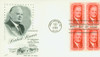

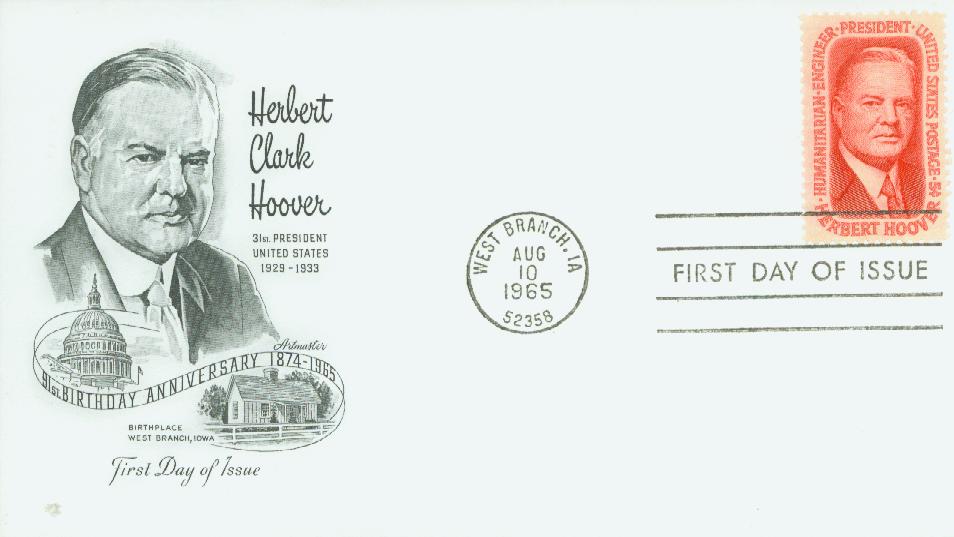

# 1269 - 1965 5c Herbert Hoover

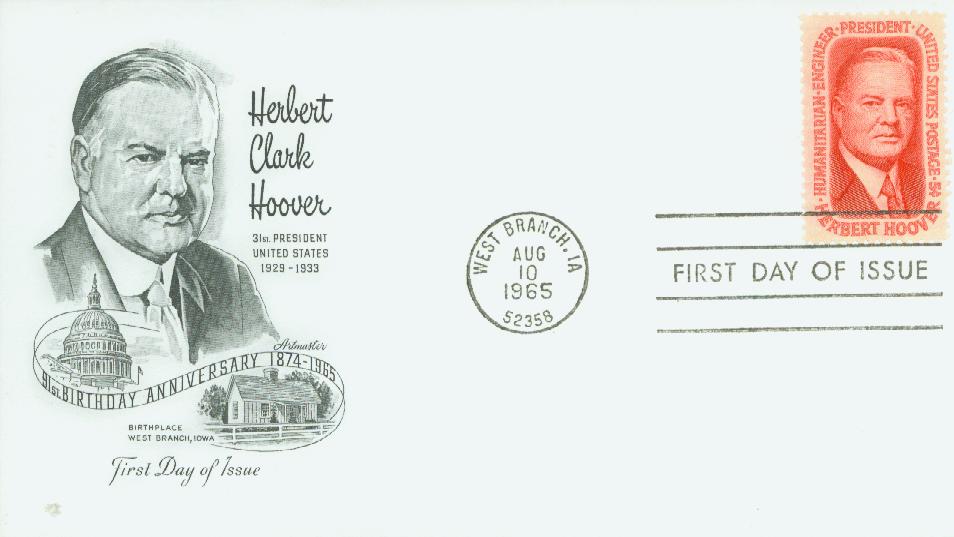

5¢ Herbert Hoover

City: West Branch, IA

Quantity: 114,840,000

Printed By: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Rotary press

Perforations: 10 ½ x 11

Color: Rose red

birth of herbert hoover

Hoover’s parents and many of their neighbors were Quakers, and their ideals of hard work, nonviolence, and community cooperation influenced Hoover’s entire life. Both parents passed away before Hoover was 10 years old, and he was sent to Oregon to live with his uncle, a doctor, and a businessman.

In 1891, Hoover was one of the first students to enroll in Stanford University in California, where he studied engineering and mining. He worked for the US Geological Survey during the summers and after his graduation.

Hoover then became a world traveler when a British mining company, Bewick, Moreing & Co, hired him. His first assignment was in Australia, where he scouted for mineral deposits, particularly gold. He was promoted to mine manager by the time he was 23 and expanded the Sons of Gwalia Mine, which became one of the richest in Australia. He was then offered a promotion in China. That move would change the direction of his life.

Hoover and his new wife settled in the port city of Tientsin, and he began his work as the chief engineer at China’s Bureau of Mines. The Boxer Rebellion erupted in 1900, as nationalists tried to drive foreigners out of the country. Hoover organized the foreign residents that were caught in the city. He helped supervise building barricades and kept residents supplied with food and water. After a month-long siege, a multinational army freed the city from the Boxers.

Later that year, the Hoovers moved to London, which became their home base when they were not traveling to mines around the world. In 1908, Hoover established his own company and eventually had investments on every continent. When he was not overseeing operations in the field, he lectured about mining. Within a few years, Hoover was a self-made man worth approximately $4 million.

The Hoovers, along with their two young sons, were in London when World War I began. About 120,000 Americans were stranded in Europe with no means to return home. Hoover assembled 500 volunteers to distribute food, clothing, and tickets for passage to the US. Within six weeks, all the displaced travelers were on their way home.

The family stayed in Europe, heading up relief efforts including the unprecedented task of feeding all the citizens of Belgium throughout the war. The Commission for Relief in Belgium collected millions of tons of food, and Hoover made sure it was distributed to the people and not taken by the German army. Over the next two years, he supervised the feeding of nine million Belgians.

When America entered the war, President Wilson asked Hoover to return to America to head the US Food Administration. He used what he had learned in Europe to run the program. Americans were asked to have meatless Mondays and wheatless Wednesdays so the soldiers would have enough to eat. It became known as “Hooverizing,” and the policies reduced consumption, avoiding the need to ration food.

After the war, Hoover continued his humanitarian efforts as head of the American Relief Administration. He was once again in charge of getting tons of food to starving people in Europe. Because of his selfless work, the New York Times named Hoover one of the “Ten Most Important Living Americans.” His popularity led to an offer to be the presidential nominee by both parties in the 1920 election, but he declined to run. Instead, he supported the republicans’ candidate, Warren Harding, who won the election that November and rewarded Hoover with a Cabinet position.

Hoover became secretary of the recently formed Commerce Department. It was considered a minor position, but it grew under Hoover’s guidance. His manufacturing-code programs set standards for sizes of everyday products, making it easier for consumers to buy replacement parts. He also expanded foreign markets for American-made goods. Hoover’s conferences with auto manufacturers and radio executives forged strong relationships between business and government and led to voluntary regulations of the industries. Hoover’s “Own Your Own Home” campaign encouraged banks to offer long-term mortgages to increase homeownership. Many historians consider Hoover the best secretary of commerce in US history because of the work he did to define the post.

While serving in his Cabinet position, Hoover returned to the role of relief organizer after a flood devastated the Mississippi River Valley in 1927. The front-page news coverage he received for his work made Hoover a household name. In 1928, he was selected as the republican presidential candidate on the first ballot.

Hoover won by a landslide in his first time running for public office. His term in office largely revolved around dealing with the stock market crash of 1929. Hoover felt if communities and the nation worked together, the country would pull through successfully without government intervention. He met with top business leaders from around the country to encourage them not to lower workers’ wages. Hoover also urged state and local governments to expand public works projects to create more jobs.

Most of Europe was still trying to recover from the Great War when the economic disaster struck. Hoover suspended the payment of war debts to the US because many of the nations could not pay. The decreased revenue meant the federal government had less to spend to help those in need.

Hoover was hesitant to use Federal money for social welfare programs, fearing it would lead the country toward socialism. As his term in office progressed, he became the scapegoat for the nation’s condition. Cardboard towns, known as “Hoovervilles,” developed, often near garbage dumps where people could scrounge for food.

In 1932, Hoover ran for re-election, defending his record and attacking the plans of his opponent. Franklin D. Roosevelt, the democratic candidate, was confident and optimistic. He promised Americans a “New Deal.” That November, voters overwhelmingly chose Roosevelt.

Hoover returned to his home in California when his term in office was over and continued the work he had begun before his election. Much of his attention went toward the Hoover Library on War, Revolution, and Peace, housed at his alma mater, Stanford University.

During World War II, Hoover returned to his previous role as an organizer of relief services. He became head of the Commission for Polish Relief. After the war, nations all over Europe and Asia were experiencing famine, and starvation was a real concern. President Harry Truman asked Hoover to act as honorary chairman of the Famine Emergency Commission. At 71 years old, he embarked on a world tour to survey the extent of the needs, visiting 25 countries in two months. After filing his report with the commission, Hoover traveled to countries with surplus food stores, convincing them to contribute to relief efforts.

Truman called on Hoover again in 1947 to chair the Commission on Organization of the executive branch of the government. The goal was to improve the efficiency of the executive branch. In 1949, the commission presented 273 recommendations to Congress. This led to the Reorganization Act of 1949.

Hoover retired to private life again, where he spent his time writing and overseeing the Hoover Institute. He was also chairman of the Boys’ Club of America for eight years. After living a life filled with financial success, world travel, and public service, Herbert Hoover died on October 20, 1964. At the time, he had the longest retirement of any former president and was the second longest-lived president in US history.

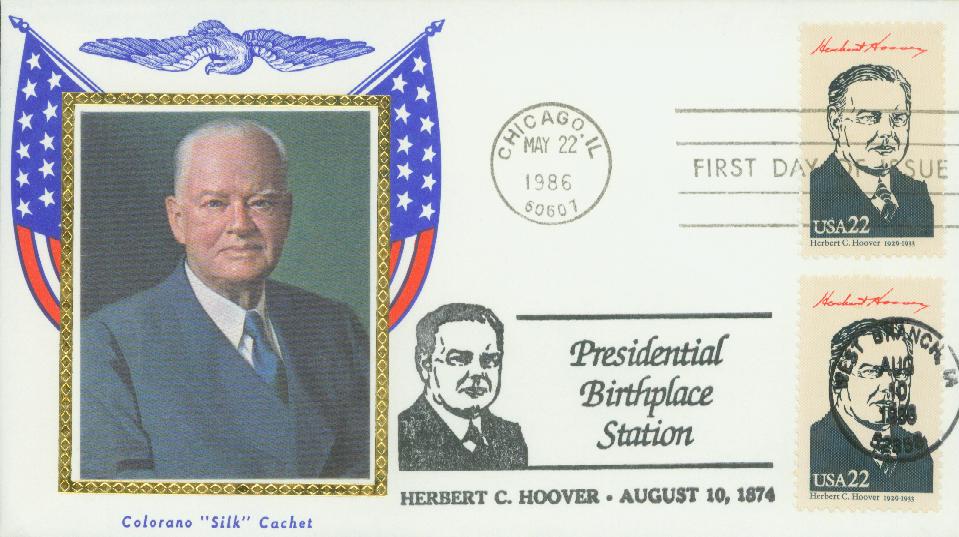

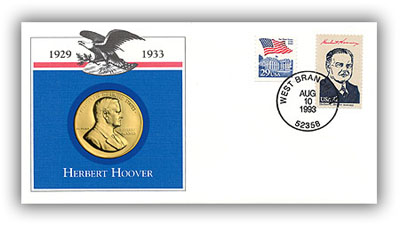

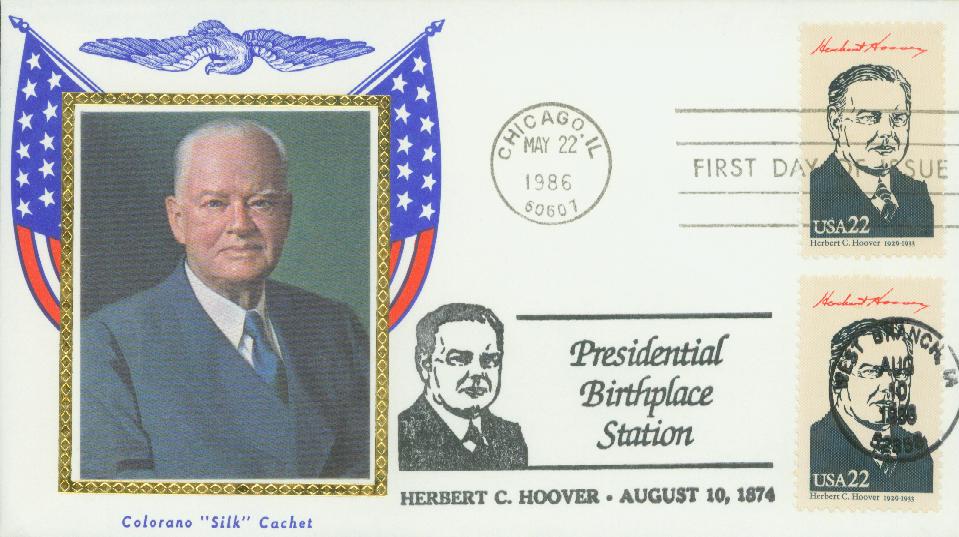

5¢ Herbert Hoover

City: West Branch, IA

Quantity: 114,840,000

Printed By: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Rotary press

Perforations: 10 ½ x 11

Color: Rose red

birth of herbert hoover

Hoover’s parents and many of their neighbors were Quakers, and their ideals of hard work, nonviolence, and community cooperation influenced Hoover’s entire life. Both parents passed away before Hoover was 10 years old, and he was sent to Oregon to live with his uncle, a doctor, and a businessman.

In 1891, Hoover was one of the first students to enroll in Stanford University in California, where he studied engineering and mining. He worked for the US Geological Survey during the summers and after his graduation.

Hoover then became a world traveler when a British mining company, Bewick, Moreing & Co, hired him. His first assignment was in Australia, where he scouted for mineral deposits, particularly gold. He was promoted to mine manager by the time he was 23 and expanded the Sons of Gwalia Mine, which became one of the richest in Australia. He was then offered a promotion in China. That move would change the direction of his life.

Hoover and his new wife settled in the port city of Tientsin, and he began his work as the chief engineer at China’s Bureau of Mines. The Boxer Rebellion erupted in 1900, as nationalists tried to drive foreigners out of the country. Hoover organized the foreign residents that were caught in the city. He helped supervise building barricades and kept residents supplied with food and water. After a month-long siege, a multinational army freed the city from the Boxers.

Later that year, the Hoovers moved to London, which became their home base when they were not traveling to mines around the world. In 1908, Hoover established his own company and eventually had investments on every continent. When he was not overseeing operations in the field, he lectured about mining. Within a few years, Hoover was a self-made man worth approximately $4 million.

The Hoovers, along with their two young sons, were in London when World War I began. About 120,000 Americans were stranded in Europe with no means to return home. Hoover assembled 500 volunteers to distribute food, clothing, and tickets for passage to the US. Within six weeks, all the displaced travelers were on their way home.

The family stayed in Europe, heading up relief efforts including the unprecedented task of feeding all the citizens of Belgium throughout the war. The Commission for Relief in Belgium collected millions of tons of food, and Hoover made sure it was distributed to the people and not taken by the German army. Over the next two years, he supervised the feeding of nine million Belgians.

When America entered the war, President Wilson asked Hoover to return to America to head the US Food Administration. He used what he had learned in Europe to run the program. Americans were asked to have meatless Mondays and wheatless Wednesdays so the soldiers would have enough to eat. It became known as “Hooverizing,” and the policies reduced consumption, avoiding the need to ration food.

After the war, Hoover continued his humanitarian efforts as head of the American Relief Administration. He was once again in charge of getting tons of food to starving people in Europe. Because of his selfless work, the New York Times named Hoover one of the “Ten Most Important Living Americans.” His popularity led to an offer to be the presidential nominee by both parties in the 1920 election, but he declined to run. Instead, he supported the republicans’ candidate, Warren Harding, who won the election that November and rewarded Hoover with a Cabinet position.

Hoover became secretary of the recently formed Commerce Department. It was considered a minor position, but it grew under Hoover’s guidance. His manufacturing-code programs set standards for sizes of everyday products, making it easier for consumers to buy replacement parts. He also expanded foreign markets for American-made goods. Hoover’s conferences with auto manufacturers and radio executives forged strong relationships between business and government and led to voluntary regulations of the industries. Hoover’s “Own Your Own Home” campaign encouraged banks to offer long-term mortgages to increase homeownership. Many historians consider Hoover the best secretary of commerce in US history because of the work he did to define the post.

While serving in his Cabinet position, Hoover returned to the role of relief organizer after a flood devastated the Mississippi River Valley in 1927. The front-page news coverage he received for his work made Hoover a household name. In 1928, he was selected as the republican presidential candidate on the first ballot.

Hoover won by a landslide in his first time running for public office. His term in office largely revolved around dealing with the stock market crash of 1929. Hoover felt if communities and the nation worked together, the country would pull through successfully without government intervention. He met with top business leaders from around the country to encourage them not to lower workers’ wages. Hoover also urged state and local governments to expand public works projects to create more jobs.

Most of Europe was still trying to recover from the Great War when the economic disaster struck. Hoover suspended the payment of war debts to the US because many of the nations could not pay. The decreased revenue meant the federal government had less to spend to help those in need.

Hoover was hesitant to use Federal money for social welfare programs, fearing it would lead the country toward socialism. As his term in office progressed, he became the scapegoat for the nation’s condition. Cardboard towns, known as “Hoovervilles,” developed, often near garbage dumps where people could scrounge for food.

In 1932, Hoover ran for re-election, defending his record and attacking the plans of his opponent. Franklin D. Roosevelt, the democratic candidate, was confident and optimistic. He promised Americans a “New Deal.” That November, voters overwhelmingly chose Roosevelt.

Hoover returned to his home in California when his term in office was over and continued the work he had begun before his election. Much of his attention went toward the Hoover Library on War, Revolution, and Peace, housed at his alma mater, Stanford University.

During World War II, Hoover returned to his previous role as an organizer of relief services. He became head of the Commission for Polish Relief. After the war, nations all over Europe and Asia were experiencing famine, and starvation was a real concern. President Harry Truman asked Hoover to act as honorary chairman of the Famine Emergency Commission. At 71 years old, he embarked on a world tour to survey the extent of the needs, visiting 25 countries in two months. After filing his report with the commission, Hoover traveled to countries with surplus food stores, convincing them to contribute to relief efforts.

Truman called on Hoover again in 1947 to chair the Commission on Organization of the executive branch of the government. The goal was to improve the efficiency of the executive branch. In 1949, the commission presented 273 recommendations to Congress. This led to the Reorganization Act of 1949.

Hoover retired to private life again, where he spent his time writing and overseeing the Hoover Institute. He was also chairman of the Boys’ Club of America for eight years. After living a life filled with financial success, world travel, and public service, Herbert Hoover died on October 20, 1964. At the time, he had the longest retirement of any former president and was the second longest-lived president in US history.