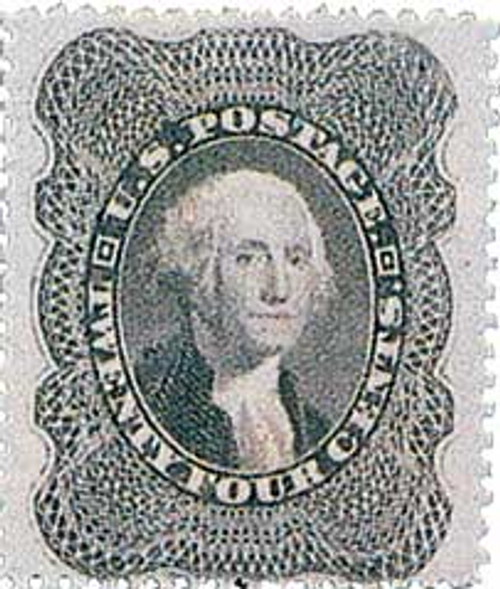

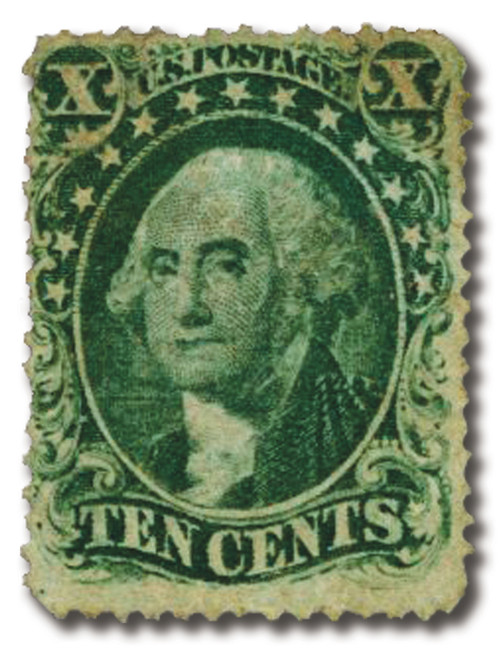

# 37 - 1860 24c Washington, perf 15

U.S. #37

1860 Washington

- Part of the first perforated series of US stamps

- Generally used for letters to Great Britain and to cover higher postal rates, in combination with other stamps, for heavier packages

Stamp Category: Definitive

Series: 1857-61 Issue

Value: 24c

Earliest Documented Use: July 7, 1860

Printed by: Toppan, Carpenter & Co.

Quantity printed: 736,000 (estimate)

Format: Printed in sheets of 200 stamps, divided into vertical panes of 100 each

Printing Method: Engraving

Perforations: 15½

Color: Gray lilac

Why the stamp was issued: The Act of April, 1855 increased the rate for any domestic letter weighing up to one-half ounce and sent over 3000 miles from six to ten cents. The rate increase helped pay for the cost of building railroads and transporting the mail such a great distance across the continent. Many of the stamps were used to frank letters going to and from to California. The 24c issue was most often used on letters up to a half ounce to Great Britain. It was also used along with stamps of other denominations to pay a higher postal rate on packages.

About the printing: The design is engraved on a die – a small, flat piece of steel. The design is copied to a transfer roll – a blank roll of steel. Several impressions or “reliefs” are made on the roll. The reliefs are transferred to the plate – a large, flat piece of steel from which the stamps are printed.

About the design: The image of George Washington on #37 is based on a painting by Gilbert Stuart, who created many portraits of the first president.

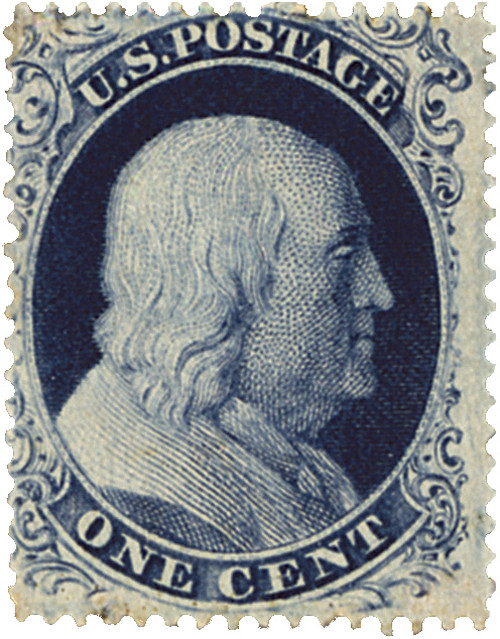

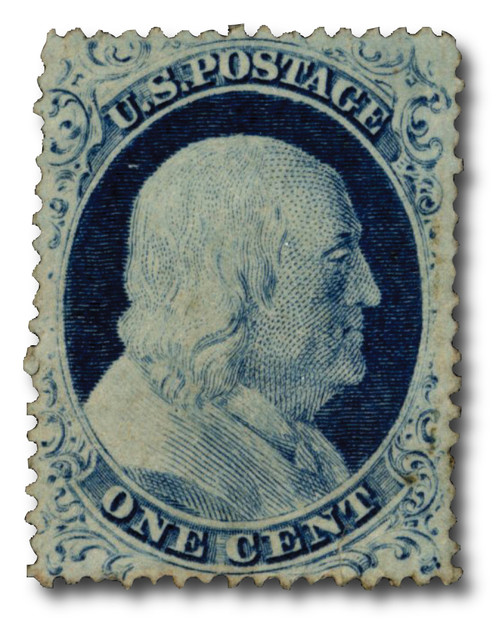

About the 1857-61 Series: In July, 1851 – 1c, 3c, and 12c stamps were issued. The new stamps met reduced postal rates passed by act of Congress on March 3 of the same year. Further changes in postage rates appeared in the Act of March 3, 1855, leading to 10c (1855) and 5c (1856) denominations being added to the series. Stamps of the same designs as the 1851-57 Imperforate Series (plus new denominations of 24c, 30c, and 90c) were issued as part of the Series of 1857-61, the first perforated U.S. stamps. The entire series is known for having narrow margins. This is because the perforations took up room normally given to the designs.

History the stamp represents: #37 was part of the first series of perforated U.S. postage stamps. When the world’s first postage stamps were issued, no provision was made for separating the stamps from one another. Post office clerks and stamp users merely cut these “imperforates” apart with scissors or tore them along the edge of a metal rule. A device was needed which would separate the stamps more easily and accurately.

In 1847, Irishman Henry Archer patented a machine that punched holes horizontally and vertically between rows of stamps. Now stamps could be separated without cutting. Perforations also enabled stamps to adhere better to envelopes. Archer sold his invention to the British Treasury in 1853. That same year, Great Britain produced its first perforated stamps. It wasn’t long before the U.S. decided to make use of the new method of producing stamps with perforations, resulting in the Series of 1857-61.

U.S. #37

1860 Washington

- Part of the first perforated series of US stamps

- Generally used for letters to Great Britain and to cover higher postal rates, in combination with other stamps, for heavier packages

Stamp Category: Definitive

Series: 1857-61 Issue

Value: 24c

Earliest Documented Use: July 7, 1860

Printed by: Toppan, Carpenter & Co.

Quantity printed: 736,000 (estimate)

Format: Printed in sheets of 200 stamps, divided into vertical panes of 100 each

Printing Method: Engraving

Perforations: 15½

Color: Gray lilac

Why the stamp was issued: The Act of April, 1855 increased the rate for any domestic letter weighing up to one-half ounce and sent over 3000 miles from six to ten cents. The rate increase helped pay for the cost of building railroads and transporting the mail such a great distance across the continent. Many of the stamps were used to frank letters going to and from to California. The 24c issue was most often used on letters up to a half ounce to Great Britain. It was also used along with stamps of other denominations to pay a higher postal rate on packages.

About the printing: The design is engraved on a die – a small, flat piece of steel. The design is copied to a transfer roll – a blank roll of steel. Several impressions or “reliefs” are made on the roll. The reliefs are transferred to the plate – a large, flat piece of steel from which the stamps are printed.

About the design: The image of George Washington on #37 is based on a painting by Gilbert Stuart, who created many portraits of the first president.

About the 1857-61 Series: In July, 1851 – 1c, 3c, and 12c stamps were issued. The new stamps met reduced postal rates passed by act of Congress on March 3 of the same year. Further changes in postage rates appeared in the Act of March 3, 1855, leading to 10c (1855) and 5c (1856) denominations being added to the series. Stamps of the same designs as the 1851-57 Imperforate Series (plus new denominations of 24c, 30c, and 90c) were issued as part of the Series of 1857-61, the first perforated U.S. stamps. The entire series is known for having narrow margins. This is because the perforations took up room normally given to the designs.

History the stamp represents: #37 was part of the first series of perforated U.S. postage stamps. When the world’s first postage stamps were issued, no provision was made for separating the stamps from one another. Post office clerks and stamp users merely cut these “imperforates” apart with scissors or tore them along the edge of a metal rule. A device was needed which would separate the stamps more easily and accurately.

In 1847, Irishman Henry Archer patented a machine that punched holes horizontally and vertically between rows of stamps. Now stamps could be separated without cutting. Perforations also enabled stamps to adhere better to envelopes. Archer sold his invention to the British Treasury in 1853. That same year, Great Britain produced its first perforated stamps. It wasn’t long before the U.S. decided to make use of the new method of producing stamps with perforations, resulting in the Series of 1857-61.