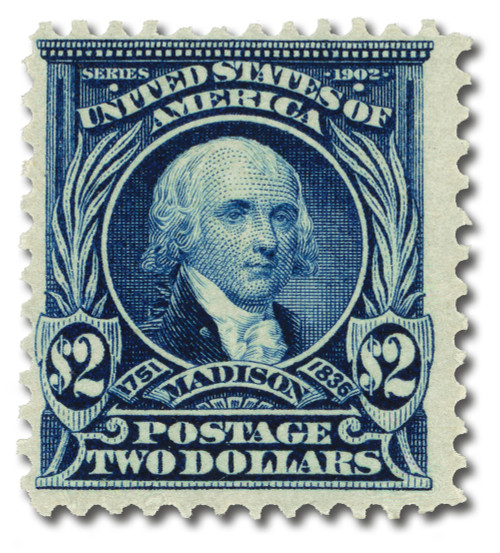

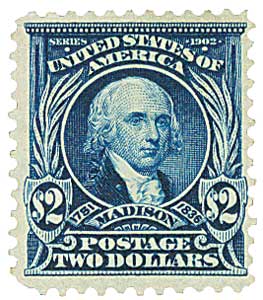

# 312 - 1903 $2 Madison, dark blue

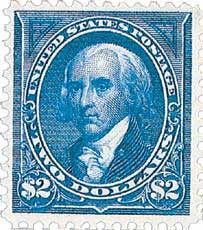

Series of 1902-03 $2 Madison

Quantity issued: 37,872

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Method: Flat plate

Watermark: Double line

Perforation: 12

Color: Dark blue

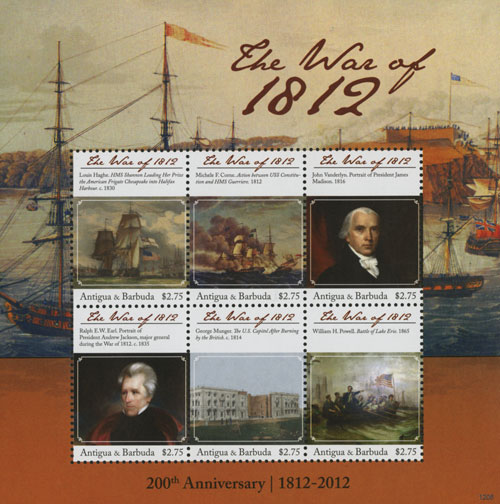

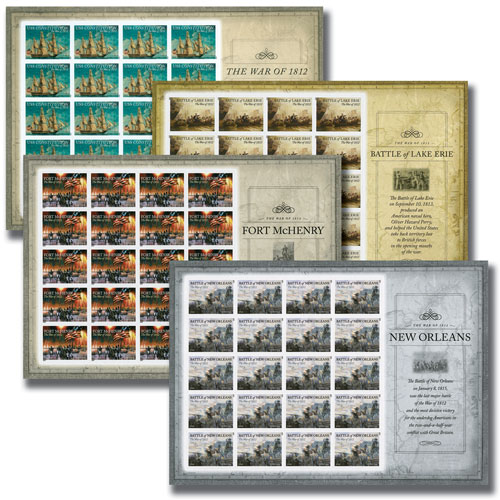

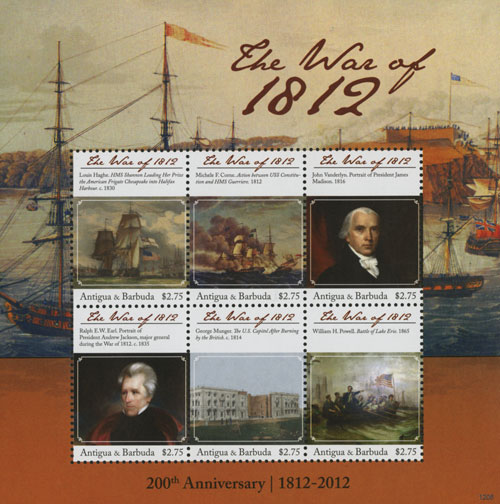

America Declares War On Great Britain

Just 29 years after gaining independence, the United States took on the greatest naval power in the world by declaring war on June 18, 1812, in what would become America’s “Second War of Independence.”

Great Britain was embroiled in a lengthy and bitter war with France as the 19th century dawned. Both countries blocked the United States from trading with the other, hoping to deprive their enemy of badly needed supplies.

In 1807, Great Britain passed an act requiring all neutral countries to obtain a license from its officials before trading with France or its colonies. At the same time, American sailors were being kidnapped off U.S. merchant ships and forced to serve on British vessels. In a ten-year period before the hostilities began, approximately 10,000 U.S. sailors were impressed into service in this manner.

Britain and France were also guilty of plundering U.S. merchant ships for supplies to wage war against each other. President Thomas Jefferson enacted the Embargo Act of 1807 in response, but the restrictions hurt American trade more than it did Britain or France.

Congress repealed the act in 1809, replacing it with a bill sought to encourage either of the nations to ease sanctions against the U.S. In the event one of the nations removed the trade restrictions, the bill would have allowed for the U.S. to block trade with the other. Napoleon indicated France would stop the restrictions, prompting President James Madison to stop all commerce with Britain.

In addition to the trade embargo and matter of impressment, Britain was seen as an ally of Native Americans opposed to America’s expansion in the West. Many members of Congress, led by John Calhoun and Henry Clay, called for war against Britain.

In November of 1811, William H. Harrison led troops into Indiana Territory to destroy a confederacy of Native Americans led by Tecumseh. As territorial governor, Harrison had encouraged new settlers to the territory in the hopes statehood would be granted. Tecumseh’s confederacy harassed settlers and other Native American leaders who negotiated with them.

Harrison’s troops defeated Tecumseh’s at the Battle of Tippecanoe. The defeat confirmed Tecumseh’s belief that he needed support from Britain to stop the settlers from encroaching farther into Northwest Territory. During this time, hawkish members of Congress were pressuring President Madison to strike against Britain. On June 18, 1812, Madison signed the declaration of war on Great Britain, Ireland, and their territories, notably Canada.

In 1812, Canada was a British colony. Canada’s shared border with the U.S. made it an efficient way to strike a blow to Britain. In what became a series of follies, William Hull, an Indian agent and territorial governor of Michigan, took inexperienced troops across the border into Upper Canada (modern Ontario). There they faced well-trained forces led by Sir Isaac Brock, whose men had been preparing for attack. Tecumseh and his warriors had joined the British, hoping to fend off the Americans.

The armies met on August 16, 1812, with the U.S. suffering a humiliating defeat. Brock and Tecumseh’s men turned the Americans away and pursued them across the border, where Hull surrendered Detroit without a fight.

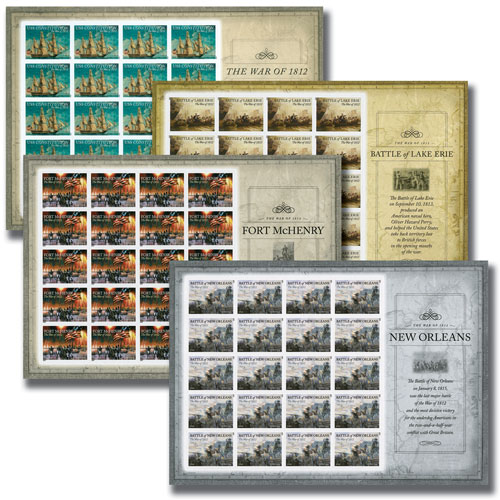

Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry won a strategic victory at the Battle of Lake Erie in 1813, putting the Northwest Territory under U.S. control again. This enabled William Harrison to retake Detroit in the Battle of the Thames, which ended with the death of Tecumseh. The U.S. Navy was also able to defeat the Royal Navy in several key battles.

Britain defeated France in 1814, allowing it to focus all resources and manpower solely on war with the United States. With a fresh supply of troops, the British were able to move up Chesapeake Bay and attack Washington, D.C., on August 24, 1814. Several government buildings were burned, including the Capitol and White House.

A few weeks later, the British Navy bombarded Baltimore’s Fort McHenry for 25 hours. As the new day dawned, the defenders hoisted an enormous American flag to show the fort had withstood the attack. The sight of the flag inspired Francis Scott Key to write “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Great Britain’s land troops, who had simultaneously moved to strike Baltimore during the naval onslaught, were also repulsed and their leader killed. Defeated, the British withdrew and prepared to invade New Orleans.

Although the nation’s military prepared for more battle, the defeat at Baltimore convinced British commissioners to meet with U.S. representatives in the Flemish city of Ghent to negotiate for peace. The U.S. agreed to end its demands to stop impressment, while the British promised to discontinue the creation of an Indian state in the Northwest and leave the Canadian border unchanged. The Treaty of Ghent was signed on December 24, 1814.

Unaware peace had been agreed upon, British troops mounted an assault on the vital port city of New Orleans. Led by Major General Andrew Jackson, American troops prevented the invasion and saved both the city and the vast territory the U.S. had gained with the Louisiana Purchase.

Although the War of 1812 failed to achieve its original goals, victory at the Battle of New Orleans increased morale in the U.S. The young nation had defeated the world’s mightiest empire, with the crowning victory over the illustrious Royal Navy. The “Era of Good Feelings” was ushered in as Americans felt a sense of unity and pride. In turn, this mood of self-confidence and purpose helped fuel the period of American expansionism that would define most of the 19th century.

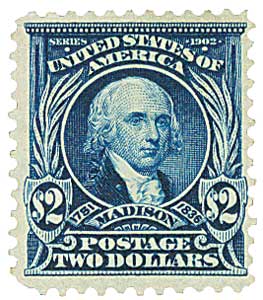

Series of 1902-03 $2 Madison

Quantity issued: 37,872

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Method: Flat plate

Watermark: Double line

Perforation: 12

Color: Dark blue

America Declares War On Great Britain

Just 29 years after gaining independence, the United States took on the greatest naval power in the world by declaring war on June 18, 1812, in what would become America’s “Second War of Independence.”

Great Britain was embroiled in a lengthy and bitter war with France as the 19th century dawned. Both countries blocked the United States from trading with the other, hoping to deprive their enemy of badly needed supplies.

In 1807, Great Britain passed an act requiring all neutral countries to obtain a license from its officials before trading with France or its colonies. At the same time, American sailors were being kidnapped off U.S. merchant ships and forced to serve on British vessels. In a ten-year period before the hostilities began, approximately 10,000 U.S. sailors were impressed into service in this manner.

Britain and France were also guilty of plundering U.S. merchant ships for supplies to wage war against each other. President Thomas Jefferson enacted the Embargo Act of 1807 in response, but the restrictions hurt American trade more than it did Britain or France.

Congress repealed the act in 1809, replacing it with a bill sought to encourage either of the nations to ease sanctions against the U.S. In the event one of the nations removed the trade restrictions, the bill would have allowed for the U.S. to block trade with the other. Napoleon indicated France would stop the restrictions, prompting President James Madison to stop all commerce with Britain.

In addition to the trade embargo and matter of impressment, Britain was seen as an ally of Native Americans opposed to America’s expansion in the West. Many members of Congress, led by John Calhoun and Henry Clay, called for war against Britain.

In November of 1811, William H. Harrison led troops into Indiana Territory to destroy a confederacy of Native Americans led by Tecumseh. As territorial governor, Harrison had encouraged new settlers to the territory in the hopes statehood would be granted. Tecumseh’s confederacy harassed settlers and other Native American leaders who negotiated with them.

Harrison’s troops defeated Tecumseh’s at the Battle of Tippecanoe. The defeat confirmed Tecumseh’s belief that he needed support from Britain to stop the settlers from encroaching farther into Northwest Territory. During this time, hawkish members of Congress were pressuring President Madison to strike against Britain. On June 18, 1812, Madison signed the declaration of war on Great Britain, Ireland, and their territories, notably Canada.

In 1812, Canada was a British colony. Canada’s shared border with the U.S. made it an efficient way to strike a blow to Britain. In what became a series of follies, William Hull, an Indian agent and territorial governor of Michigan, took inexperienced troops across the border into Upper Canada (modern Ontario). There they faced well-trained forces led by Sir Isaac Brock, whose men had been preparing for attack. Tecumseh and his warriors had joined the British, hoping to fend off the Americans.

The armies met on August 16, 1812, with the U.S. suffering a humiliating defeat. Brock and Tecumseh’s men turned the Americans away and pursued them across the border, where Hull surrendered Detroit without a fight.

Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry won a strategic victory at the Battle of Lake Erie in 1813, putting the Northwest Territory under U.S. control again. This enabled William Harrison to retake Detroit in the Battle of the Thames, which ended with the death of Tecumseh. The U.S. Navy was also able to defeat the Royal Navy in several key battles.

Britain defeated France in 1814, allowing it to focus all resources and manpower solely on war with the United States. With a fresh supply of troops, the British were able to move up Chesapeake Bay and attack Washington, D.C., on August 24, 1814. Several government buildings were burned, including the Capitol and White House.

A few weeks later, the British Navy bombarded Baltimore’s Fort McHenry for 25 hours. As the new day dawned, the defenders hoisted an enormous American flag to show the fort had withstood the attack. The sight of the flag inspired Francis Scott Key to write “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Great Britain’s land troops, who had simultaneously moved to strike Baltimore during the naval onslaught, were also repulsed and their leader killed. Defeated, the British withdrew and prepared to invade New Orleans.

Although the nation’s military prepared for more battle, the defeat at Baltimore convinced British commissioners to meet with U.S. representatives in the Flemish city of Ghent to negotiate for peace. The U.S. agreed to end its demands to stop impressment, while the British promised to discontinue the creation of an Indian state in the Northwest and leave the Canadian border unchanged. The Treaty of Ghent was signed on December 24, 1814.

Unaware peace had been agreed upon, British troops mounted an assault on the vital port city of New Orleans. Led by Major General Andrew Jackson, American troops prevented the invasion and saved both the city and the vast territory the U.S. had gained with the Louisiana Purchase.

Although the War of 1812 failed to achieve its original goals, victory at the Battle of New Orleans increased morale in the U.S. The young nation had defeated the world’s mightiest empire, with the crowning victory over the illustrious Royal Navy. The “Era of Good Feelings” was ushered in as Americans felt a sense of unity and pride. In turn, this mood of self-confidence and purpose helped fuel the period of American expansionism that would define most of the 19th century.