.

Special design details: This stamp comes from the famed Legends of the West sheet, which made headlines due to two mistakes made by the United States Postal Service and led to a string of events without precedent in the history of US stamp collecting.

One of the people to be featured on the sheet was black rodeo star Bill Pickett. After the stamps were announced, but not officially issued, a radio reporter phoned Frank Phillips Jr., great-grandson of Bill Pickett, and asked him about the stamp. Phillips went to his local post office, looked at the design and recognized it as Ben Pickett – Bill’s brother and business associate. The stamp pictured the wrong man! That was the first mistake.

Phillips complained to the Postal Service and Postmaster General Marvin Runyon issued an order to recall and destroy the error stamps. Runyon also ordered new revised stamps be created – these are the corrected Legends of the West stamps – #2869.

But before the recall, 186 error sheets were sold by postal workers – before the official “first day of issue.” This was the second mistake. These error sheets were being resold for sums ranging from $3,000 to $15,000 each!

Several weeks later the US Postal Service announced that 150,000 error sheets would be sold at face value by means of a mail order lottery. This unprecedented move was made with the permission of Frank Phillips Jr. so the Post Office could recover its printing cost and not lose money. Sales were limited to one per household. The remaining stamps were destroyed.

About the printing process: In order to include the text on the back of the Legends of the West stamps, it had to be printed under the gum, so that it would still be visible if a stamp was soaked off an envelope. Because people would need to lick the stamps, the ink had to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration as non-toxic. The printer also used an extra-fine 300-line screen, which resulted in some of the highest-quality gravure stamp printings in recent years.

First Day Cities: The Laramie, Wyoming First Day ceremony was held at the University of Wyoming. The Tucson, Arizona ceremony was held at the Old Tucson Studios, where the High Chaparral TV series and several Western movies had been filmed. The Lawton, Oklahoma ceremony was held at Fort Sill, where Geronimo was buried.

About the Legends of the West: The Legends of the West sheet was ultimately born out of a discussion to issue a stamp to honor the 100th anniversary of Ellis Island in 1992. That plan was abandoned, but was Ellis Island was featured on a postal card in the Historic Preservation Series (#UX165). Talks then pivoted to a stamp honoring “Western Americana.” Stamp artist Mark Hess was tasked with producing four semi-jumbo stamp images capturing the colorful and graphic look of old Wild West show posters. The Citizens Stamp Advisory Committee (CSAC) discussed Hess’ images and decided to expand on the idea and honor 16 significant men and women that played major roles in the expansion of the West. At one point, they considered outlaws such as Butch Cassidy, Billy the Kid, and Jesse James, but ultimately decided to “come down on the side of right and justice.” The sheet of 20 had a decorative header and descriptive text was included on the back of each stamp.

The Legends of the West stamp designs were also adapted to postal cards, #UX178-97.

History the stamp represents:

James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok was born on May 27, 1837, in Homer, Illinois (present-day Troy Grove). A soldier, scout, lawman, gambler, showman, expert marksman, and gunfighter, he was a legend in his own time.

Hickok was the fourth of six children and it’s been said that his family’s home was a station on the Underground Railroad. Hickok was recognized as an excellent marksman from a young age. He left home after a shootout in 1855, settling in Leavenworth, Kansas Territory. There he joined the Free State Army, a group of antislavery fighters. He went to serve as one of the first four constables of Monticello Township in Kansas and worked for the Russell, Majors and Waddell freight company, the parent company of the Pony Express.

Hickok went by several names in his early years. Sometimes he used his father’s name, William. Sometimes his last name was reported as Haycock. He was also nicknamed “Duck Bill” due to his long nose and protruding lips. Another nickname he once held was “Shanghai Bill,” for his tall and skinny build. In 1861, he grew a mustache and began calling himself “Wild Bill.”

During the Civil war, Hickok was a scout and spy for the Union Army. On July 21, 1865, he participated in what’s considered America’s first Western showdown. Hickok had previously lost a watch of great sentimental value to Davis Tutt in a poker game. He asked Tutt not to wear it in public, but he did anyway, and tensions escalated to the shootout. Tutt missed entirely, but Hickok struck Tutt in the chest, killing him. A warrant was issued for Hickok’s arrest, and he stood trial. By the law of the West, the jury believed Hickok was right to shoot Tutt and found him not guilty. When Hickok’s story was later retold in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, he became a legend in his own time.

In 1865, Hickok was recommended for deputy federal marshal of Fort Riley, Kansas. At the same time, he also served as a scout for General George A. Custer’s cavalry in the Indian Wars. That same year he also hired a group of Native Americans and cowboys to travel to Niagara Falls for his own Wild West show – The Daring Buffalo Chasers of the Plains. However, the show made little money and was a failure.

In 1869, the harassed citizens of Ellis County, Kansas, elected Hickok sheriff. Spending much of his time in Hays City, he tamed the wild frontier town. In 1871, he moved on to Abilene, Kansas, where he served as the town’s marshal. While there, he engaged in a shootout with saloon owner Phil Coe. During the fight, Hickok briefly saw someone running toward him and quickly shot and killed them. He had accidentally shot a special deputy marshal that was running to help him. Hickok was relieved of his duties after that and never participated in another gunfight, haunted by what he’d done.

After that, Hickok joined Buffalo Bill Cody’s Scouts of the Plains show, but he didn’t enjoy acting and left after a few months. In 1876, he was diagnosed with glaucoma and ophthalmia, which severely affected his marksmanship. Despite this, Hickok’s fame made him a target for anyone looking to kill him for a reputation. In 1876, he moved to the gold mining town of Deadwood hoping to strike it rich. It was there he was shot and killed by Jack McCall while playing cards in a saloon on August 2, 1876. Hickok fell to the floor, still clutching a pair of aces and a pair of eights, known ever since as the “deadman’s hand.”

U.S. #2869o

1994 29¢ Wild Bill Hickok

Legends of the West

- From the corrected version of the famed Legends of the West error sheet

- First sheet in the Classic Collection Series

Stamp Category: Commemorative

Set: Legends of the West

Value: 29¢, rate for first-class mail

First Day of Issue: October 18, 1994

First Day Cities: Tucson, Arizona; Lawton, Oklahoma; Laramie, Wyoming

Quantity Issued: 19,282,800

Printed by: Stamp Venturers

Printing Method: Photogravure

Format: Panes of 20 in sheets of 120

Perforations: 10.2 x 10.1

Why the stamp was issued: The Legends of the West sheet was the first issue in the Classic Collection Series. It was developed from an idea to honor “Western Americana.”

About the stamp design: Stamp artist Mark Hess spent nearly two years working on the Legends of the West stamps. Wild Bill Hickok’s portrait was based on a photo taken around 1873. While he was originally painted holding a six-shooter, Hess eventually changed it to a handful of cards, depicting his well-known habit of gambling.

Special design details: This stamp comes from the famed Legends of the West sheet, which made headlines due to two mistakes made by the United States Postal Service and led to a string of events without precedent in the history of US stamp collecting.

One of the people to be featured on the sheet was black rodeo star Bill Pickett. After the stamps were announced, but not officially issued, a radio reporter phoned Frank Phillips Jr., great-grandson of Bill Pickett, and asked him about the stamp. Phillips went to his local post office, looked at the design and recognized it as Ben Pickett – Bill’s brother and business associate. The stamp pictured the wrong man! That was the first mistake.

Phillips complained to the Postal Service and Postmaster General Marvin Runyon issued an order to recall and destroy the error stamps. Runyon also ordered new revised stamps be created – these are the corrected Legends of the West stamps – #2869.

But before the recall, 186 error sheets were sold by postal workers – before the official “first day of issue.” This was the second mistake. These error sheets were being resold for sums ranging from $3,000 to $15,000 each!

Several weeks later the US Postal Service announced that 150,000 error sheets would be sold at face value by means of a mail order lottery. This unprecedented move was made with the permission of Frank Phillips Jr. so the Post Office could recover its printing cost and not lose money. Sales were limited to one per household. The remaining stamps were destroyed.

About the printing process: In order to include the text on the back of the Legends of the West stamps, it had to be printed under the gum, so that it would still be visible if a stamp was soaked off an envelope. Because people would need to lick the stamps, the ink had to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration as non-toxic. The printer also used an extra-fine 300-line screen, which resulted in some of the highest-quality gravure stamp printings in recent years.

First Day Cities: The Laramie, Wyoming First Day ceremony was held at the University of Wyoming. The Tucson, Arizona ceremony was held at the Old Tucson Studios, where the High Chaparral TV series and several Western movies had been filmed. The Lawton, Oklahoma ceremony was held at Fort Sill, where Geronimo was buried.

About the Legends of the West: The Legends of the West sheet was ultimately born out of a discussion to issue a stamp to honor the 100th anniversary of Ellis Island in 1992. That plan was abandoned, but was Ellis Island was featured on a postal card in the Historic Preservation Series (#UX165). Talks then pivoted to a stamp honoring “Western Americana.” Stamp artist Mark Hess was tasked with producing four semi-jumbo stamp images capturing the colorful and graphic look of old Wild West show posters. The Citizens Stamp Advisory Committee (CSAC) discussed Hess’ images and decided to expand on the idea and honor 16 significant men and women that played major roles in the expansion of the West. At one point, they considered outlaws such as Butch Cassidy, Billy the Kid, and Jesse James, but ultimately decided to “come down on the side of right and justice.” The sheet of 20 had a decorative header and descriptive text was included on the back of each stamp.

The Legends of the West stamp designs were also adapted to postal cards, #UX178-97.

History the stamp represents:

James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok was born on May 27, 1837, in Homer, Illinois (present-day Troy Grove). A soldier, scout, lawman, gambler, showman, expert marksman, and gunfighter, he was a legend in his own time.

Hickok was the fourth of six children and it’s been said that his family’s home was a station on the Underground Railroad. Hickok was recognized as an excellent marksman from a young age. He left home after a shootout in 1855, settling in Leavenworth, Kansas Territory. There he joined the Free State Army, a group of antislavery fighters. He went to serve as one of the first four constables of Monticello Township in Kansas and worked for the Russell, Majors and Waddell freight company, the parent company of the Pony Express.

Hickok went by several names in his early years. Sometimes he used his father’s name, William. Sometimes his last name was reported as Haycock. He was also nicknamed “Duck Bill” due to his long nose and protruding lips. Another nickname he once held was “Shanghai Bill,” for his tall and skinny build. In 1861, he grew a mustache and began calling himself “Wild Bill.”

During the Civil war, Hickok was a scout and spy for the Union Army. On July 21, 1865, he participated in what’s considered America’s first Western showdown. Hickok had previously lost a watch of great sentimental value to Davis Tutt in a poker game. He asked Tutt not to wear it in public, but he did anyway, and tensions escalated to the shootout. Tutt missed entirely, but Hickok struck Tutt in the chest, killing him. A warrant was issued for Hickok’s arrest, and he stood trial. By the law of the West, the jury believed Hickok was right to shoot Tutt and found him not guilty. When Hickok’s story was later retold in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, he became a legend in his own time.

In 1865, Hickok was recommended for deputy federal marshal of Fort Riley, Kansas. At the same time, he also served as a scout for General George A. Custer’s cavalry in the Indian Wars. That same year he also hired a group of Native Americans and cowboys to travel to Niagara Falls for his own Wild West show – The Daring Buffalo Chasers of the Plains. However, the show made little money and was a failure.

In 1869, the harassed citizens of Ellis County, Kansas, elected Hickok sheriff. Spending much of his time in Hays City, he tamed the wild frontier town. In 1871, he moved on to Abilene, Kansas, where he served as the town’s marshal. While there, he engaged in a shootout with saloon owner Phil Coe. During the fight, Hickok briefly saw someone running toward him and quickly shot and killed them. He had accidentally shot a special deputy marshal that was running to help him. Hickok was relieved of his duties after that and never participated in another gunfight, haunted by what he’d done.

After that, Hickok joined Buffalo Bill Cody’s Scouts of the Plains show, but he didn’t enjoy acting and left after a few months. In 1876, he was diagnosed with glaucoma and ophthalmia, which severely affected his marksmanship. Despite this, Hickok’s fame made him a target for anyone looking to kill him for a reputation. In 1876, he moved to the gold mining town of Deadwood hoping to strike it rich. It was there he was shot and killed by Jack McCall while playing cards in a saloon on August 2, 1876. Hickok fell to the floor, still clutching a pair of aces and a pair of eights, known ever since as the “deadman’s hand.”