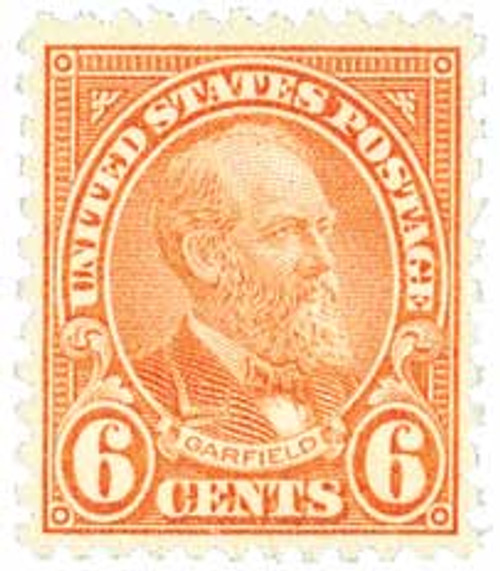

1927 8c Grant, olive green

# 640 - 1927 8c Grant, olive green

MSRP:

Was:

Now:

$0.35 - $505.00

(You save

)

Write a Review

Write a Review

640 - 1927 8c Grant, olive green

| Image | Condition | Price | Qty | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mint Plate Block

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 27.50

|

$ 27.50 |

|

0

|

|

Mint Stamp(s)

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 4.95

|

$ 4.95 |

|

1

|

|

Mint Stamp(s)

Fine

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 6.00

|

$ 6.00 |

|

2

|

|

Mint Sheet(s)

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 505.00

|

$ 505.00 |

|

3

|

|

Mint Stamp(s)

Fine, Never Hinged

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 7.25

|

$ 7.25 |

|

4

|

|

Mint Stamp(s)

Very Fine

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 7.25

|

$ 7.25 |

|

5

|

|

Mint Stamp(s)

Very Fine, Never Hinged

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 8.50

|

$ 8.50 |

|

6

|

|

Used Single Stamp(s)

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 0.35

|

$ 0.35 |

|

7

|

|

Used Single Stamp(s)

Fine

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 1.00

|

$ 1.00 |

|

8

|

|

Unused Stamp(s)

small flaws

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Free with 1,050 Points

$ 3.50

|

$ 3.50 |

|

9

|

|

Used Stamp(s)

small flaws

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 0.35

|

$ 0.35 |

|

10

|

|

Unused Plate Block

small flaws

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 19.00

|

$ 19.00 |

|

11

|

Mounts - Click Here

| Mount | Price | Qty |

|---|

U.S. #640

1926-28 Rotary Stamps

8¢ Ulysses S. Grant

1926-28 Rotary Stamps

8¢ Ulysses S. Grant

First Day of Issue: June 10, 1927

First City: Washington, D.C.

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Perforation: 11 x 10 ½

Color: Olive green

First City: Washington, D.C.

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Perforation: 11 x 10 ½

Color: Olive green

The portrait of Ulysses S. Grant on U.S. #640 came from a photograph by renowned Civil War photographer Matthew Brady. While the 8¢ stamp had many uses at the time, it saw an increase in demand in 1932 when the Airmail letter rate was raised from 5¢ to 8¢.

U.S. #640

1926-28 Rotary Stamps

8¢ Ulysses S. Grant

1926-28 Rotary Stamps

8¢ Ulysses S. Grant

First Day of Issue: June 10, 1927

First City: Washington, D.C.

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Perforation: 11 x 10 ½

Color: Olive green

First City: Washington, D.C.

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Perforation: 11 x 10 ½

Color: Olive green

The portrait of Ulysses S. Grant on U.S. #640 came from a photograph by renowned Civil War photographer Matthew Brady. While the 8¢ stamp had many uses at the time, it saw an increase in demand in 1932 when the Airmail letter rate was raised from 5¢ to 8¢.

!