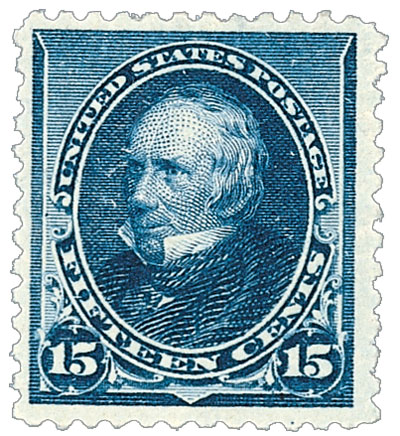

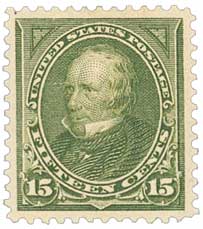

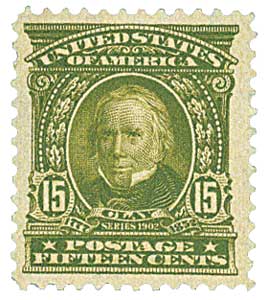

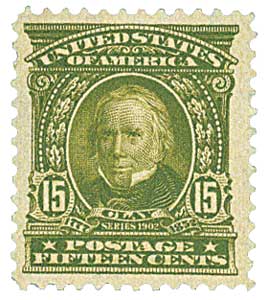

# 309 - 1903 15c Clay, olive green

Series of 1902-03 15¢ Clay

Quantity issued: 41,205,754 (estimate)

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Method: Flat plate

Watermark: Double line

Perforation: 12

Color: Olive green

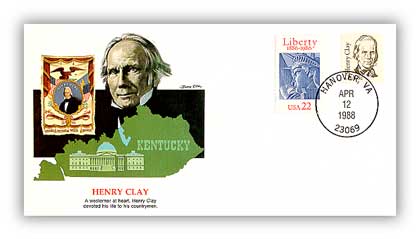

Death Of Henry Clay

Henry Clay was born on April 12, 1777, in Hanover County, Virginia. The seventh of nine children, Clay began working as a secretary at the Virginia Court of Chancery at a young age. From there he went on to work for the attorney general, where he developed an interest in and began studying the law. He was admitted to the bar in 1797.

That same year, Clay moved to Lexington, Kentucky, where he quickly became well known for his legal skills and courtroom speeches. Over the years many of his clients paid him with horses and plots of land. So by 1812, Clay had a 600-acre plantation known as Ashland.

In 1803 Clay was made a representative of Fayette County in the Kentucky General Assembly, even though he wasn’t old enough to be elected. In this role he supported moving the state capitol from Frankfort to Lexington. While he personally supported the gradual end of slavery in Kentucky (Clay had up to 60 slaves at his own plantation), he wasn’t able to promote the idea due to opposition from the slaveholding elite.

Clay’s popularity rose quickly in the coming years, so that when a Senate seat needed to be filled, he was selected and sworn in on December 29, 1806. Once again he was under the required age, but no one objected. He served the last two months of that term before returning to Kentucky in 1807. After that, Clay was elected Speaker of the United States House of Representatives.

In 1811, Clay was again elected to the U.S House of Representatives and this time made Speaker of the House on his first day (which has only ever happened one other time). Clay would be re-elected to that position five times in the next 14 years. While he was in that role, Clay vastly increased its political power, making it second only to the president. Clay initially opposed the creation of a National Bank because he personally owned several small banks in Lexington. However, he later changed his stance, offering his support for the Second Bank of the United States when he ran for the presidency.

In 1814, Clay helped negotiate and later signed the Treaty of Ghent, ending the War of 1812. Two years later he worked with John C. Calhoun to pass the Tariff Act of 1816. The act was part of Clay’s national economic plan he called The American System, which was designed to help America compete with British manufacturing through tariffs. These tariffs, as well as the sale of public lands, would then go toward internal improvements such as new roads and canals.

In 1820, tensions between north and south erupted when Missouri wanted to enter the Union as a slave state. Clay earned his nickname, “The Great Compromiser,” in developing the Missouri Compromise. This agreement admitted Maine as a free state and permitted slavery in the new state of Missouri, but prohibited it in most of the Louisiana Territory, a huge area west of the Mississippi River. This maintained the balance in the Senate of 11 slave and 11 free states.

Clay was still serving as Speaker of the House of Representatives when he campaigned for President in 1824. Four candidates split the field, with no one receiving a majority of Electoral votes. The top two candidates were presented to the House of Representatives to decide the outcome of the election. Clay’s political views were closer to those of John Quincy Adams than Andrew Jackson, and the Speaker used his influence to elect Adams. President John Quincy Adams appointed Henry Clay as his Secretary of State, a position he’d long desired. Jackson and his supporters called the move a “corrupt bargain.”

As Secretary of State, Clay made trade agreements with newly independent Latin American countries. He sought to have the U.S. involved in the Pan-American Congress of 1826, but Congress approved the measure too late. Adams was not reelected for a second term and Clay returned to his home in Kentucky until he was elected to the Senate in 1831. Two years later he worked on the Compromise Tariff of 1833, which lowered tariffs gradually. Between 1832 and 1848, Clay ran for president four more times, but never succeeded. After losing the Whig Party nomination in 1848, he hoped to retire to his Ashland estate. But the following year he was once again elected to the U.S. Senate.

By this time, America had received new land following the Mexican-American War. The issue of slavery spreading to new territories was again a concern. In response, Clay introduced the Compromise of 1850, which was as controversial as the slavery debate itself. Clay’s bill proposed the organization of Utah and New Mexico, leaving the decision of slavery to the people. The bill would also make California a free state and prohibit slave auctions in the District of Columbia. Additionally, the bill would introduce a new fugitive slave law. This ordered runaway slaves found anywhere in the United States be returned to their masters if a board of commissioners declared them fugitives. The bill would allow authorities to arrest African Americans and return them to slave territory, whether they were slaves or not. President Taylor refused to take a side on the issue, while Vice President Fillmore urged him to pass the bill.

Worn down by the constant fighting and weakened by tuberculosis, Clay left the capital and David Meriwether came in as his replacement. The compromise was ultimately passed after Taylor’s sudden death and Fillmore’s support.

Clay returned to Kentucky to live out his final years at Ashland. He succumbed to tuberculosis on June 29, 1852. His will freed all of his slaves.

In later years, President Abraham Lincoln said Clay was “my ideal of a great man.” And in 1957, a Senate committee called Clay one of the five greatest U.S. senators in American history.

Series of 1902-03 15¢ Clay

Quantity issued: 41,205,754 (estimate)

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Method: Flat plate

Watermark: Double line

Perforation: 12

Color: Olive green

Death Of Henry Clay

Henry Clay was born on April 12, 1777, in Hanover County, Virginia. The seventh of nine children, Clay began working as a secretary at the Virginia Court of Chancery at a young age. From there he went on to work for the attorney general, where he developed an interest in and began studying the law. He was admitted to the bar in 1797.

That same year, Clay moved to Lexington, Kentucky, where he quickly became well known for his legal skills and courtroom speeches. Over the years many of his clients paid him with horses and plots of land. So by 1812, Clay had a 600-acre plantation known as Ashland.

In 1803 Clay was made a representative of Fayette County in the Kentucky General Assembly, even though he wasn’t old enough to be elected. In this role he supported moving the state capitol from Frankfort to Lexington. While he personally supported the gradual end of slavery in Kentucky (Clay had up to 60 slaves at his own plantation), he wasn’t able to promote the idea due to opposition from the slaveholding elite.

Clay’s popularity rose quickly in the coming years, so that when a Senate seat needed to be filled, he was selected and sworn in on December 29, 1806. Once again he was under the required age, but no one objected. He served the last two months of that term before returning to Kentucky in 1807. After that, Clay was elected Speaker of the United States House of Representatives.

In 1811, Clay was again elected to the U.S House of Representatives and this time made Speaker of the House on his first day (which has only ever happened one other time). Clay would be re-elected to that position five times in the next 14 years. While he was in that role, Clay vastly increased its political power, making it second only to the president. Clay initially opposed the creation of a National Bank because he personally owned several small banks in Lexington. However, he later changed his stance, offering his support for the Second Bank of the United States when he ran for the presidency.

In 1814, Clay helped negotiate and later signed the Treaty of Ghent, ending the War of 1812. Two years later he worked with John C. Calhoun to pass the Tariff Act of 1816. The act was part of Clay’s national economic plan he called The American System, which was designed to help America compete with British manufacturing through tariffs. These tariffs, as well as the sale of public lands, would then go toward internal improvements such as new roads and canals.

In 1820, tensions between north and south erupted when Missouri wanted to enter the Union as a slave state. Clay earned his nickname, “The Great Compromiser,” in developing the Missouri Compromise. This agreement admitted Maine as a free state and permitted slavery in the new state of Missouri, but prohibited it in most of the Louisiana Territory, a huge area west of the Mississippi River. This maintained the balance in the Senate of 11 slave and 11 free states.

Clay was still serving as Speaker of the House of Representatives when he campaigned for President in 1824. Four candidates split the field, with no one receiving a majority of Electoral votes. The top two candidates were presented to the House of Representatives to decide the outcome of the election. Clay’s political views were closer to those of John Quincy Adams than Andrew Jackson, and the Speaker used his influence to elect Adams. President John Quincy Adams appointed Henry Clay as his Secretary of State, a position he’d long desired. Jackson and his supporters called the move a “corrupt bargain.”

As Secretary of State, Clay made trade agreements with newly independent Latin American countries. He sought to have the U.S. involved in the Pan-American Congress of 1826, but Congress approved the measure too late. Adams was not reelected for a second term and Clay returned to his home in Kentucky until he was elected to the Senate in 1831. Two years later he worked on the Compromise Tariff of 1833, which lowered tariffs gradually. Between 1832 and 1848, Clay ran for president four more times, but never succeeded. After losing the Whig Party nomination in 1848, he hoped to retire to his Ashland estate. But the following year he was once again elected to the U.S. Senate.

By this time, America had received new land following the Mexican-American War. The issue of slavery spreading to new territories was again a concern. In response, Clay introduced the Compromise of 1850, which was as controversial as the slavery debate itself. Clay’s bill proposed the organization of Utah and New Mexico, leaving the decision of slavery to the people. The bill would also make California a free state and prohibit slave auctions in the District of Columbia. Additionally, the bill would introduce a new fugitive slave law. This ordered runaway slaves found anywhere in the United States be returned to their masters if a board of commissioners declared them fugitives. The bill would allow authorities to arrest African Americans and return them to slave territory, whether they were slaves or not. President Taylor refused to take a side on the issue, while Vice President Fillmore urged him to pass the bill.

Worn down by the constant fighting and weakened by tuberculosis, Clay left the capital and David Meriwether came in as his replacement. The compromise was ultimately passed after Taylor’s sudden death and Fillmore’s support.

Clay returned to Kentucky to live out his final years at Ashland. He succumbed to tuberculosis on June 29, 1852. His will freed all of his slaves.

In later years, President Abraham Lincoln said Clay was “my ideal of a great man.” And in 1957, a Senate committee called Clay one of the five greatest U.S. senators in American history.