1938 4c Madison, dark rose

# 808 - 1938 4c Madison, dark rose

$0.40 - $150.00

U.S. #808

1938 4¢ James Madison

Presidential Series

1938 4¢ James Madison

Presidential Series

Issue Date: July 1, 1938

First City: Washington, DC

Quantity Issued: 905,230,500

Printing Method: Rotary press

Perforations: 11 x 10 ½

Color: Red violet

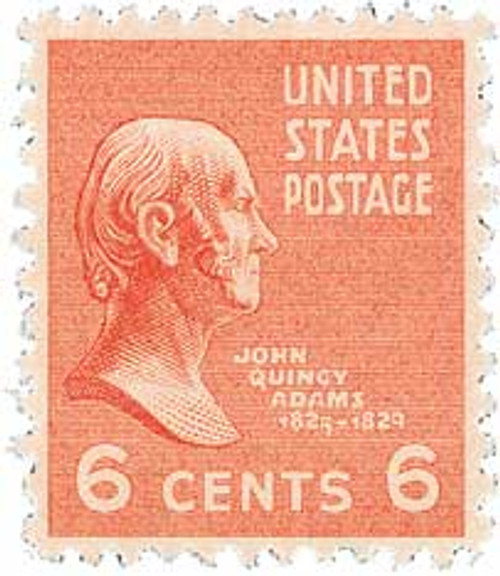

Known affectionately as the Prexies,the 1938 Presidential series is a favorite among stamp collectors.

The series was issued in response to public clamoring for a new Regular Issue series.The series that was current at the time had been in use for more than a decade. President Franklin D. Roosevelt agreed, and a contest was staged. The public was asked to submit original designs for a new series picturing all deceased U.S. Presidents. Over 1,100 sketches were submitted, many from veteran stamp collectors. Elaine Rawlinson, who had little knowledge of stamps, won the contest and collected the $500 prize. Rawlinson was the first stamp designer since the Bureau of Engraving and Printing began producing U.S. stamps who was not a government employee.

U.S. #808

1938 4¢ James Madison

Presidential Series

1938 4¢ James Madison

Presidential Series

Issue Date: July 1, 1938

First City: Washington, DC

Quantity Issued: 905,230,500

Printing Method: Rotary press

Perforations: 11 x 10 ½

Color: Red violet

Known affectionately as the Prexies,the 1938 Presidential series is a favorite among stamp collectors.

The series was issued in response to public clamoring for a new Regular Issue series.The series that was current at the time had been in use for more than a decade. President Franklin D. Roosevelt agreed, and a contest was staged. The public was asked to submit original designs for a new series picturing all deceased U.S. Presidents. Over 1,100 sketches were submitted, many from veteran stamp collectors. Elaine Rawlinson, who had little knowledge of stamps, won the contest and collected the $500 prize. Rawlinson was the first stamp designer since the Bureau of Engraving and Printing began producing U.S. stamps who was not a government employee.