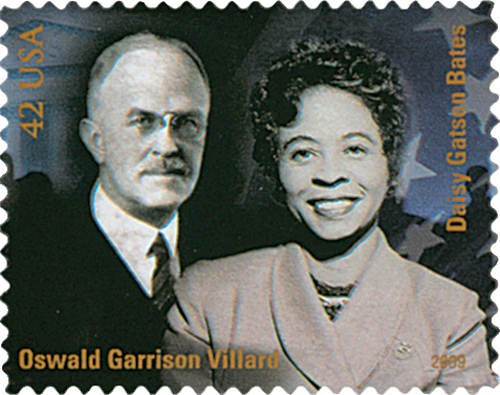

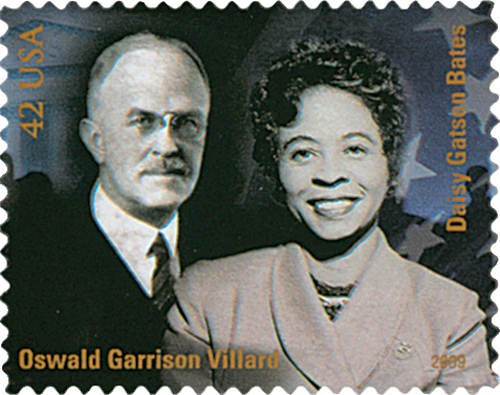

# 4384c - 2009 42c Civil Rights Pioneers: Oswald Garrison Villard and Daisy Bates

Civil Rights Pioneers

Oswald Garrison Villard and Daisy Bates

City: New York, NY

The grandson of abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, Oswald Garrison Villard (1872-1949) inherited the New York Evening Post and The Nation upon the death of his father. A life-long crusader, Villard wrote a series of articles that raised public awareness of social injustice.

Outraged by the brutality of the 1908 race riots, Villard used his newspapers to call for a national conference on the civil and political rights of African Americans. Scheduled to coincide with the centennial of Abraham Lincoln’s birth, the meeting led to the establishment of the NAACP in 1909.

Two years after Brown v. Board of Education declared school segregation illegal, Little Rock Central High School refused to allow African American students. Using her home as the group’s headquarters, Daisy Bates (1914-99) led nine African American students in their quest to integrate the school.

Rocks shattered the window of the Bates home during the month-long standoff, with a note that read, “Stone this time. Dynamite next.” Ignoring threats to her safety, Bates refused to back down. After several tense weeks, President Eisenhower ordered police and military escorts for the students. Facing an angry crowd of over 1,000 segregationists, the “Little Rock Nine” finally integrated Little Rock Central on September 25, 1957.

The Little Rock Nine Enter High School Under Federal Protection

After being initially denied entrance to their school, the Little Rock Nine were escorted in by federal troops on September 25, 1957.

On May 17, 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down a unanimous decision stating “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” It declared state laws establishing segregated schools to be unconstitutional and a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. A victory for civil rights advocates, the decision paved the way for integration. But the ruling was not acted on in all parts of the U.S., including Little Rock, Arkansas.

For the 1957-58 school year, Little Rock’s Central High School was to be integrated. About 75 black teenagers applied to go to the previously all-white Central High, but the school board accepted only nine. Governor Orval Faubus opposed the integration and ordered the Arkansas National Guard to surround the school and block the black students. He declared that if black students attempted to enter the school, “blood would run in the streets.” The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) stopped the Guard from continuing to block the students.

On September 23, the Little Rock Nine braved a mob outside the school to pass through the school doors. Inside, white students spit at them, tripped them, and yelled insults. With the mob outside growing more violent, the black students were led out a rear door. President Dwight Eisenhower responded by sending troops of the 101st Airborne Division to protect them. The 101st patrolled outside the school and accompanied each black student inside the school on September 25. A task force of Arkansas guardsmen then assumed the duty in November and continued to protect the students for the remainder of the year. Eight of the Little Rock Nine were able to endure and finish that historic school year.

Among those supporting the students through this ordeal was Daisy Bates. She offered up her home as their headquarters, putting herself in constant danger. Rocks were thrown at her windows with notes reading, “Stone this time. Dynamite next.” Ignoring threats to her safety, Bates refused to back down.

Civil Rights Pioneers

Oswald Garrison Villard and Daisy Bates

City: New York, NY

The grandson of abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, Oswald Garrison Villard (1872-1949) inherited the New York Evening Post and The Nation upon the death of his father. A life-long crusader, Villard wrote a series of articles that raised public awareness of social injustice.

Outraged by the brutality of the 1908 race riots, Villard used his newspapers to call for a national conference on the civil and political rights of African Americans. Scheduled to coincide with the centennial of Abraham Lincoln’s birth, the meeting led to the establishment of the NAACP in 1909.

Two years after Brown v. Board of Education declared school segregation illegal, Little Rock Central High School refused to allow African American students. Using her home as the group’s headquarters, Daisy Bates (1914-99) led nine African American students in their quest to integrate the school.

Rocks shattered the window of the Bates home during the month-long standoff, with a note that read, “Stone this time. Dynamite next.” Ignoring threats to her safety, Bates refused to back down. After several tense weeks, President Eisenhower ordered police and military escorts for the students. Facing an angry crowd of over 1,000 segregationists, the “Little Rock Nine” finally integrated Little Rock Central on September 25, 1957.

The Little Rock Nine Enter High School Under Federal Protection

After being initially denied entrance to their school, the Little Rock Nine were escorted in by federal troops on September 25, 1957.

On May 17, 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down a unanimous decision stating “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” It declared state laws establishing segregated schools to be unconstitutional and a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. A victory for civil rights advocates, the decision paved the way for integration. But the ruling was not acted on in all parts of the U.S., including Little Rock, Arkansas.

For the 1957-58 school year, Little Rock’s Central High School was to be integrated. About 75 black teenagers applied to go to the previously all-white Central High, but the school board accepted only nine. Governor Orval Faubus opposed the integration and ordered the Arkansas National Guard to surround the school and block the black students. He declared that if black students attempted to enter the school, “blood would run in the streets.” The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) stopped the Guard from continuing to block the students.

On September 23, the Little Rock Nine braved a mob outside the school to pass through the school doors. Inside, white students spit at them, tripped them, and yelled insults. With the mob outside growing more violent, the black students were led out a rear door. President Dwight Eisenhower responded by sending troops of the 101st Airborne Division to protect them. The 101st patrolled outside the school and accompanied each black student inside the school on September 25. A task force of Arkansas guardsmen then assumed the duty in November and continued to protect the students for the remainder of the year. Eight of the Little Rock Nine were able to endure and finish that historic school year.

Among those supporting the students through this ordeal was Daisy Bates. She offered up her home as their headquarters, putting herself in constant danger. Rocks were thrown at her windows with notes reading, “Stone this time. Dynamite next.” Ignoring threats to her safety, Bates refused to back down.