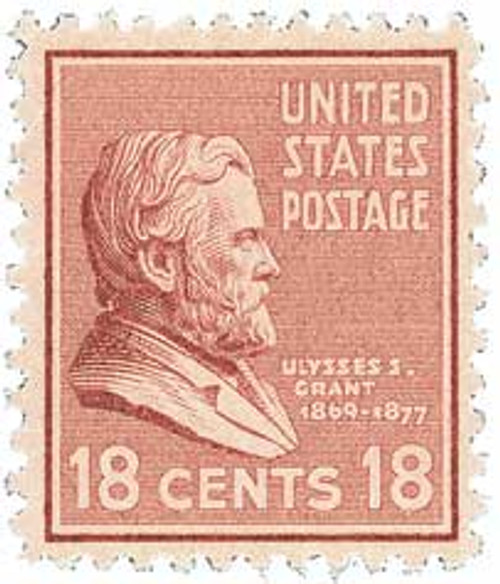

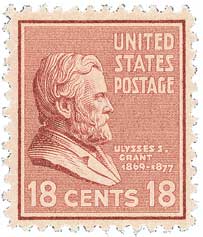

# 823 - 1938 18c Grant, red brown

1938 18¢ Ulysses S. Grant

Presidential Series

Issue Date: November 3, 1938

First City: Washington, DC

Quantity Issued: 170,350,800

Printing Method: Rotary press

Perforations: 11 x 10 ½

Color: Brown carmine

Start Of The Battle Of Cold Harbor

By May 1864, the Union Army of the Potomac was within a few miles of the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia. Commander Ulysses S. Grant not only wanted to capture the city, but to destroy the opposing Army of Northern Virginia as well.

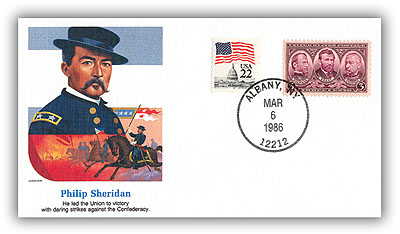

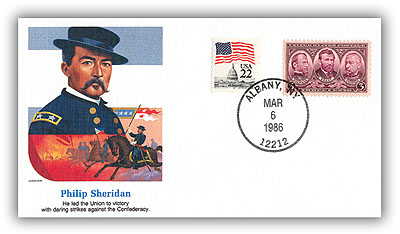

Philip Sheridan’s cavalry was the first to arrive at the crossroads of Old Cold Harbor on May 31. His men secured the area until reinforcements arrived. Meanwhile, Confederate forces under General Robert E. Lee were amassing nearby. By the time all divisions had gathered, the Union Army consisted of 108,000 men and the Confederates were 62,000 strong. Both commanders planned to attack at first light the next day.

The Southern Army was the first to strike. A brigade under an inexperienced colonel led the assault, but it was quickly repelled by the Union cavalry entrenched near the crossroads. The attackers, who lacked experience as well, fled back to the safety of their camp.

On the Union side, action was delayed by the late arrival of a number of units, and the attack finally began at 6:30 p.m. The Federal troops faced withering gunfire all along the Confederate line. Only one brigade found a gap and broke through. Southern soldiers swung around and surrounded the enemy, forcing them to retreat, but the Northern brigade was able to take hundreds of prisoners with them. The fighting ended when darkness fell.

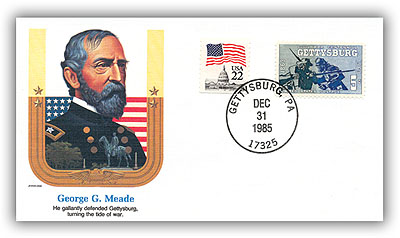

Grant’s second in command, Major General George Meade, believed an attack against the South would be successful if the Union employed greater numbers against Lee’s right flank, which had been involved in the previous day’s fighting and did not have time to fortify its position. It took most of the day for enough divisions to arrive, and they needed to rest after their march. Grant delayed the plan until the following morning.

Lee’s army took advantage of the relative quiet to build up their fortifications. They also set up obstacles along roadways and sighted in their artillery. Grant’s delay would prove very costly.

As morning dawned on June 3, the Union met with stiff Confederate opposition all along the seven-mile front. Only one Northern corps broke through that day, and they drove the defenders out of their trenches in hand-to-hand combat. Several hundred prisoners and four guns were captured. Eventually the Union forces were driven off, and the division commanders refused to subject their men to more futile fighting, in spite of Grant’s orders.

Over the course of the next nine days, there were no more attacks. Both sides sought refuge in their trenches, often just yards away from one another. Sharpshooters and occasional artillery fire raised the casualty rate, but gave neither side an advantage.

Wounded Federal soldiers remained between the lines. Grant refused to ask for a formal truce to recover the men, reasoning it would be admitting the Union lost the battle.

On the night of June 12, Grant pulled his army away from Cold Harbor. After marching to the James River, the Army of the Potomac crossed by ferry and pontoon bridge and headed south.

The loss at Cold Harbor increased anti-war sentiments in the North, and Grant became known as the “fumbling butcher.” While the victory boosted the morale of the South’s Army of Northern Virginia, it had the opposite effect on the Army of the Potomac. Grant no longer attempted to reach the Confederate capital of Richmond, instead setting his sights on Petersburg, a vital supply link for the South.

The Battle of Cold Harbor was the last victory for General Lee. The nine-month siege of Petersburg that followed led to the Confederacy’s surrender on April 9, 1865.

1938 18¢ Ulysses S. Grant

Presidential Series

Issue Date: November 3, 1938

First City: Washington, DC

Quantity Issued: 170,350,800

Printing Method: Rotary press

Perforations: 11 x 10 ½

Color: Brown carmine

Start Of The Battle Of Cold Harbor

By May 1864, the Union Army of the Potomac was within a few miles of the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia. Commander Ulysses S. Grant not only wanted to capture the city, but to destroy the opposing Army of Northern Virginia as well.

Philip Sheridan’s cavalry was the first to arrive at the crossroads of Old Cold Harbor on May 31. His men secured the area until reinforcements arrived. Meanwhile, Confederate forces under General Robert E. Lee were amassing nearby. By the time all divisions had gathered, the Union Army consisted of 108,000 men and the Confederates were 62,000 strong. Both commanders planned to attack at first light the next day.

The Southern Army was the first to strike. A brigade under an inexperienced colonel led the assault, but it was quickly repelled by the Union cavalry entrenched near the crossroads. The attackers, who lacked experience as well, fled back to the safety of their camp.

On the Union side, action was delayed by the late arrival of a number of units, and the attack finally began at 6:30 p.m. The Federal troops faced withering gunfire all along the Confederate line. Only one brigade found a gap and broke through. Southern soldiers swung around and surrounded the enemy, forcing them to retreat, but the Northern brigade was able to take hundreds of prisoners with them. The fighting ended when darkness fell.

Grant’s second in command, Major General George Meade, believed an attack against the South would be successful if the Union employed greater numbers against Lee’s right flank, which had been involved in the previous day’s fighting and did not have time to fortify its position. It took most of the day for enough divisions to arrive, and they needed to rest after their march. Grant delayed the plan until the following morning.

Lee’s army took advantage of the relative quiet to build up their fortifications. They also set up obstacles along roadways and sighted in their artillery. Grant’s delay would prove very costly.

As morning dawned on June 3, the Union met with stiff Confederate opposition all along the seven-mile front. Only one Northern corps broke through that day, and they drove the defenders out of their trenches in hand-to-hand combat. Several hundred prisoners and four guns were captured. Eventually the Union forces were driven off, and the division commanders refused to subject their men to more futile fighting, in spite of Grant’s orders.

Over the course of the next nine days, there were no more attacks. Both sides sought refuge in their trenches, often just yards away from one another. Sharpshooters and occasional artillery fire raised the casualty rate, but gave neither side an advantage.

Wounded Federal soldiers remained between the lines. Grant refused to ask for a formal truce to recover the men, reasoning it would be admitting the Union lost the battle.

On the night of June 12, Grant pulled his army away from Cold Harbor. After marching to the James River, the Army of the Potomac crossed by ferry and pontoon bridge and headed south.

The loss at Cold Harbor increased anti-war sentiments in the North, and Grant became known as the “fumbling butcher.” While the victory boosted the morale of the South’s Army of Northern Virginia, it had the opposite effect on the Army of the Potomac. Grant no longer attempted to reach the Confederate capital of Richmond, instead setting his sights on Petersburg, a vital supply link for the South.

The Battle of Cold Harbor was the last victory for General Lee. The nine-month siege of Petersburg that followed led to the Confederacy’s surrender on April 9, 1865.