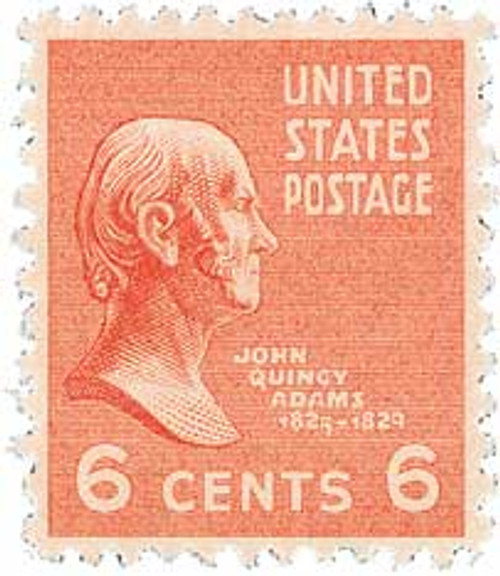

# 818 - 1938 13c Fillmore, green

Write a Review

818 - 1938 13c Fillmore, green

| Image | Condition | Price | Qty | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mint Plate Block

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 12.75

|

$ 12.75 |

|

0

|

|

Mint Stamp(s)

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 2.75

|

$ 2.75 |

|

1

|

|

Mint Stamp(s)

Fine

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 3.25

|

$ 3.25 |

|

2

|

|

Mint Sheet(s)

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 275.00

|

$ 275.00 |

|

3

|

|

Mint Stamp(s)

Fine, Never Hinged

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 4.00

|

$ 4.00 |

|

4

|

|

Mint Stamp(s)

Very Fine

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 3.95

|

$ 3.95 |

|

5

|

|

Mint Stamp(s)

Very Fine, Never Hinged

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 4.75

|

$ 4.75 |

|

6

|

|

Used Single Stamp(s)

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 0.40

|

$ 0.40 |

|

7

|

|

Used Single Stamp(s)

Fine

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 1.05

|

$ 1.05 |

|

8

|

|

Used Single Stamp(s)

Very Fine

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 1.35

|

$ 1.35 |

|

9

|

|

Unused Stamp(s)

small flaws

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Free with 420 Points

$ 1.75

|

$ 1.75 |

|

10

|

|

Used Stamp(s)

small flaws

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 0.35

|

$ 0.35 |

|

11

|

| Mount | Price | Qty |

|---|

1938 13¢ Millard Fillmore

Presidential Series

Issue Date: September 22, 1938

First City: Washington, DC

Quantity Issued: 293,750,100

Printing Method: Rotary press

Perforations: 11 x 10 ½

Color: Blue green

Birth Of President Millard Fillmore

Americas 13th president, Millard Fillmore, was born on January 7, 1800, in Moravia, New York.

Born three weeks after the death of George Washington, Millard Fillmore was Americas first President to be born after the death of a former President, and the first born in the 19th Century. With few opportunities available, at the age of 14 Fillmores father apprenticed him to a cloth maker in Sparta, New York. Tired of working under poor conditions, Fillmore bought his freedom and walked 100 miles to get home.

1938 13¢ Millard Fillmore

Presidential Series

Issue Date: September 22, 1938

First City: Washington, DC

Quantity Issued: 293,750,100

Printing Method: Rotary press

Perforations: 11 x 10 ½

Color: Blue green

Birth Of President Millard Fillmore

Americas 13th president, Millard Fillmore, was born on January 7, 1800, in Moravia, New York.

Born three weeks after the death of George Washington, Millard Fillmore was Americas first President to be born after the death of a former President, and the first born in the 19th Century. With few opportunities available, at the age of 14 Fillmores father apprenticed him to a cloth maker in Sparta, New York. Tired of working under poor conditions, Fillmore bought his freedom and walked 100 miles to get home.