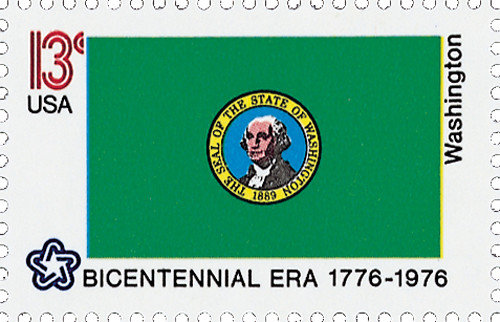

# 1663 - 1976 13c State Flags: California

U.S. 1663

1976 California

State Flags

American Bicentennial Series

• First time a sheet 50 had all different stamp designs

• Part of the American Bicentennial Series

Stamp Category: Commemorative

Series: American Bicentennial Series

Value: 13¢ First-class postage rate

First Day of Issue: February 23, 1976

First Day City(s): Washington, DC

Quantity Issued: 8,720,100 (panes of 50)

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Photogravure

Format: Sheet of 50

Perforations: 11

Why the stamp was issued:

The United States Postal Service celebrated the American Bicentennial with a full pane of the Union’s fifty state flags.

About the stamp design:

Military explorer John C. Frémont led surveying parties into California from 1844 to 1846. The Mexicans saw these expeditions as a threat. In March 1846, the Mexicans ordered Frémont to leave the area. Instead, he stood his ground, raising the US flag over Hawk’s Peak, located about 25 miles from Monterey. Frémont began building a fort, but when Mexican troops came to the area, Frémont withdrew. On May 13, 1846, the US and Mexico went to war.

Meanwhile, in Sonoma, California, settlers were emboldened by Frémont’s actions. On June 14, 1846, a group of about 30 Americans led by William Ide and Ezekiel Merritt captured the Mexican fort at Sonoma. This fort served as Mexico’s headquarters for all of northern California. Though Frémont didn’t participate, he approved of their attack.

The Americans surrounded the home of Mexican general Mariano Vallejo, who actually supported American annexation. Still, they told him he was a prisoner of war and he invited them in to discuss the situation over drinks. After several hours of polite discussion, Ide burst in and arrested Vallejo and his family.

The settlers proclaimed a victory and declared California an independent republic. They then raised a homemade flag bearing a star, grizzly bear, and the words California Republic. The Bear Flag Revolt as it came to be known, continued on with the rebels winning a few small skirmishes against the Mexican forces. Frémont then took command of the settlers on July 1.

Then, six days later, Frémont learned that American forces had taken Monterey without a fight and had raised the American flag over California. Because their goal was to make California part of the US, the Bear Flaggers were content, their republic dissolved, and they replaced the flag with the stars and stripes. After the war, Mexico surrendered California in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. California then became part of the US.

William L. Todd was one of the Bear Flag rebels and the designer of the flag. He was a first cousin to Mary Todd Lincoln, the wife of future president Abraham Lincoln. The flag includes a single red star, in honor of the 1836 coup led by Juan Alvarado. Alvarado waved a red lone star flag when he attempted to declare California’s independence from Mexico. The flag’s central feature is the large grizzly bear, native to the state of California, chosen as a symbol of strength. The Bear Flag was officially adopted as the California state flag in 1911.

About the printing process:

Printed by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing on their seven-color Andreotti gravure press (601) which was their work horse for multicolored stamps.

About the American Bicentennial Series:

In the 1970s, America celebrated its 200th anniversary with hundreds of national events commemorating the heroes and historic events that led to our nation’s independence from Great Britain. The U.S. Postal Service issued 113 commemorative stamps over a six-year period in honor of the U.S. bicentennial, beginning with the American Revolution Bicentennial Commission Emblem stamp (U.S. #1432). As a group, the Bicentennial Series chronicles one of our nation’s most important chapters, and remembers the events and patriots who made the U.S. a world model for liberty.

Several of the stamps honored colonial life – craftsmen and communication. Other stamps honored important battles including Lexington and Concord, Bunker Hill, and Saratoga. Significant events such as the Boston Tea Party, the meeting of the First Continental Congress, and the Declaration of Independence were featured as well. The stamps also honored many significant people such as George Washington, Sybil Ludington, Salem Poor, and the Marquis de Lafayette.

Many of the stamps feature classic artwork. For instance, the set of four souvenir sheets picture important events recreated by noted artists such as John Trumbull. The Bicentennial Series also includes an important US postal first – the first 50-stamp se-tenant – featuring all 50 state flags. The format proved to be popular with collectors, and has been repeated many times since.

The American Bicentennial Series is packed with important US history – it tells the story of our nation’s fight for independence through stamps.

History the stamp represents:

On September 9, 1850, California became America’s 31st state.

Long before Europeans first explored California, it was inhabited by as many as 300,000 Indians. The Hupa and Pomo tribes lived in the north, the Maidu in the central region, and the Yuma in the south. Because of the region’s high mountains and vast deserts, these groups were isolated from one another, as well as from people farther east.

In 1542, Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, a Portuguese explorer employed by Spain, became the first European to sail along the coast of California. In 1579, Sir Francis Drake claimed the land for England. Afraid they were losing the region to the English, Spain sent more exploring parties to California. One of these explorers, Sebastián Vizcaíno, urged Spain to colonize the area before England had the chance.

In 1769, Captain Gaspar de Portolá, governor of Baja California, founded a military fort at San Diego. That same year, also in San Diego, Father Junipero Serra established the first California Mission. Over the next 13 years, Father Serra founded eight more. By 1823, there were 21 missions in California, each within a day’s walk of the previous one.

Despite the large missionary presence, Spain did not have firm control over the region. In 1812, Russian fur traders from Alaska established Fort Ross on the northern California coast. Twelve years later, in response to the Monroe Doctrine – which was in part influenced by Russia’s expansion into the area – Russia agreed to limit its trapping to Alaska. However, the Russians did not leave Fort Ross until the early 1840s.

The missions were a powerful economic force. Many Indians who lived in these missions were forced to do hard labor for long hours. Also, as a number of Indians were exposed to new diseases, many became ill and died. Quite a number of people in California and Mexico wanted the missions shut down. As a result, the government began selling the missions in the 1830s. By 1846, nearly all the mission property had been sold.

In 1821, Mexico won its independence from Spain. A year later, California became a province of Mexico. The province was allowed to establish its own legislature and military force. But when Mexico began sending governors to the province in 1825, Californians began to resent the outside influence. Some citizens engaged Mexican troops in some minor conflicts. This continued resistance weakened Mexico’s control of the area.

In 1796, the Otter became the first American sailing vessel to reach California’s coast from the East. Many other ships soon began making this profitable voyage. In 1826, trapper Jedediah Strong Smith became the first American explorer to reach California by land. Many trappers and explorers soon followed in his footsteps. The first group of American settlers reached California in 1841. A schoolteacher, John Bidwell, and a wagon master and land speculator, John Bartleson, led these people. Wagon trains of settlers soon followed. So many American settlers poured into California that the United States offered to buy the land, but Mexico refused to sell.

Military explorer John C. Frémont led surveying parties into California from 1844 to 1846. The Mexicans saw these expeditions as a threat. In March 1846, the Mexicans ordered Frémont to leave the area. Instead, he stood his ground, raising the US flag over Hawk’s Peak, located about 25 miles from Monterey. Frémont began building a fort, but when Mexican troops came to the area, Frémont withdrew. On May 13, 1846, the US and Mexico went to war.

In June 1846, California settlers, led by frontiersman Ezekiel Merritt, captured the Mexican fort at Sonoma. This fort served as Mexico’s headquarters for all of northern California. After capturing the fort, the settlers raised a homemade flag picturing a star, grizzly bear, and the words California Republic. This event became known as the Bear Flag Revolt.

The Bear Flag Revolt was not a significant military action. Regular US armed forces completed the real military conquest of California. Frémont, Commodore Robert F. Stockton, and General Stephen W. Kearny led US troops. After the war, Mexico surrendered California in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. California then became part of the US.

Gold was discovered in California in 1848 – just before the US and Mexico signed the peace treaty. The gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill in the Sacramento Valley, on land granted to pioneer-trader John A. Sutter. Sutter hired carpenter James W. Marshall to construct a sawmill. It was Marshall who discovered the area’s first gold nuggets.

News of this discovery spread like wildfire, and thousands of miners rushed to establish claims. These miners became known as “Forty-Niners,” and they came from all over the world. Between 1848 and 1849, California’s population grew from about 15,000 to well over 100,000. The wealth generated by gold transformed small communities like San Francisco and Sacramento into flourishing towns.

U.S. 1663

1976 California

State Flags

American Bicentennial Series

• First time a sheet 50 had all different stamp designs

• Part of the American Bicentennial Series

Stamp Category: Commemorative

Series: American Bicentennial Series

Value: 13¢ First-class postage rate

First Day of Issue: February 23, 1976

First Day City(s): Washington, DC

Quantity Issued: 8,720,100 (panes of 50)

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Photogravure

Format: Sheet of 50

Perforations: 11

Why the stamp was issued:

The United States Postal Service celebrated the American Bicentennial with a full pane of the Union’s fifty state flags.

About the stamp design:

Military explorer John C. Frémont led surveying parties into California from 1844 to 1846. The Mexicans saw these expeditions as a threat. In March 1846, the Mexicans ordered Frémont to leave the area. Instead, he stood his ground, raising the US flag over Hawk’s Peak, located about 25 miles from Monterey. Frémont began building a fort, but when Mexican troops came to the area, Frémont withdrew. On May 13, 1846, the US and Mexico went to war.

Meanwhile, in Sonoma, California, settlers were emboldened by Frémont’s actions. On June 14, 1846, a group of about 30 Americans led by William Ide and Ezekiel Merritt captured the Mexican fort at Sonoma. This fort served as Mexico’s headquarters for all of northern California. Though Frémont didn’t participate, he approved of their attack.

The Americans surrounded the home of Mexican general Mariano Vallejo, who actually supported American annexation. Still, they told him he was a prisoner of war and he invited them in to discuss the situation over drinks. After several hours of polite discussion, Ide burst in and arrested Vallejo and his family.

The settlers proclaimed a victory and declared California an independent republic. They then raised a homemade flag bearing a star, grizzly bear, and the words California Republic. The Bear Flag Revolt as it came to be known, continued on with the rebels winning a few small skirmishes against the Mexican forces. Frémont then took command of the settlers on July 1.

Then, six days later, Frémont learned that American forces had taken Monterey without a fight and had raised the American flag over California. Because their goal was to make California part of the US, the Bear Flaggers were content, their republic dissolved, and they replaced the flag with the stars and stripes. After the war, Mexico surrendered California in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. California then became part of the US.

William L. Todd was one of the Bear Flag rebels and the designer of the flag. He was a first cousin to Mary Todd Lincoln, the wife of future president Abraham Lincoln. The flag includes a single red star, in honor of the 1836 coup led by Juan Alvarado. Alvarado waved a red lone star flag when he attempted to declare California’s independence from Mexico. The flag’s central feature is the large grizzly bear, native to the state of California, chosen as a symbol of strength. The Bear Flag was officially adopted as the California state flag in 1911.

About the printing process:

Printed by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing on their seven-color Andreotti gravure press (601) which was their work horse for multicolored stamps.

About the American Bicentennial Series:

In the 1970s, America celebrated its 200th anniversary with hundreds of national events commemorating the heroes and historic events that led to our nation’s independence from Great Britain. The U.S. Postal Service issued 113 commemorative stamps over a six-year period in honor of the U.S. bicentennial, beginning with the American Revolution Bicentennial Commission Emblem stamp (U.S. #1432). As a group, the Bicentennial Series chronicles one of our nation’s most important chapters, and remembers the events and patriots who made the U.S. a world model for liberty.

Several of the stamps honored colonial life – craftsmen and communication. Other stamps honored important battles including Lexington and Concord, Bunker Hill, and Saratoga. Significant events such as the Boston Tea Party, the meeting of the First Continental Congress, and the Declaration of Independence were featured as well. The stamps also honored many significant people such as George Washington, Sybil Ludington, Salem Poor, and the Marquis de Lafayette.

Many of the stamps feature classic artwork. For instance, the set of four souvenir sheets picture important events recreated by noted artists such as John Trumbull. The Bicentennial Series also includes an important US postal first – the first 50-stamp se-tenant – featuring all 50 state flags. The format proved to be popular with collectors, and has been repeated many times since.

The American Bicentennial Series is packed with important US history – it tells the story of our nation’s fight for independence through stamps.

History the stamp represents:

On September 9, 1850, California became America’s 31st state.

Long before Europeans first explored California, it was inhabited by as many as 300,000 Indians. The Hupa and Pomo tribes lived in the north, the Maidu in the central region, and the Yuma in the south. Because of the region’s high mountains and vast deserts, these groups were isolated from one another, as well as from people farther east.

In 1542, Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, a Portuguese explorer employed by Spain, became the first European to sail along the coast of California. In 1579, Sir Francis Drake claimed the land for England. Afraid they were losing the region to the English, Spain sent more exploring parties to California. One of these explorers, Sebastián Vizcaíno, urged Spain to colonize the area before England had the chance.

In 1769, Captain Gaspar de Portolá, governor of Baja California, founded a military fort at San Diego. That same year, also in San Diego, Father Junipero Serra established the first California Mission. Over the next 13 years, Father Serra founded eight more. By 1823, there were 21 missions in California, each within a day’s walk of the previous one.

Despite the large missionary presence, Spain did not have firm control over the region. In 1812, Russian fur traders from Alaska established Fort Ross on the northern California coast. Twelve years later, in response to the Monroe Doctrine – which was in part influenced by Russia’s expansion into the area – Russia agreed to limit its trapping to Alaska. However, the Russians did not leave Fort Ross until the early 1840s.

The missions were a powerful economic force. Many Indians who lived in these missions were forced to do hard labor for long hours. Also, as a number of Indians were exposed to new diseases, many became ill and died. Quite a number of people in California and Mexico wanted the missions shut down. As a result, the government began selling the missions in the 1830s. By 1846, nearly all the mission property had been sold.

In 1821, Mexico won its independence from Spain. A year later, California became a province of Mexico. The province was allowed to establish its own legislature and military force. But when Mexico began sending governors to the province in 1825, Californians began to resent the outside influence. Some citizens engaged Mexican troops in some minor conflicts. This continued resistance weakened Mexico’s control of the area.

In 1796, the Otter became the first American sailing vessel to reach California’s coast from the East. Many other ships soon began making this profitable voyage. In 1826, trapper Jedediah Strong Smith became the first American explorer to reach California by land. Many trappers and explorers soon followed in his footsteps. The first group of American settlers reached California in 1841. A schoolteacher, John Bidwell, and a wagon master and land speculator, John Bartleson, led these people. Wagon trains of settlers soon followed. So many American settlers poured into California that the United States offered to buy the land, but Mexico refused to sell.

Military explorer John C. Frémont led surveying parties into California from 1844 to 1846. The Mexicans saw these expeditions as a threat. In March 1846, the Mexicans ordered Frémont to leave the area. Instead, he stood his ground, raising the US flag over Hawk’s Peak, located about 25 miles from Monterey. Frémont began building a fort, but when Mexican troops came to the area, Frémont withdrew. On May 13, 1846, the US and Mexico went to war.

In June 1846, California settlers, led by frontiersman Ezekiel Merritt, captured the Mexican fort at Sonoma. This fort served as Mexico’s headquarters for all of northern California. After capturing the fort, the settlers raised a homemade flag picturing a star, grizzly bear, and the words California Republic. This event became known as the Bear Flag Revolt.

The Bear Flag Revolt was not a significant military action. Regular US armed forces completed the real military conquest of California. Frémont, Commodore Robert F. Stockton, and General Stephen W. Kearny led US troops. After the war, Mexico surrendered California in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. California then became part of the US.

Gold was discovered in California in 1848 – just before the US and Mexico signed the peace treaty. The gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill in the Sacramento Valley, on land granted to pioneer-trader John A. Sutter. Sutter hired carpenter James W. Marshall to construct a sawmill. It was Marshall who discovered the area’s first gold nuggets.

News of this discovery spread like wildfire, and thousands of miners rushed to establish claims. These miners became known as “Forty-Niners,” and they came from all over the world. Between 1848 and 1849, California’s population grew from about 15,000 to well over 100,000. The wealth generated by gold transformed small communities like San Francisco and Sacramento into flourishing towns.