1963 5c Civil War Centennial: Battle of Gettysburg

# 1180 - 1963 5c Civil War Centennial: Battle of Gettysburg

$0.35 - $30.00

U.S. #1180

4¢ Gettysburg

Civil War Centennial Series

4¢ Gettysburg

Civil War Centennial Series

Issue Date: July 1, 1963

City: Gettysburg, PA

Quantity: 79,905,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Giori Press

Perforations: 11

Color: Gray and blue

City: Gettysburg, PA

Quantity: 79,905,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Giori Press

Perforations: 11

Color: Gray and blue

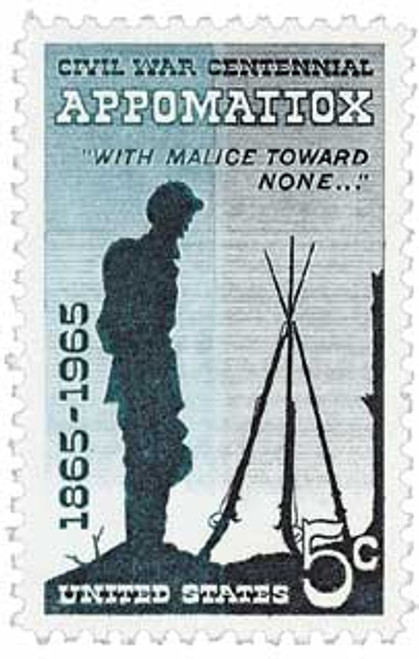

U.S. #1180 honors the Battle of Gettysburg. The stamp image is the result of the first nationwide contest sponsored by the Post Office Department inviting professional artists to design a U.S. postage stamp. Pictured are a Confederate soldier on a gray background and Union soldier on a blue background.

U.S. #1180

4¢ Gettysburg

Civil War Centennial Series

4¢ Gettysburg

Civil War Centennial Series

Issue Date: July 1, 1963

City: Gettysburg, PA

Quantity: 79,905,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Giori Press

Perforations: 11

Color: Gray and blue

City: Gettysburg, PA

Quantity: 79,905,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Giori Press

Perforations: 11

Color: Gray and blue

U.S. #1180 honors the Battle of Gettysburg. The stamp image is the result of the first nationwide contest sponsored by the Post Office Department inviting professional artists to design a U.S. postage stamp. Pictured are a Confederate soldier on a gray background and Union soldier on a blue background.