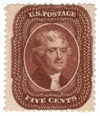

# 28 - 1857-61 5c Jefferson, red brown, type I

U.S. #28

1858 Jefferson, Type I

- Part of the first perforated series of US stamps

- Main usage for paying domestic portion of postage rate on overseas mail going through Britain (British Open Mail rate)

- Often used in threes to pay the postage to France

Stamp Category: Definitive

Series: 1857-61 Issue

Value: 5c

Earliest known Use: August 23, 1857

Printed by: Toppan, Carpenter & Co.

Quantity printed: 270,000 (estimate)

Format: Printed in sheets of 200 stamps, divided into vertical panes of 100 each

Printing Method: Engraving

Perforations: 15½

Color: Red Brown

Why the stamp was issued: The Act of 1855 officially introduced the use of registration of high-value letters to help deter mail theft by robbers and postal workers. The 5c Jefferson stamp was intended for the prepayment of the registration fee, but was not generally required or used for that purpose, as the fee was generally paid in cash.

The 5c denomination did pay the domestic postage portion for letters going to a foreign country if that mail was carried by British packet boats for transport. (Fees for shipping and land transport were paid by the recipient when the letter reached him or her at its destination.)

The 5c Jefferson was also commonly used in a strip of three to pay the postage to France or as a make-up rate in addition to the 10c value.

About the printing: The design is engraved on a die – a small, flat piece of steel. The design is copied to a transfer roll – a blank roll of steel. Several impressions or “reliefs” are made on the roll. The reliefs are transferred to the plate – a large, flat piece of steel from which the stamps are printed.

Types or “varieties” occur when a stamp has differences which vary from the way it was originally engraved. Foreign matter, or damage to or recutting of the plate for any reason, can cause these differences to appear on the stamps printed from it. Major and minor color varieties may also be created when a change is made to the printing ink, as is the case with the 5c Jefferson.

About the design: Thomas Jefferson’s portrait on the #28 is based on a painting by Gilbert Stuart, who also painted many portraits of George Washington.

Special Design Details: US #28 is Type I. The projections on all four sides of the stamp are complete. U.S. #28 is a perforate version of the type I imperforate 5¢ Jefferson stamp of the Series of 1851-57 (#12). The 5c perforated stamps #27, 28A and 29 are also Type I and differ from one another and #28 only in color.

Later recutting of the engraving plates to better accommodate the perforations led to the top and bottom projections being partly cut away, creating the Type II varieties of the 5c denomination (#30 and #30A).

About the 1857-61 Series: In July, 1851 – 1c, 3c, and 12c stamps were issued. The new stamps met reduced postal rates passed by act of Congress on March 3 of the same year. Further changes in postage rates appeared in the Act of March 3, 1855, leading to 10c (1855) and 5c (1856) denominations being added to the series. Perforated stamps of the same designs as the 1851-57 Imperforate Series (plus new denominations of 24c, 30c, and 90c) were issued as part of the Series of 1857-61, the first perforated U.S. stamps.

The new series’ designs were reproduced from the imperforate plates of 1851. Because the same plates were used, the perforated stamp types don’t differ much from the corresponding imperforate stamps. The entire series (U.S. #18-39) is noted for having narrow margins. This is because the perforations took up room normally given to the designs.

History the stamp represents: #28 was part of the first series of perforated U.S. postage stamps. When the world’s first postage stamps were issued, no provision was made for separating the stamps from one another. Post office clerks and stamp users merely cut these “imperforates” apart with scissors or tore them along the edge of a metal rule. A device was needed which would separate the stamps more easily and accurately.

In 1847, Irishman Henry Archer patented a machine that punched holes horizontally and vertically between rows of stamps. Now stamps could be separated without cutting. Perforations also enabled stamps to adhere better to envelopes. Archer sold his invention to the British Treasury in 1853. That same year, Great Britain produced its first perforated stamps. It wasn’t long before the US decided to make use of the new method of producing stamps with perforations, resulting in the Series of 1857-61.

U.S. #28

1858 Jefferson, Type I

- Part of the first perforated series of US stamps

- Main usage for paying domestic portion of postage rate on overseas mail going through Britain (British Open Mail rate)

- Often used in threes to pay the postage to France

Stamp Category: Definitive

Series: 1857-61 Issue

Value: 5c

Earliest known Use: August 23, 1857

Printed by: Toppan, Carpenter & Co.

Quantity printed: 270,000 (estimate)

Format: Printed in sheets of 200 stamps, divided into vertical panes of 100 each

Printing Method: Engraving

Perforations: 15½

Color: Red Brown

Why the stamp was issued: The Act of 1855 officially introduced the use of registration of high-value letters to help deter mail theft by robbers and postal workers. The 5c Jefferson stamp was intended for the prepayment of the registration fee, but was not generally required or used for that purpose, as the fee was generally paid in cash.

The 5c denomination did pay the domestic postage portion for letters going to a foreign country if that mail was carried by British packet boats for transport. (Fees for shipping and land transport were paid by the recipient when the letter reached him or her at its destination.)

The 5c Jefferson was also commonly used in a strip of three to pay the postage to France or as a make-up rate in addition to the 10c value.

About the printing: The design is engraved on a die – a small, flat piece of steel. The design is copied to a transfer roll – a blank roll of steel. Several impressions or “reliefs” are made on the roll. The reliefs are transferred to the plate – a large, flat piece of steel from which the stamps are printed.

Types or “varieties” occur when a stamp has differences which vary from the way it was originally engraved. Foreign matter, or damage to or recutting of the plate for any reason, can cause these differences to appear on the stamps printed from it. Major and minor color varieties may also be created when a change is made to the printing ink, as is the case with the 5c Jefferson.

About the design: Thomas Jefferson’s portrait on the #28 is based on a painting by Gilbert Stuart, who also painted many portraits of George Washington.

Special Design Details: US #28 is Type I. The projections on all four sides of the stamp are complete. U.S. #28 is a perforate version of the type I imperforate 5¢ Jefferson stamp of the Series of 1851-57 (#12). The 5c perforated stamps #27, 28A and 29 are also Type I and differ from one another and #28 only in color.

Later recutting of the engraving plates to better accommodate the perforations led to the top and bottom projections being partly cut away, creating the Type II varieties of the 5c denomination (#30 and #30A).

About the 1857-61 Series: In July, 1851 – 1c, 3c, and 12c stamps were issued. The new stamps met reduced postal rates passed by act of Congress on March 3 of the same year. Further changes in postage rates appeared in the Act of March 3, 1855, leading to 10c (1855) and 5c (1856) denominations being added to the series. Perforated stamps of the same designs as the 1851-57 Imperforate Series (plus new denominations of 24c, 30c, and 90c) were issued as part of the Series of 1857-61, the first perforated U.S. stamps.

The new series’ designs were reproduced from the imperforate plates of 1851. Because the same plates were used, the perforated stamp types don’t differ much from the corresponding imperforate stamps. The entire series (U.S. #18-39) is noted for having narrow margins. This is because the perforations took up room normally given to the designs.

History the stamp represents: #28 was part of the first series of perforated U.S. postage stamps. When the world’s first postage stamps were issued, no provision was made for separating the stamps from one another. Post office clerks and stamp users merely cut these “imperforates” apart with scissors or tore them along the edge of a metal rule. A device was needed which would separate the stamps more easily and accurately.

In 1847, Irishman Henry Archer patented a machine that punched holes horizontally and vertically between rows of stamps. Now stamps could be separated without cutting. Perforations also enabled stamps to adhere better to envelopes. Archer sold his invention to the British Treasury in 1853. That same year, Great Britain produced its first perforated stamps. It wasn’t long before the US decided to make use of the new method of producing stamps with perforations, resulting in the Series of 1857-61.