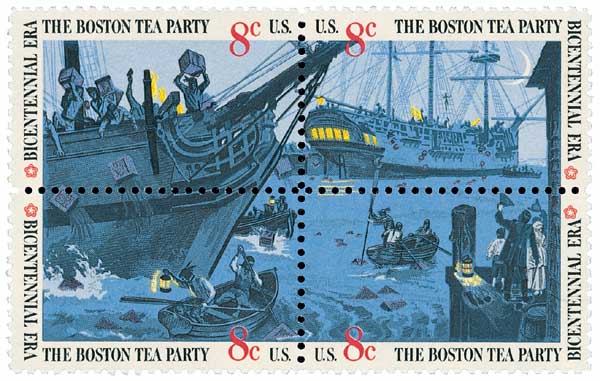

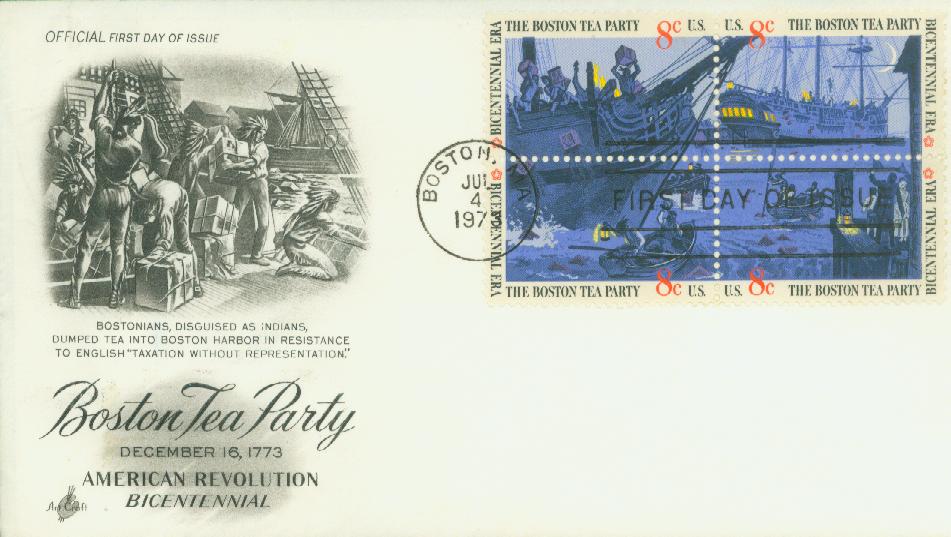

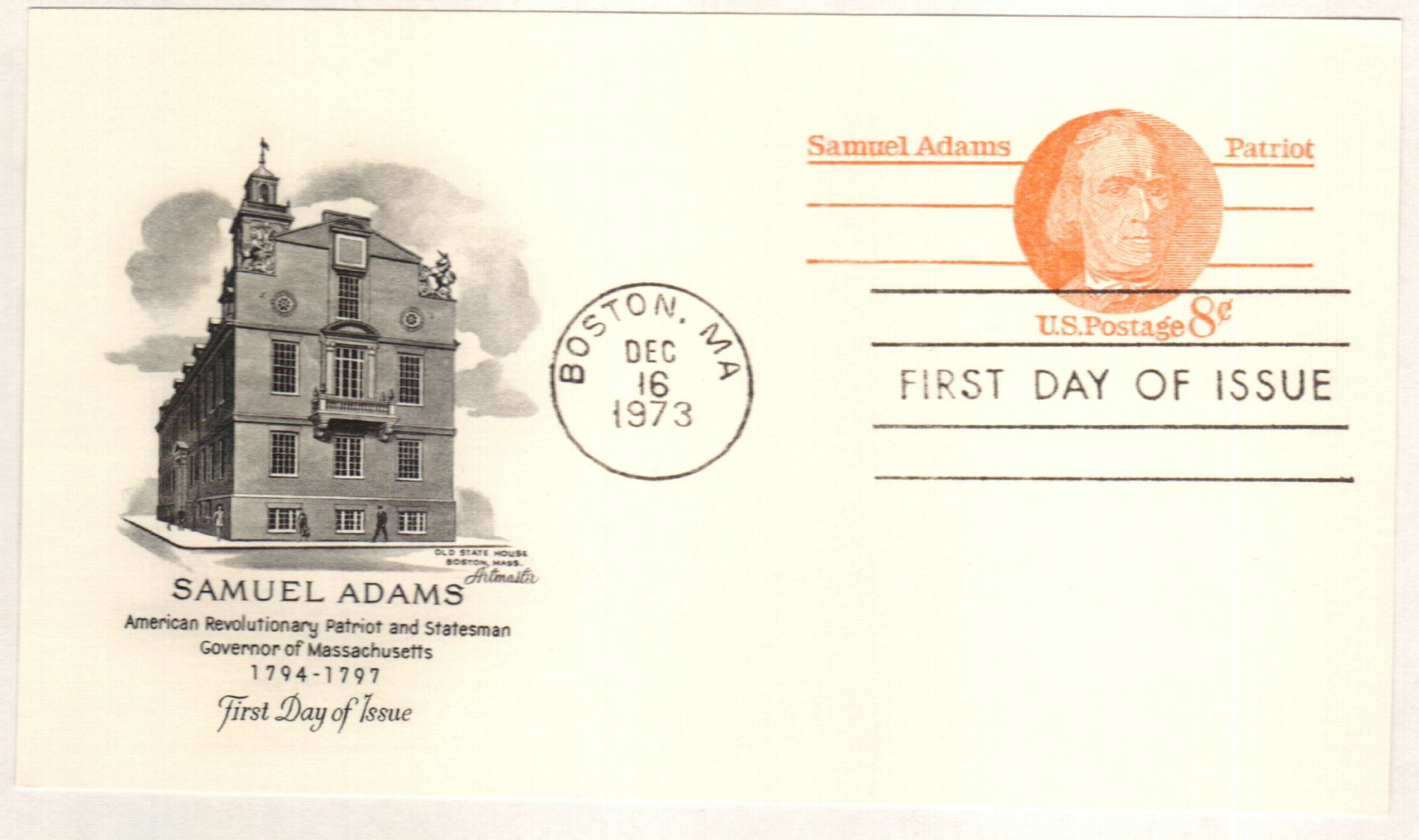

# 1480-83 - 1973 8c Boston Tea Party

Set of 4

Colonists Revolt With Boston Tea Party

On December 16, 1773, a group of Massachusetts colonists known as the Sons of Liberty staged a dramatic protest against British taxes – the famed Boston Tea Party.

The French and Indian War left Britain in debt. So taxes were levied on the New World colonies, which enraged colonists as they had no say in government. The slogan, “No taxation without representation,” became popular in Massachusetts and protests were staged. In 1770, British soldiers fired on a group of angry patriots, killing five of them. The Boston Massacre, as it came to be known, sparked public sentiment against the British.

Britain continued to impose new tea taxes on the colonies. The colonists weren’t simply upset at the taxes themselves, but a number of important factors. For one, they didn’t believe Parliament should have the authority to tax the colonies if they didn’t have a representative there to act in their interests. Also, Britain had essentially formed a tea monopoly (by only allowing colonies to buy from one source) and colonists feared this could later extend to other goods.

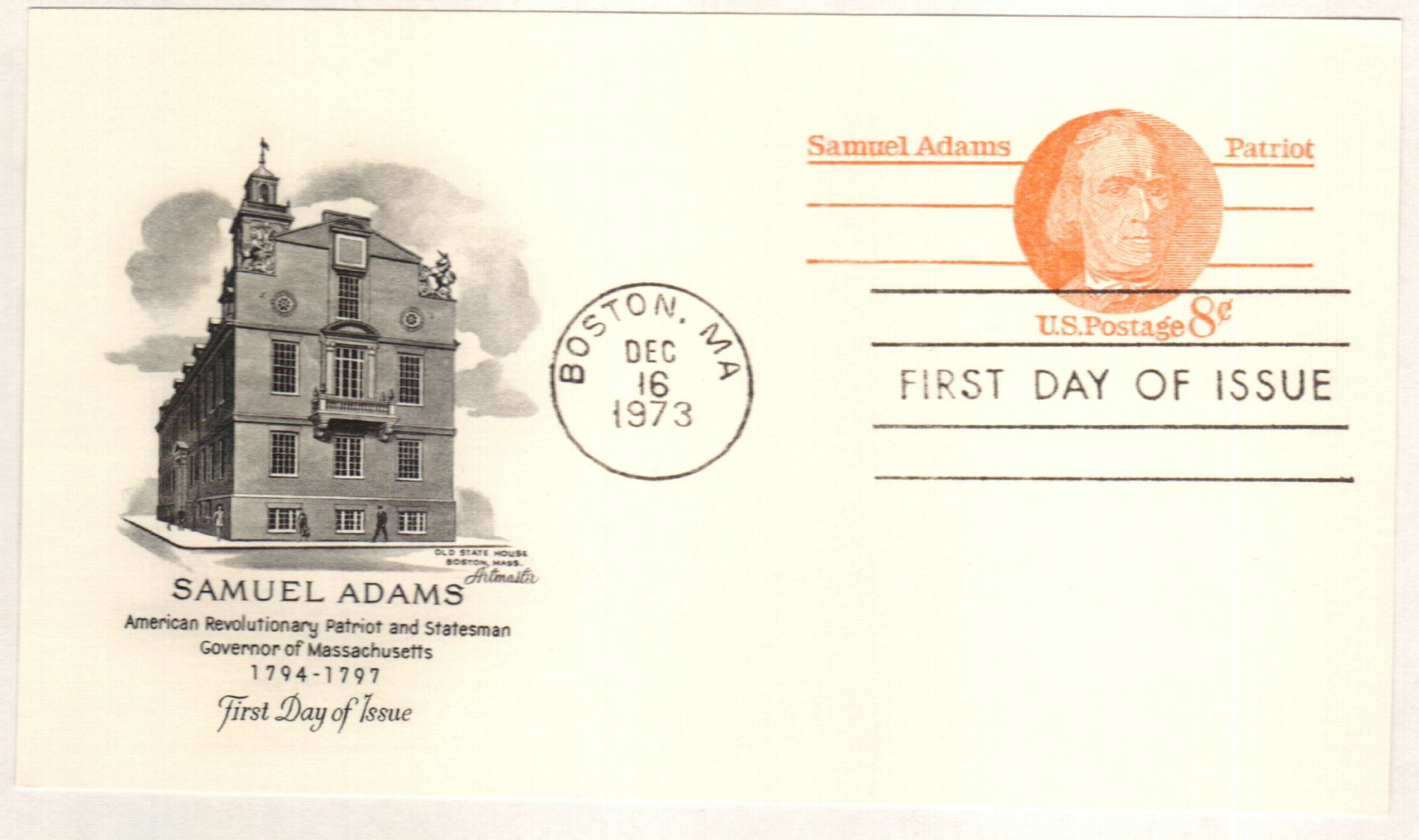

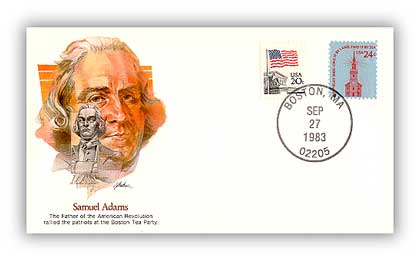

In the early fall of 1773, Britain sent seven ships carrying 600,000 pounds of tea to the colonies. Protesters met with the consignees (colonial merchants who would sell the incoming tea) and convinced many of them to resign and send the arriving tea back to England. In fact, they resigned everywhere except Massachusetts. The colonial governor there refused to back down and convinced his consignees not to resign. On November 29, when the tea ship arrived in Boston Harbor, Samuel Adams called for a meeting. Thousands turned out, and Adams presented a resolution, urging the ship’s captain to take the tea back to England. The governor refused to allow the ship to leave without paying the duty.

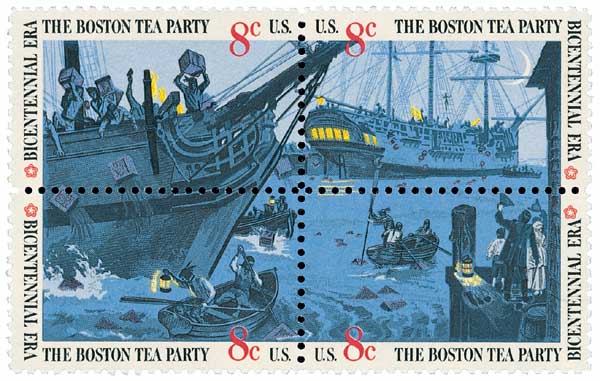

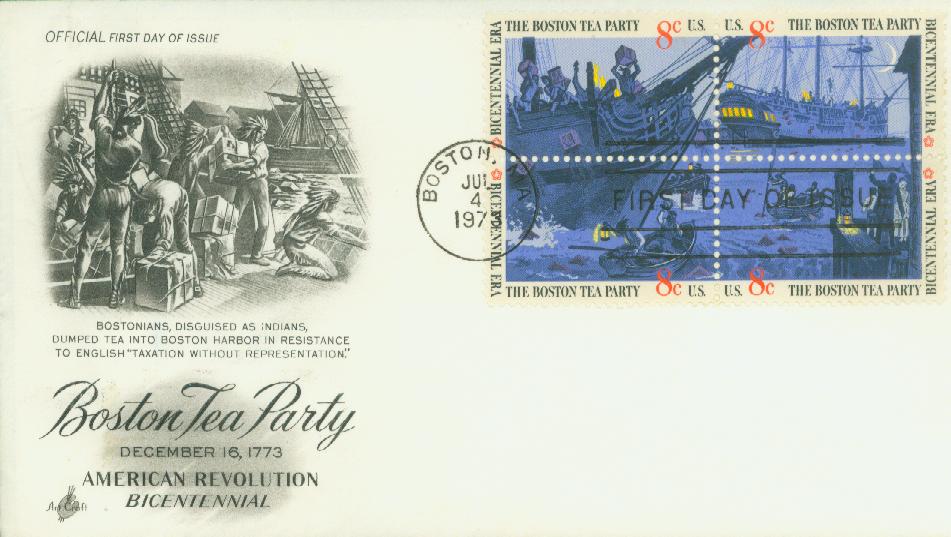

Unfazed by the governor’s resistance, Adams called another meeting on December 16. But upon hearing that the governor once again refused to let the ships leave, Adams declared that “this meeting can do nothing further to save the country.” Shortly after some 100 to 130 men left the meeting for the harbor. Some of them painted their faces and donned the clothes of Mohawk Warriors. After dark, they boarded the three British ships, and dumped all 342 chests of tea into the harbor. The tea was valued at 9,000 pounds sterling – a tremendous sum of money.

It’s been debated whether Adams helped plan the Boston Tea Party or not. Either way, once it was over, he widely publicized and defended it. Similar “tea parties” soon took place elsewhere in America, and the British government was outraged. Following the Boston Tea Party, the British Parliament decided on harsher means to make the colonies more cooperative. Parliament passed a series of laws they called the Coercive Acts – bluntly called the Intolerable Acts by American patriots. These laws greatly restricted the colonies, particularly Massachusetts, which lost its self-government and commerce.

Colonists felt the rules were a threat to their rights, and formed the First Continental Congress to discuss the situation. This led to greater unity among the colonies and increased support for independence, setting the stage for the Revolutionary War.

Set of 4

Colonists Revolt With Boston Tea Party

On December 16, 1773, a group of Massachusetts colonists known as the Sons of Liberty staged a dramatic protest against British taxes – the famed Boston Tea Party.

The French and Indian War left Britain in debt. So taxes were levied on the New World colonies, which enraged colonists as they had no say in government. The slogan, “No taxation without representation,” became popular in Massachusetts and protests were staged. In 1770, British soldiers fired on a group of angry patriots, killing five of them. The Boston Massacre, as it came to be known, sparked public sentiment against the British.

Britain continued to impose new tea taxes on the colonies. The colonists weren’t simply upset at the taxes themselves, but a number of important factors. For one, they didn’t believe Parliament should have the authority to tax the colonies if they didn’t have a representative there to act in their interests. Also, Britain had essentially formed a tea monopoly (by only allowing colonies to buy from one source) and colonists feared this could later extend to other goods.

In the early fall of 1773, Britain sent seven ships carrying 600,000 pounds of tea to the colonies. Protesters met with the consignees (colonial merchants who would sell the incoming tea) and convinced many of them to resign and send the arriving tea back to England. In fact, they resigned everywhere except Massachusetts. The colonial governor there refused to back down and convinced his consignees not to resign. On November 29, when the tea ship arrived in Boston Harbor, Samuel Adams called for a meeting. Thousands turned out, and Adams presented a resolution, urging the ship’s captain to take the tea back to England. The governor refused to allow the ship to leave without paying the duty.

Unfazed by the governor’s resistance, Adams called another meeting on December 16. But upon hearing that the governor once again refused to let the ships leave, Adams declared that “this meeting can do nothing further to save the country.” Shortly after some 100 to 130 men left the meeting for the harbor. Some of them painted their faces and donned the clothes of Mohawk Warriors. After dark, they boarded the three British ships, and dumped all 342 chests of tea into the harbor. The tea was valued at 9,000 pounds sterling – a tremendous sum of money.

It’s been debated whether Adams helped plan the Boston Tea Party or not. Either way, once it was over, he widely publicized and defended it. Similar “tea parties” soon took place elsewhere in America, and the British government was outraged. Following the Boston Tea Party, the British Parliament decided on harsher means to make the colonies more cooperative. Parliament passed a series of laws they called the Coercive Acts – bluntly called the Intolerable Acts by American patriots. These laws greatly restricted the colonies, particularly Massachusetts, which lost its self-government and commerce.

Colonists felt the rules were a threat to their rights, and formed the First Continental Congress to discuss the situation. This led to greater unity among the colonies and increased support for independence, setting the stage for the Revolutionary War.