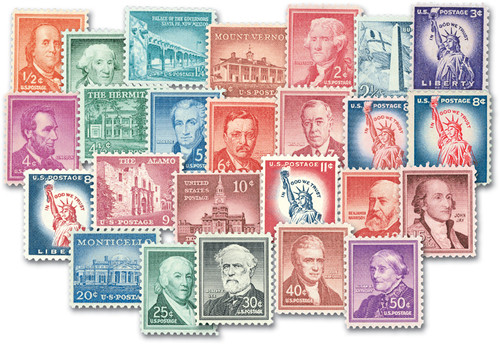

1954 Liberty Series,4¢ Abraham Lincoln

# 1036 - 1954 Liberty Series - 4¢ Abraham Lincoln

MSRP:

Was:

Now:

$0.35 - $35.00

(You save

)

Write a Review

Write a Review

1036 - 1954 Liberty Series - 4¢ Abraham Lincoln

| Image | Condition | Price | Qty | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Classic First Day Cover

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 1.75

|

$ 1.75 |

|

0

|

|

First Day Cover Plate Block

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 2.50

|

$ 2.50 |

|

1

|

|

Mint Plate Block

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 2.00

|

$ 2.00 |

|

2

|

|

Mint Stamp(s)

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 0.40

|

$ 0.40 |

|

3

|

|

Mint Sheet(s)

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 35.00

|

$ 35.00 |

|

4

|

|

Used Single Stamp(s)

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 0.35

|

$ 0.35 |

|

5

|

|

Used Stamps, Glassine of 100

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 2.95

|

$ 2.95 |

|

6

|

|

Used Stamps, Glassine of 1,000

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 14.95

|

$ 14.95 |

|

7

|

|

Fleetwood First Day Cover

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 2.50

|

$ 2.50 |

|

8

|

Mounts - Click Here

| Mount | Price | Qty |

|---|

U.S. #1036

4¢ Abraham Lincoln

Liberty Series

4¢ Abraham Lincoln

Liberty Series

Issue Date: November 19, 1954

City: New York, NY

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Perforations: 11 x 10½

Color: Red violet

City: New York, NY

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Perforations: 11 x 10½

Color: Red violet

Abraham Lincoln Is Awarded Patent

On May 22, 1849, Abraham Lincoln became the only future U.S. president to receive a patent.

The image of Abraham Lincoln on U.S. #1036 is based on a portrait by Douglas Volk.

U.S. #1036

4¢ Abraham Lincoln

Liberty Series

4¢ Abraham Lincoln

Liberty Series

Issue Date: November 19, 1954

City: New York, NY

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Perforations: 11 x 10½

Color: Red violet

City: New York, NY

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Perforations: 11 x 10½

Color: Red violet

Abraham Lincoln Is Awarded Patent

On May 22, 1849, Abraham Lincoln became the only future U.S. president to receive a patent.

The image of Abraham Lincoln on U.S. #1036 is based on a portrait by Douglas Volk.

!