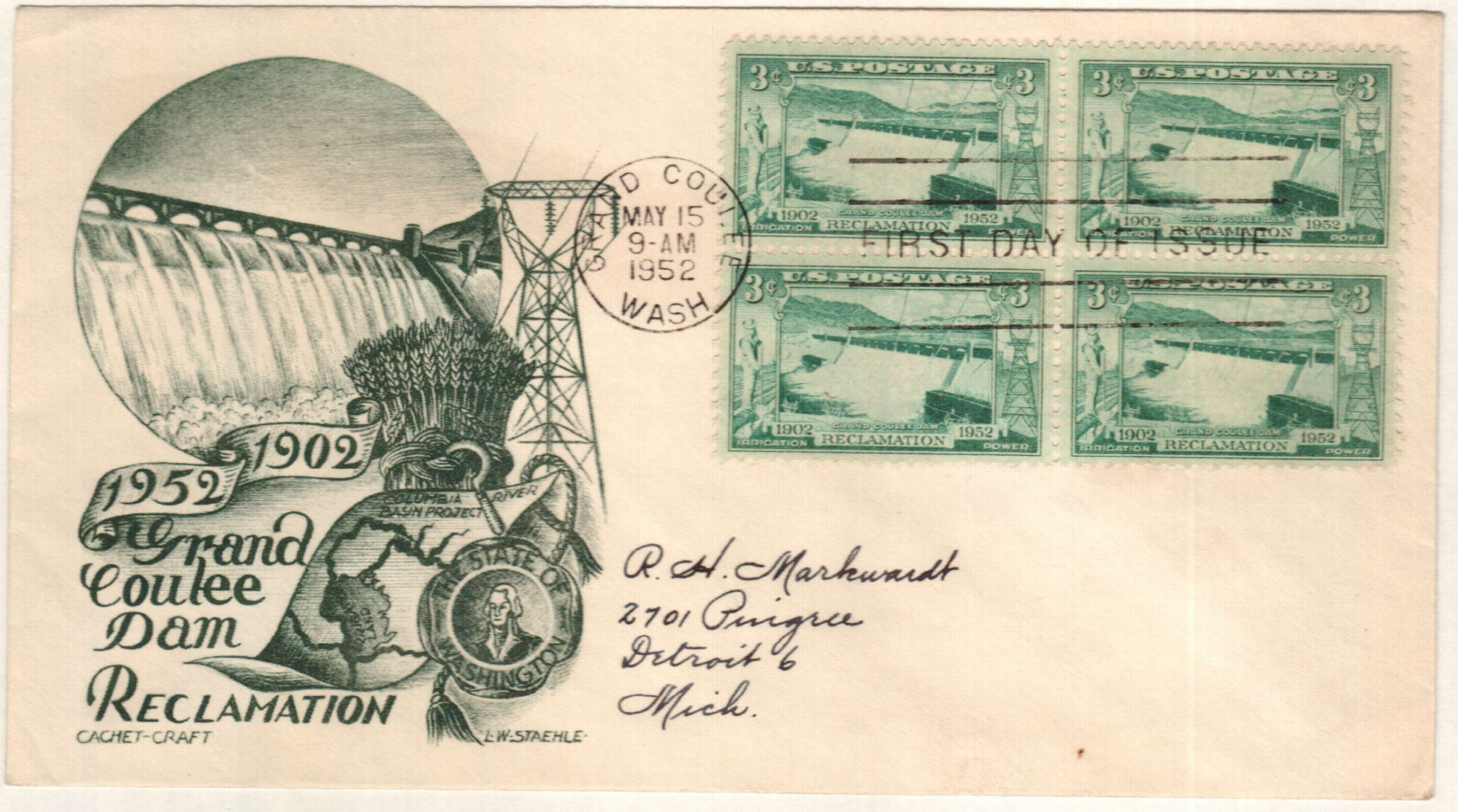

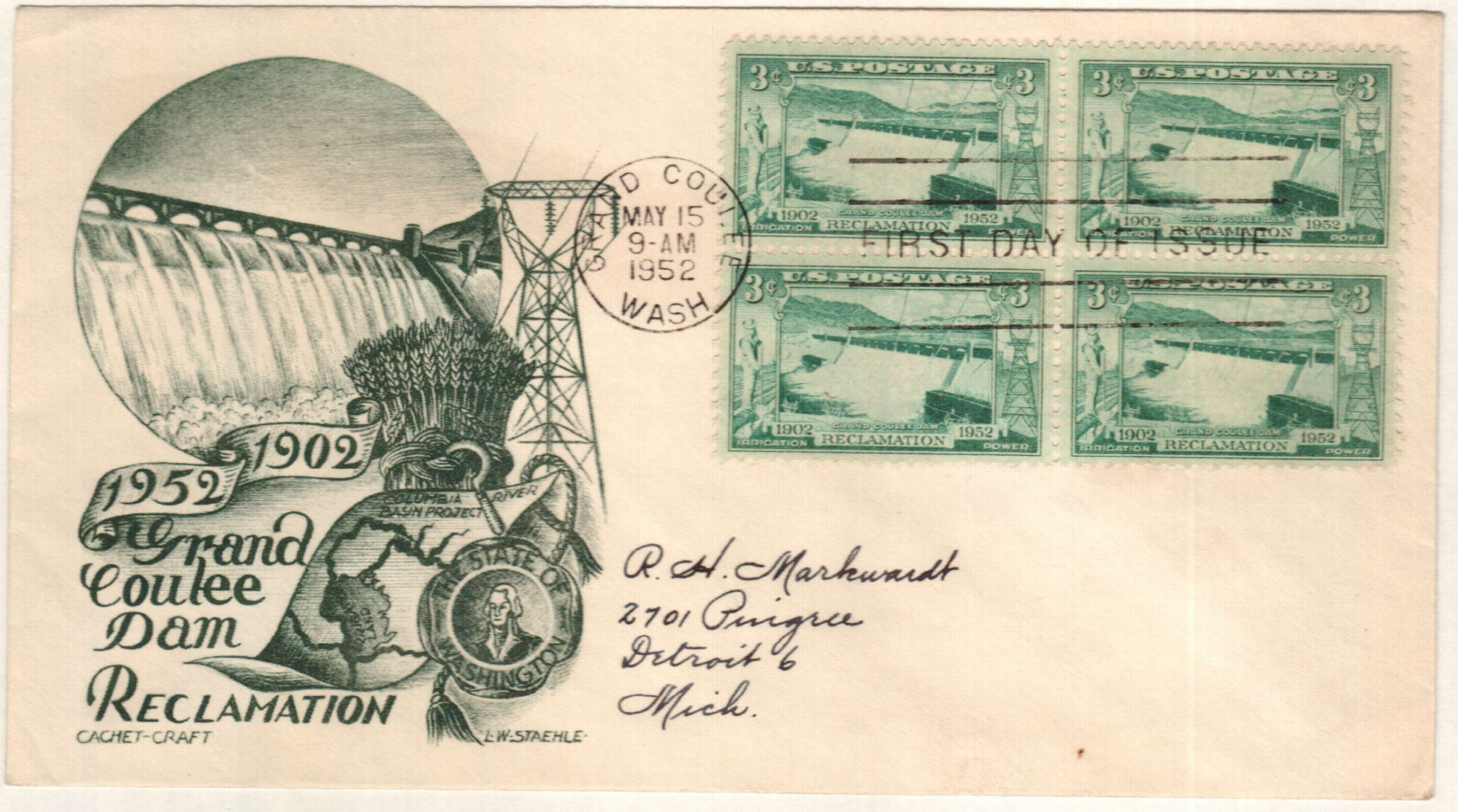

# 1009 - 1952 3¢ Grand Coulee Dam

3¢ Grand Coulee Dam

City: Grand Coulee, WA

Quantity: 114,540,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Perforations: 11 x 10½

Color: Blue green

The Grand Coulee Dam

The Grand Coulee is a very old riverbed on the Columbia Plateau. As early as 1892, there were discussions of a possible plan to build a 1,000-foot dam across the Columbia River. However, that would have meant a reservoir would extend into Canada, which violated treaties.

In the early 1900s, talks of a similar project were renewed by the Bureau of Reclamation, which sought to pump water from the Columbia River to irrigate areas in central Washington. They attempted to raise money for the project but Washington citizens voted against it.

Then in 1917, a Washington lawyer named William M. Clapp suggested that the Columbia be dammed just below the Grand Coulee. He suggested that a concrete dam could flood the plateau, just as the ice had centuries before. James O’Sullivan and Rufus Woods joined in the campaign for the Grand Coulee Dam. Woods was a newspaper publisher and promoted the idea in The Wenatchee World. He wrote, “Such a power if developed would operate railroads, factories, mines, irrigation pumps, furnish heat and light in such measure that all in all it would be the most unique, the most interesting, and the most remarkable development of both irrigation and power in this age of industrial and scientific miracles.”

By 1918, there was widespread public support for the project. However, they soon divided into two groups, the pumpers and the ditchers. The pumpers supported a dam with pumps to lift water into the Grand Coulee, from where it would follow canals and pipes to irrigate farmland. The ditchers wanted to divert the water through a gravity canal. Many of the pumpers believed the ditchers were trying to hold a monopoly on electric power.

The ditchers took several steps to support their cause, including getting a preliminary permit to build a dam that would block construction of the Coulee Dam. They also got the support of President Warren G. Harding, but he died a month later. Calvin Coolidge had little interest initially but ultimately opposed the project after listening to concerns that increased irrigation would create more crops and poor prices.

Then in 1925, Congress called on the US Army Corps of Engineers to study the Columbia River. After extensive study, they suggested the Grand Coulee Dam and nine others on the river in 1932. The report said the construction could be paid for by the electricity sales generated by the dam. While some still opposed the project, President Franklin Roosevelt ultimately approved.

Construction officially began on July 16, 1933, as a crowd of 3,000 spectators watched the driving of the first stake. Roosevelt visited the site the following year and then approved that it be upgraded to a high dam at 500-feet tall. After seven years of construction, the dam first began operations on March 22, 1941, when its first large generators began producing power. The two generators sent about 10,000 kilowatts of electricity to the Bonneville Power Administrations transmission network.

Thousands of people came out to watch the start of the generators. The day’s events also included speeches and music. Roosevelt, who didn’t attend, sent a telegram saying, “This project will have served in two emergencies. It served to provide much useful employment at a time eight years ago when it was important that we find at once a means of avoiding complete economic stagnation, and it will serve now to provide the power to make aluminum for airplanes and otherwise to speed our protective arms.”

Work on the dam would continue for another two years, being officially completed on January 31, 1943.

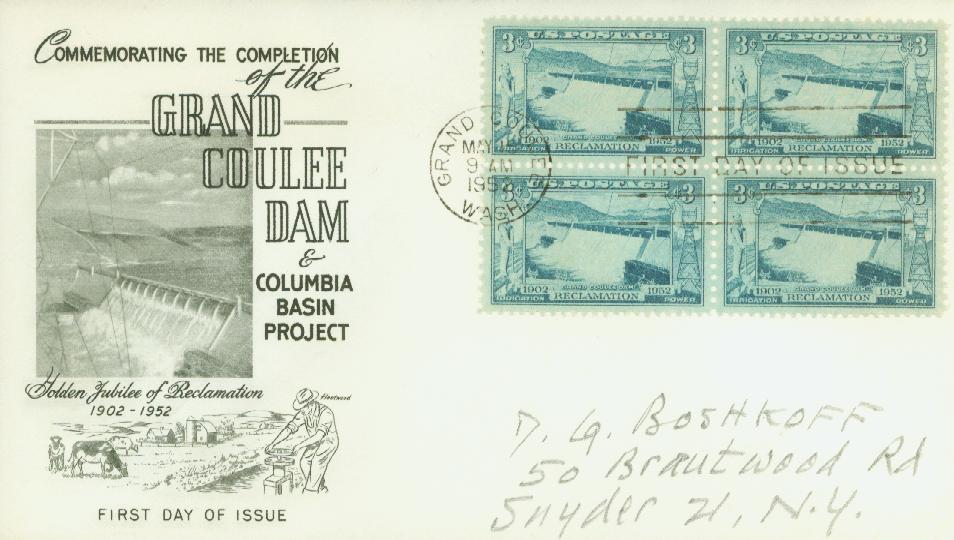

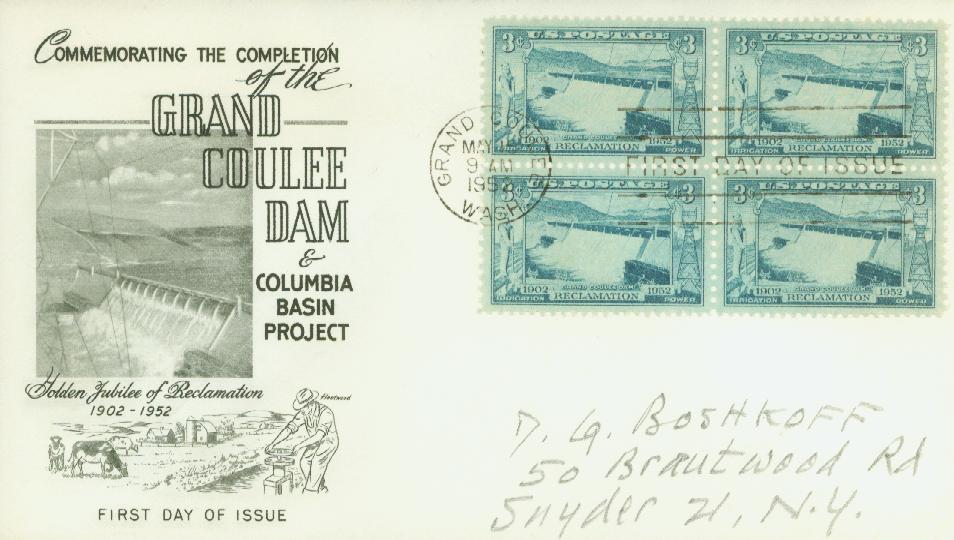

3¢ Grand Coulee Dam

City: Grand Coulee, WA

Quantity: 114,540,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Perforations: 11 x 10½

Color: Blue green

The Grand Coulee Dam

The Grand Coulee is a very old riverbed on the Columbia Plateau. As early as 1892, there were discussions of a possible plan to build a 1,000-foot dam across the Columbia River. However, that would have meant a reservoir would extend into Canada, which violated treaties.

In the early 1900s, talks of a similar project were renewed by the Bureau of Reclamation, which sought to pump water from the Columbia River to irrigate areas in central Washington. They attempted to raise money for the project but Washington citizens voted against it.

Then in 1917, a Washington lawyer named William M. Clapp suggested that the Columbia be dammed just below the Grand Coulee. He suggested that a concrete dam could flood the plateau, just as the ice had centuries before. James O’Sullivan and Rufus Woods joined in the campaign for the Grand Coulee Dam. Woods was a newspaper publisher and promoted the idea in The Wenatchee World. He wrote, “Such a power if developed would operate railroads, factories, mines, irrigation pumps, furnish heat and light in such measure that all in all it would be the most unique, the most interesting, and the most remarkable development of both irrigation and power in this age of industrial and scientific miracles.”

By 1918, there was widespread public support for the project. However, they soon divided into two groups, the pumpers and the ditchers. The pumpers supported a dam with pumps to lift water into the Grand Coulee, from where it would follow canals and pipes to irrigate farmland. The ditchers wanted to divert the water through a gravity canal. Many of the pumpers believed the ditchers were trying to hold a monopoly on electric power.

The ditchers took several steps to support their cause, including getting a preliminary permit to build a dam that would block construction of the Coulee Dam. They also got the support of President Warren G. Harding, but he died a month later. Calvin Coolidge had little interest initially but ultimately opposed the project after listening to concerns that increased irrigation would create more crops and poor prices.

Then in 1925, Congress called on the US Army Corps of Engineers to study the Columbia River. After extensive study, they suggested the Grand Coulee Dam and nine others on the river in 1932. The report said the construction could be paid for by the electricity sales generated by the dam. While some still opposed the project, President Franklin Roosevelt ultimately approved.

Construction officially began on July 16, 1933, as a crowd of 3,000 spectators watched the driving of the first stake. Roosevelt visited the site the following year and then approved that it be upgraded to a high dam at 500-feet tall. After seven years of construction, the dam first began operations on March 22, 1941, when its first large generators began producing power. The two generators sent about 10,000 kilowatts of electricity to the Bonneville Power Administrations transmission network.

Thousands of people came out to watch the start of the generators. The day’s events also included speeches and music. Roosevelt, who didn’t attend, sent a telegram saying, “This project will have served in two emergencies. It served to provide much useful employment at a time eight years ago when it was important that we find at once a means of avoiding complete economic stagnation, and it will serve now to provide the power to make aluminum for airplanes and otherwise to speed our protective arms.”

Work on the dam would continue for another two years, being officially completed on January 31, 1943.