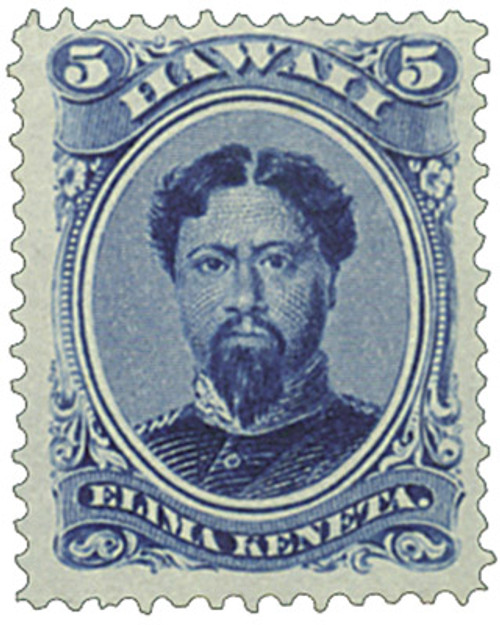

# H10R - 1889 5c Hawaii Reprint Blue

Get Your Official Hawaii Reprint Stamp

This stamp is an official imitation of the 5¢ Hawaii stamp issued in 1853. It was reprinted in 1889 for philatelic purposes and was never intended to be used as postage.

The 1853 stamp had become obsolete, but it was reissued in 1866 for the benefit of collectors and dealers, as well as for exchange with other postal administrations around the world. In 1887, Hawaii’s Postmaster General wanted a new printing of the 5¢ and 13¢ stamps, to be sold to collectors and dealers as the previous reissues had been. Because the plates had been destroyed, he sent the original die of the 5¢ stamp to the American Bank Note Co. in New York, which had printing Hawaii’s stamps since 1878. The die was retouched and a printing plate was made. The original die was modified to create a printing plate for the 13¢ stamp. The new stamps were delivered to Honolulu in September 1889 and sold to collectors. Some were used as postage. To prevent further use, the word REPRINT was overprinted on the remaining supply in 1892.

Kamehameha III

King Kamehameha III’s 30-year reign lasted the longest of any recorded Hawaiian monarch. Kamehameha III, originally named Kauikeaouli, was an effective, generous, and diplomatic ruler. He became king at the tender age of 10, but he was not an official ruler until 1833, when he reached 29.

Kamehameha III made sweeping changes in the governmental policies of the Sandwich Islands. He was heavily influenced by democratic ideals, and was the first Hawaiian monarch to limit the powers of the king. He succeeded in implementing a constitution based on that of the U.S. One of his first acts as king was the declaration of religious freedom. Prior to this edict, Catholic missionaries and their followers had been persecuted and imprisoned.

In 1839, Captain Cyrille Laplace arrived in the Sandwich Islands on a 60-gun French frigate, the Artémise, with several demands and the promise that war would ensue if his ultimatums were not met. His demands were for: amnesty of Catholics previously imprisoned, donation of a site for a church, freedom of Catholic worship, and $20,000 payment to the government of France. Although the king was absent throughout this crisis, the captain’s demands were met, and Laplace returned to France.

The next challenge to Kamehameha’s authority was a demand by Richard Charlton, British consul at Honolulu, that Kamehameha abdicate the throne and turn the Sandwich Islands over to British rule. When British troops took up posts in Honolulu, a provisional cession of the islands to Great Britain was granted by Kamehameha, through no choice of his own. When Charlton’s superiors in the British Navy learned of his reprehensible behavior, they reversed his decision. The Sandwich Islands once again belonged to its people. Upon hearing this news, Kamehameha proclaimed in a speech to the inhabitants of the islands, “The life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness.” It is the state motto to this day.

Perhaps the most radical change in government policy was the privatization of land. The king renounced his right to ownership of all land. After a three-year study by the king, a group of high chiefs and nobles, the “Great Mahele,” or land division, was decided upon. The land was split into thirds, the King, the chiefs, and the people each receiving a share of land. Kamehameha divided his share of land – keeping only half for himself, and the other half was donated to the monarchy. This noble act caused many of the chiefs to follow his example.

Kamehameha III was a superb leader. He was civic-minded, benevolent, and innovative. Beginning to feel pressure from different groups in the Sandwich Islands, Kamehameha III was considering cession of the islands to America at the time of his death in 1854. He was succeeded by Prince Alexander Liholiho, grandson of Kamehameha I, who took the name Kamehameha IV after being proclaimed king.

Get Your Official Hawaii Reprint Stamp

This stamp is an official imitation of the 5¢ Hawaii stamp issued in 1853. It was reprinted in 1889 for philatelic purposes and was never intended to be used as postage.

The 1853 stamp had become obsolete, but it was reissued in 1866 for the benefit of collectors and dealers, as well as for exchange with other postal administrations around the world. In 1887, Hawaii’s Postmaster General wanted a new printing of the 5¢ and 13¢ stamps, to be sold to collectors and dealers as the previous reissues had been. Because the plates had been destroyed, he sent the original die of the 5¢ stamp to the American Bank Note Co. in New York, which had printing Hawaii’s stamps since 1878. The die was retouched and a printing plate was made. The original die was modified to create a printing plate for the 13¢ stamp. The new stamps were delivered to Honolulu in September 1889 and sold to collectors. Some were used as postage. To prevent further use, the word REPRINT was overprinted on the remaining supply in 1892.

Kamehameha III

King Kamehameha III’s 30-year reign lasted the longest of any recorded Hawaiian monarch. Kamehameha III, originally named Kauikeaouli, was an effective, generous, and diplomatic ruler. He became king at the tender age of 10, but he was not an official ruler until 1833, when he reached 29.

Kamehameha III made sweeping changes in the governmental policies of the Sandwich Islands. He was heavily influenced by democratic ideals, and was the first Hawaiian monarch to limit the powers of the king. He succeeded in implementing a constitution based on that of the U.S. One of his first acts as king was the declaration of religious freedom. Prior to this edict, Catholic missionaries and their followers had been persecuted and imprisoned.

In 1839, Captain Cyrille Laplace arrived in the Sandwich Islands on a 60-gun French frigate, the Artémise, with several demands and the promise that war would ensue if his ultimatums were not met. His demands were for: amnesty of Catholics previously imprisoned, donation of a site for a church, freedom of Catholic worship, and $20,000 payment to the government of France. Although the king was absent throughout this crisis, the captain’s demands were met, and Laplace returned to France.

The next challenge to Kamehameha’s authority was a demand by Richard Charlton, British consul at Honolulu, that Kamehameha abdicate the throne and turn the Sandwich Islands over to British rule. When British troops took up posts in Honolulu, a provisional cession of the islands to Great Britain was granted by Kamehameha, through no choice of his own. When Charlton’s superiors in the British Navy learned of his reprehensible behavior, they reversed his decision. The Sandwich Islands once again belonged to its people. Upon hearing this news, Kamehameha proclaimed in a speech to the inhabitants of the islands, “The life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness.” It is the state motto to this day.

Perhaps the most radical change in government policy was the privatization of land. The king renounced his right to ownership of all land. After a three-year study by the king, a group of high chiefs and nobles, the “Great Mahele,” or land division, was decided upon. The land was split into thirds, the King, the chiefs, and the people each receiving a share of land. Kamehameha divided his share of land – keeping only half for himself, and the other half was donated to the monarchy. This noble act caused many of the chiefs to follow his example.

Kamehameha III was a superb leader. He was civic-minded, benevolent, and innovative. Beginning to feel pressure from different groups in the Sandwich Islands, Kamehameha III was considering cession of the islands to America at the time of his death in 1854. He was succeeded by Prince Alexander Liholiho, grandson of Kamehameha I, who took the name Kamehameha IV after being proclaimed king.