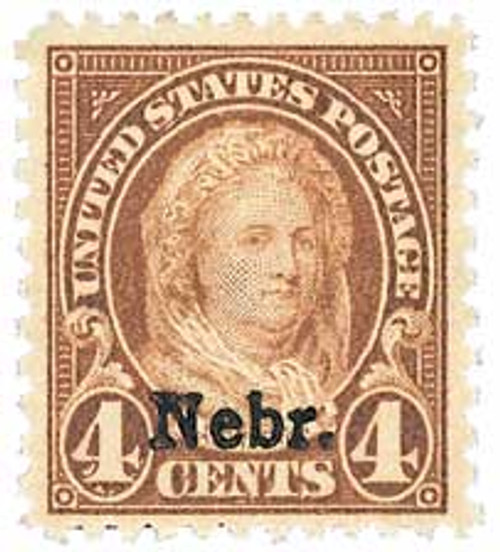

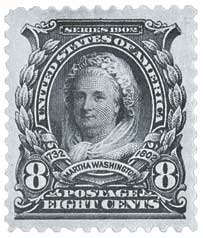

# 673 - 1929 4c Martha Washington, yellow brown, Kansas-Nebraska overprints

1929 Kansas-Nebraska Overprints

4¢ Nebraska

First City: Beatrice, NE; Hartington, NE

Quantity Issued: 1,600,000

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Perforation: 11 x 10.5

Color: Yellow brown

Birth Of Martha Washington

Americas first First Lady was born Martha Dandridge on June 2, 1731 (by the Old Style calendar), on her parents Chestnut Grove Plantation near Williamsburg, Virginia.

The oldest daughter of planter John Dandridge and his wife Frances Jones, Martha had a privileged childhood. She enjoyed riding horses, gardening, sewing, playing the spinet piano, and dancing. She also received an education in basic mathematics, reading, and writing an uncommon practice for girls of the time. She may have been educated by family servant Thomas Leonard in plantation management, crop sales, alternative medicine, and breeding and raising livestock.

When Martha was 18, she met and married Daniel Parke Custis, a wealthy plantation owner who was about 20 years older than her. The couple lived at Custis's White House Plantation on the Pamunkey River. Custis showered Martha with the finest clothes and lavish gifts imported from England. Martha gave birth to four children, two (Daniel and Frances) who died in childhood, and two (John and Martha) who died before the age of 30. In 1757, Custis died, leaving Martha the wealthiest widow in the region, and in full charge of the 17,000-acre plantation.

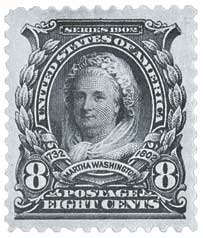

1929 Kansas-Nebraska Overprints

4¢ Nebraska

First City: Beatrice, NE; Hartington, NE

Quantity Issued: 1,600,000

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Perforation: 11 x 10.5

Color: Yellow brown

Birth Of Martha Washington

Americas first First Lady was born Martha Dandridge on June 2, 1731 (by the Old Style calendar), on her parents Chestnut Grove Plantation near Williamsburg, Virginia.

The oldest daughter of planter John Dandridge and his wife Frances Jones, Martha had a privileged childhood. She enjoyed riding horses, gardening, sewing, playing the spinet piano, and dancing. She also received an education in basic mathematics, reading, and writing an uncommon practice for girls of the time. She may have been educated by family servant Thomas Leonard in plantation management, crop sales, alternative medicine, and breeding and raising livestock.

When Martha was 18, she met and married Daniel Parke Custis, a wealthy plantation owner who was about 20 years older than her. The couple lived at Custis's White House Plantation on the Pamunkey River. Custis showered Martha with the finest clothes and lavish gifts imported from England. Martha gave birth to four children, two (Daniel and Frances) who died in childhood, and two (John and Martha) who died before the age of 30. In 1757, Custis died, leaving Martha the wealthiest widow in the region, and in full charge of the 17,000-acre plantation.