1847 10c Washington, black, imperforate

# 2 - 1847 10c Washington, black, imperforate

$1,495.00 - $12,000.00

U.S. #2

1847 George Washington

- America’s Postage Stamp

- Vignette features the portrait George Washington, first U.S. president and “Father of His Country”

- In demand around the world and increasingly scarce today in any condition

Stamp Category: Definitive

Set: 1847 Issue

Value: 10c – the half ounce letter rate over 300 miles, also letters of one ounce or more.

First Day of Issue: July 1, 1847

First Day City: New York City

Quantity Issued: 863,000

Printed by: Rawden, Wright, Hatch & Edson

Printing Method: Flat plate printing

Format: Sheet of 200 subjects in 2 panes of 100 each

Perforations: Imperforate

Color: 10c – black on thin, bluish wove paper.

Note: Printers Rawden, Wright, Hatch, & Edson originally suggested printing the stamp in two colors.

Why the stamp was issued:

To show pre-payment of the uniform domestic rate for letters of one ounce or more; also, for those weighing up to ½ ounce and being sent over 300 miles.

There are a number of reasons why modernization of America’s postal service was urgently needed. A few of these include the steady flow of immigrants from Europe, the on-going settlement of the West, the Mexican-American War, industrial growth, and conflicts between the states on the issue of slavery. All called for more a rapid and dependable flow of communication.

About the stamp design:

Like the printing dies for U.S. #1, those for U.S. #2 were already in the stocks of the printers, who had previously used them to produce private banknotes.

The engraving for the Washington stamp was done by Asher B. Durand, a well-known American landscape painter. It was based on an unfinished portrait of Washington by Gilbert Stuart.

According to the National Gallery of Art, Gilbert Stuart painted over 100 portraits of George Washington.

Engraver Durand was one of the founders of the Hudson River school and also founded the National Academy of Design.

Special design details: The initials of the printers – RWH&E – appear at the bottom of the stamp, centered inside the frame line.

About the printing process: U.S. #2 was printed by hand, which consisted of line engraving the design onto the steel plate of a flat bed press. The plate was inked and heated. A sheet of damp paper was laid on the plate. A heavy wooden or metal piece on the press, called a platen, was rolled over the plate, transferring the ink to the paper. Each sheet was put aside to dry. All the work was done manually, making for a slow process and only a few thousand stamps printed each day. The early flat bed (or flat plate) press was called a “Spider” press.

Impressions of U.S. #2 are much cleaner than those of U.S #1, as its black ink didn’t contain impurities which could wear the printing plates down.

First Day City: New York City. The stamp was sold in Boston on July 2nd and Philadelphia on July 7th. First documented use of #2 is July 2nd.

About the 1847 Imperforates – U.S. #1 and #2: It may seem surprising George Washington doesn’t appear on our first postage stamp. However, Franklin was highly esteemed for his service in establishing America’s postal system. After serving as postmaster of Philadelphia, he was co-postmaster general for the colonies under British rule. Finally, Franklin was appointed America’s first postmaster general by the 2nd Continental Congress. In addition to his accomplishments in the postal area, he was the central unifying figure for the colonists during the Revolution. That made Franklin a logical choice. This brilliant scientist, diplomat, statesman, printer, inventor, and patriot earned his place in history, as well as on America’s first postage stamp.

Andrew Jackson was the original choice for the subject of US#1.

President George Washington’s portrait has appeared on over 300 U.S. stamps, more than any other president, and more than all other presidents combined.

Margins: The first U.S. postage stamps were issued in large sheets without perforations. Postal clerks simply cut the stamps from the sheet by hand. This accounts for the variation in margins seen on both stamps. Well-centered stamps with large margins are sold at a higher price due to their scarcity.

Prior to the issue of U.S. #1 and #2, a few postage stamps were issued privately by various postmasters. These were called “Postmaster Provisionals”. Once the first two federal postage stamps were issued, Postmaster Provisionals were no longer valid.

If a letter was sent without stamps, marked with the amount to be paid upon receipt or “postage due”, it’s called a stampless cover.

Before the introduction of envelopes, postal customers would either fold a piece of paper around their letters in the shape of an envelope, or fold the letter itself and apply an adhesive or wax seal. Envelopes are referred to as covers. Both U.S. #1and #2 “on cover” are very scarce and worth a lot of money.

History the stamps represent: America followed Great Britain by just a few years when it issued our first general issue pre-paid adhesive postage stamps. These stamps changed our postal service forever – the newest step in making it easier and more efficient to send, receive and deliver the mail. This in turn vastly improved communications across our rapidly expanding country. It was expensive to print the stamps, but cheaper and more efficient to handle the mail.

A stamp to show the pre-payment of postage did away with the need for postmasters to count the number of pages in a letter, and mark the fee on the envelope according to its weight and how far it would travel. Now customers could buy stamps in advance without waiting in line, and drop their letters off in the post office box any time. And the recipient was no longer required to pay the fee at his post office when he picked the letter up. (It wasn’t until years later, in July 1863, that free city delivery to individual addresses became available.)

Pre-paid postage stamps also enabled postal authorities to track sales and have more control over money taken in. Prepayment with a general issue stamp did not become mandatory until January 1st, 1856. Before this time, it was still legal for the addressee to pay the postage or for the sender and recipient to share the cost.

George Washington’s role in U.S. History:

America’s first president was born on February 22, 1732, in Westmoreland County, Virginia. His father died when he was young, halting his plans to study abroad. George’s older half-brother and mentor, Lawrence, took him under his wing and taught him how to farm and survey land. In 1749, George joined a party that explored and surveyed the land west of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

After Lawrence died in 1752, Washington assumed his role as district adjunct in the Virginia militia and achieved the rank of major by the age of 20. He trained in the colonial militia for two years before the French and Indian War escalated. Sent to the Ohio River Valley to represent British interests, Washington was involved in the opening shots of the war. Washington resigned in protest of British indifference to colonists’ contributions.

As one of the state’s wealthiest landowners and a hero of the French and Indian Wars, Washington was appointed to Virginia’s House of Burgesses in 1758. The House stood fast against the Stamp Act of 1765 and other oppressive tax measures proposed by British Parliament. Along with Patrick Henry and Thomas Jefferson, Washington called for a boycott of British goods entering the colonies. The men would later be Virginia’s representatives to the First Continental Congress.

The First Continental Congress closed in the fall of 1774 with plans to hold a second in the spring. Before the Second Continental Congress convened, colonists skirmished with the British in Lexington and Concord. Washington arrived at the Second Continental Congress in full military uniform to signal his intentions, and was selected to be the commander-in-chief of the Continental Army. Washington took command of the estimated 14,500-member Continental Army in Massachusetts in July of 1775 and broke the British siege of Boston.

Short on troops, and aware that he could not win by using traditional military methods, Washington relied on the methods he’d learned fighting Native Americans during the French and Indian War. His strategy harassed the much larger, better-equipped British army through a series of surprise attacks, intentional retreats, and other guerrilla tactics. Washington scored major victories at Trenton and Princeton, before his winter at Valley Forge. He later led his men to an important victory at Yorktown.

Washington resigned his commission as commander-in-chief on December 23, 1783, and looked forward to a quiet retirement with his family at his plantation. However, in 1787, he was called upon to serve as president of the Constitutional Convention. As debate raged between the 55 delegates, Washington’s leadership kept the men on course, and his support convinced many state legislatures to ratify the Constitution.

Among the issues addressed by the Constitutional Convention was the office of a President to head the stronger central government. The delegates defined the office with Washington in mind. The Electoral College elected George Washington as our nation’s first President in 1789. The vote was unanimous, as it would be again in 1792, a feat that has never been duplicated in American history. His salary was $25,000, an enormous sum for that time, and one that Washington tried to decline. Washington was eventually persuaded by the argument that unpaid service would set the dangerous precedent of only allowing wealthy individuals to serve in the nation’s highest office. On April 30, 1789, George Washington was sworn in as the first President of the United States.

In 1793, a war was raging between England, Spain, Prussia, and the newly independent French Republic. Washington signed a neutrality proclamation on April 22, 1793. Although the United States remained neutral in the European conflict, relations with England gradually worsened. To try to repair the wounded relations, Washington sent Chief Justice John Jay to England to work out a treaty. The Jay Treaty stated that British troops would surrender their forts in America and made provisions for future trade between the two countries.

Several treaties followed in the coming months. First, an agreement was reached with Spain to open the Mississippi River for U.S. trade. The Barbary Pirates agreed to release American prisoners and stop waylaying U.S. vessels for a ransom of $642,500 and an annual payment of $21,600. In addition, a peace treaty was signed with the frontier Indians.

In 1797, following his second term, Washington retired to his home at Mount Vernon. He had served his country for 45 of his 67 years. His farewell address is considered one of the most influential statements of American government values. In it, Washington stressed the importance of national unity, the value of the Constitution and the rule of law. He warned against foreign influence in domestic affairs and partisan politics. Washington also expressed hope that the United States would entertain peaceful and prosperous relations with other nations, but warned against American involvement in European wars and long-term alliances with foreign countries. Washington’s farewell address was heeded throughout the 19th century and well into the 20th. In fact, the United States declined to sign a treaty of alliance with a foreign nation until the 1949 formation of NATO.

Washington died at his Mount Vernon home on December 14, 1799. His final words were “Tis well.” He was posthumously appointed to the highest rank of General of the Armies of the United States. The Joint Congressional Resolution, which was approved by President Gerald Ford during the 1976 Bicentennial celebrations, assures that no officer of the American military will ever outrank George Washington.

U.S. #2

1847 George Washington

- America’s Postage Stamp

- Vignette features the portrait George Washington, first U.S. president and “Father of His Country”

- In demand around the world and increasingly scarce today in any condition

Stamp Category: Definitive

Set: 1847 Issue

Value: 10c – the half ounce letter rate over 300 miles, also letters of one ounce or more.

First Day of Issue: July 1, 1847

First Day City: New York City

Quantity Issued: 863,000

Printed by: Rawden, Wright, Hatch & Edson

Printing Method: Flat plate printing

Format: Sheet of 200 subjects in 2 panes of 100 each

Perforations: Imperforate

Color: 10c – black on thin, bluish wove paper.

Note: Printers Rawden, Wright, Hatch, & Edson originally suggested printing the stamp in two colors.

Why the stamp was issued:

To show pre-payment of the uniform domestic rate for letters of one ounce or more; also, for those weighing up to ½ ounce and being sent over 300 miles.

There are a number of reasons why modernization of America’s postal service was urgently needed. A few of these include the steady flow of immigrants from Europe, the on-going settlement of the West, the Mexican-American War, industrial growth, and conflicts between the states on the issue of slavery. All called for more a rapid and dependable flow of communication.

About the stamp design:

Like the printing dies for U.S. #1, those for U.S. #2 were already in the stocks of the printers, who had previously used them to produce private banknotes.

The engraving for the Washington stamp was done by Asher B. Durand, a well-known American landscape painter. It was based on an unfinished portrait of Washington by Gilbert Stuart.

According to the National Gallery of Art, Gilbert Stuart painted over 100 portraits of George Washington.

Engraver Durand was one of the founders of the Hudson River school and also founded the National Academy of Design.

Special design details: The initials of the printers – RWH&E – appear at the bottom of the stamp, centered inside the frame line.

About the printing process: U.S. #2 was printed by hand, which consisted of line engraving the design onto the steel plate of a flat bed press. The plate was inked and heated. A sheet of damp paper was laid on the plate. A heavy wooden or metal piece on the press, called a platen, was rolled over the plate, transferring the ink to the paper. Each sheet was put aside to dry. All the work was done manually, making for a slow process and only a few thousand stamps printed each day. The early flat bed (or flat plate) press was called a “Spider” press.

Impressions of U.S. #2 are much cleaner than those of U.S #1, as its black ink didn’t contain impurities which could wear the printing plates down.

First Day City: New York City. The stamp was sold in Boston on July 2nd and Philadelphia on July 7th. First documented use of #2 is July 2nd.

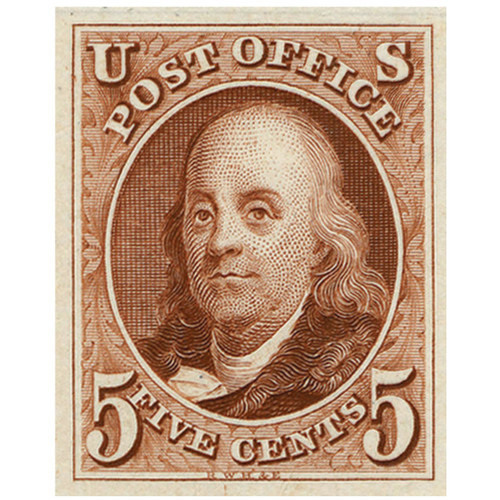

About the 1847 Imperforates – U.S. #1 and #2: It may seem surprising George Washington doesn’t appear on our first postage stamp. However, Franklin was highly esteemed for his service in establishing America’s postal system. After serving as postmaster of Philadelphia, he was co-postmaster general for the colonies under British rule. Finally, Franklin was appointed America’s first postmaster general by the 2nd Continental Congress. In addition to his accomplishments in the postal area, he was the central unifying figure for the colonists during the Revolution. That made Franklin a logical choice. This brilliant scientist, diplomat, statesman, printer, inventor, and patriot earned his place in history, as well as on America’s first postage stamp.

Andrew Jackson was the original choice for the subject of US#1.

President George Washington’s portrait has appeared on over 300 U.S. stamps, more than any other president, and more than all other presidents combined.

Margins: The first U.S. postage stamps were issued in large sheets without perforations. Postal clerks simply cut the stamps from the sheet by hand. This accounts for the variation in margins seen on both stamps. Well-centered stamps with large margins are sold at a higher price due to their scarcity.

Prior to the issue of U.S. #1 and #2, a few postage stamps were issued privately by various postmasters. These were called “Postmaster Provisionals”. Once the first two federal postage stamps were issued, Postmaster Provisionals were no longer valid.

If a letter was sent without stamps, marked with the amount to be paid upon receipt or “postage due”, it’s called a stampless cover.

Before the introduction of envelopes, postal customers would either fold a piece of paper around their letters in the shape of an envelope, or fold the letter itself and apply an adhesive or wax seal. Envelopes are referred to as covers. Both U.S. #1and #2 “on cover” are very scarce and worth a lot of money.

History the stamps represent: America followed Great Britain by just a few years when it issued our first general issue pre-paid adhesive postage stamps. These stamps changed our postal service forever – the newest step in making it easier and more efficient to send, receive and deliver the mail. This in turn vastly improved communications across our rapidly expanding country. It was expensive to print the stamps, but cheaper and more efficient to handle the mail.

A stamp to show the pre-payment of postage did away with the need for postmasters to count the number of pages in a letter, and mark the fee on the envelope according to its weight and how far it would travel. Now customers could buy stamps in advance without waiting in line, and drop their letters off in the post office box any time. And the recipient was no longer required to pay the fee at his post office when he picked the letter up. (It wasn’t until years later, in July 1863, that free city delivery to individual addresses became available.)

Pre-paid postage stamps also enabled postal authorities to track sales and have more control over money taken in. Prepayment with a general issue stamp did not become mandatory until January 1st, 1856. Before this time, it was still legal for the addressee to pay the postage or for the sender and recipient to share the cost.

George Washington’s role in U.S. History:

America’s first president was born on February 22, 1732, in Westmoreland County, Virginia. His father died when he was young, halting his plans to study abroad. George’s older half-brother and mentor, Lawrence, took him under his wing and taught him how to farm and survey land. In 1749, George joined a party that explored and surveyed the land west of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

After Lawrence died in 1752, Washington assumed his role as district adjunct in the Virginia militia and achieved the rank of major by the age of 20. He trained in the colonial militia for two years before the French and Indian War escalated. Sent to the Ohio River Valley to represent British interests, Washington was involved in the opening shots of the war. Washington resigned in protest of British indifference to colonists’ contributions.

As one of the state’s wealthiest landowners and a hero of the French and Indian Wars, Washington was appointed to Virginia’s House of Burgesses in 1758. The House stood fast against the Stamp Act of 1765 and other oppressive tax measures proposed by British Parliament. Along with Patrick Henry and Thomas Jefferson, Washington called for a boycott of British goods entering the colonies. The men would later be Virginia’s representatives to the First Continental Congress.

The First Continental Congress closed in the fall of 1774 with plans to hold a second in the spring. Before the Second Continental Congress convened, colonists skirmished with the British in Lexington and Concord. Washington arrived at the Second Continental Congress in full military uniform to signal his intentions, and was selected to be the commander-in-chief of the Continental Army. Washington took command of the estimated 14,500-member Continental Army in Massachusetts in July of 1775 and broke the British siege of Boston.

Short on troops, and aware that he could not win by using traditional military methods, Washington relied on the methods he’d learned fighting Native Americans during the French and Indian War. His strategy harassed the much larger, better-equipped British army through a series of surprise attacks, intentional retreats, and other guerrilla tactics. Washington scored major victories at Trenton and Princeton, before his winter at Valley Forge. He later led his men to an important victory at Yorktown.

Washington resigned his commission as commander-in-chief on December 23, 1783, and looked forward to a quiet retirement with his family at his plantation. However, in 1787, he was called upon to serve as president of the Constitutional Convention. As debate raged between the 55 delegates, Washington’s leadership kept the men on course, and his support convinced many state legislatures to ratify the Constitution.

Among the issues addressed by the Constitutional Convention was the office of a President to head the stronger central government. The delegates defined the office with Washington in mind. The Electoral College elected George Washington as our nation’s first President in 1789. The vote was unanimous, as it would be again in 1792, a feat that has never been duplicated in American history. His salary was $25,000, an enormous sum for that time, and one that Washington tried to decline. Washington was eventually persuaded by the argument that unpaid service would set the dangerous precedent of only allowing wealthy individuals to serve in the nation’s highest office. On April 30, 1789, George Washington was sworn in as the first President of the United States.

In 1793, a war was raging between England, Spain, Prussia, and the newly independent French Republic. Washington signed a neutrality proclamation on April 22, 1793. Although the United States remained neutral in the European conflict, relations with England gradually worsened. To try to repair the wounded relations, Washington sent Chief Justice John Jay to England to work out a treaty. The Jay Treaty stated that British troops would surrender their forts in America and made provisions for future trade between the two countries.

Several treaties followed in the coming months. First, an agreement was reached with Spain to open the Mississippi River for U.S. trade. The Barbary Pirates agreed to release American prisoners and stop waylaying U.S. vessels for a ransom of $642,500 and an annual payment of $21,600. In addition, a peace treaty was signed with the frontier Indians.

In 1797, following his second term, Washington retired to his home at Mount Vernon. He had served his country for 45 of his 67 years. His farewell address is considered one of the most influential statements of American government values. In it, Washington stressed the importance of national unity, the value of the Constitution and the rule of law. He warned against foreign influence in domestic affairs and partisan politics. Washington also expressed hope that the United States would entertain peaceful and prosperous relations with other nations, but warned against American involvement in European wars and long-term alliances with foreign countries. Washington’s farewell address was heeded throughout the 19th century and well into the 20th. In fact, the United States declined to sign a treaty of alliance with a foreign nation until the 1949 formation of NATO.

Washington died at his Mount Vernon home on December 14, 1799. His final words were “Tis well.” He was posthumously appointed to the highest rank of General of the Armies of the United States. The Joint Congressional Resolution, which was approved by President Gerald Ford during the 1976 Bicentennial celebrations, assures that no officer of the American military will ever outrank George Washington.