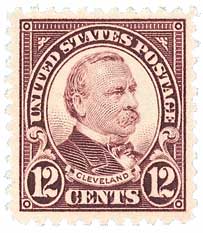

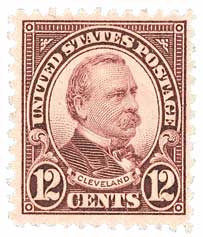

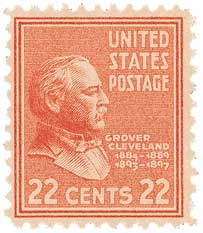

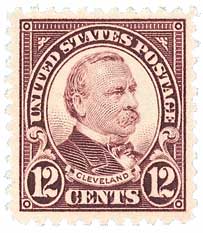

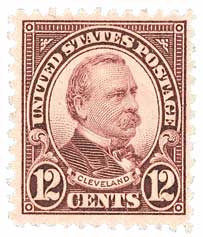

# 564 - 1923 12c Cleveland, perf 11

U.S. #564

Series of 1922-25

12¢ Cleveland

Issue Date: March 20, 1923

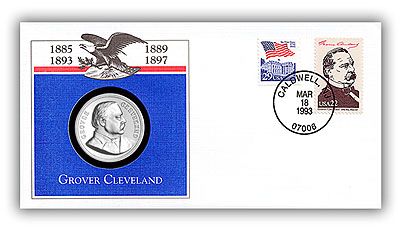

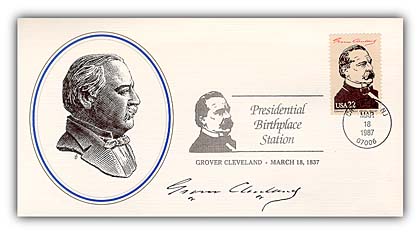

First City: Boston, MA, Caldwell, NJ and Washington, DC

Issue Quantity: 447,511,777

Wheels of Progress

In 1847, when the printing presses first began to move, they didn’t roll – they “stamped” in a process known as flat plate printing. The Regular Series of 1922 was the last to be printed by flat plate press, after which stamps were produced by rotary press printing.

By 1926, all denominations up to 10¢ – except the new ½¢ – were printed by rotary press. For a while, $1 to $5 issues were done on flat plate press due to smaller demand.

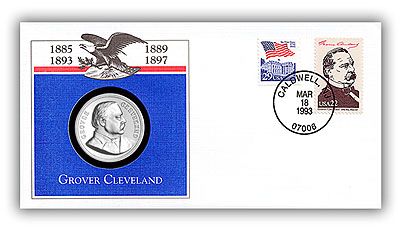

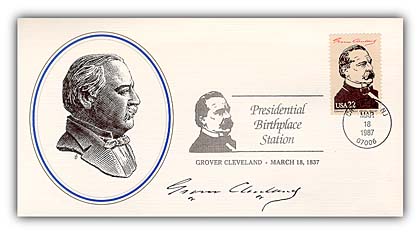

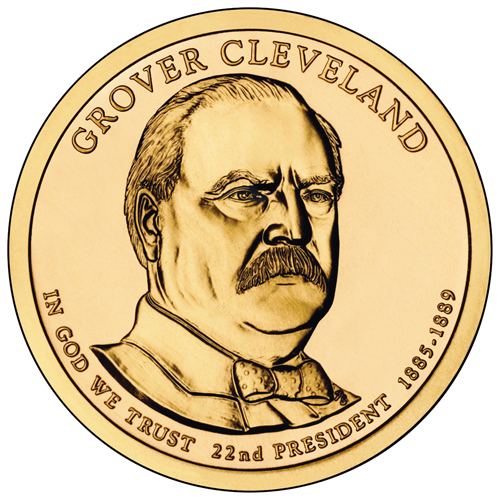

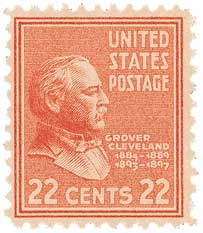

Death Of President Grover Cleveland

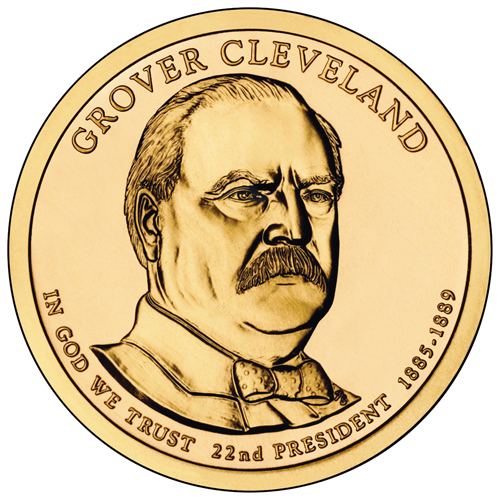

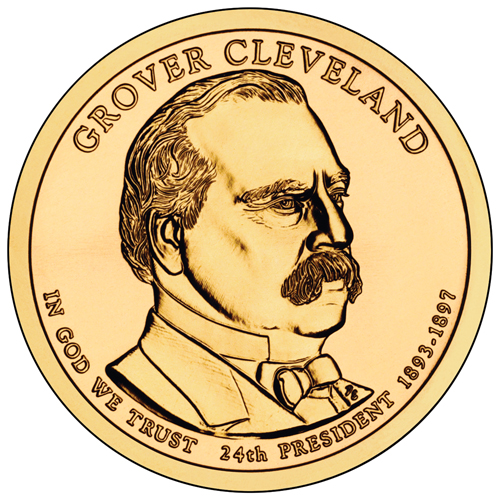

America’s 22nd and 24th president, Grover Cleveland, died on June 24, 1908, in Princeton, New Jersey.

Stephen Grover Cleveland was born in Caldwell, New Jersey, on March 18, 1837. He was a distant relative of General Moses Cleveland, the namesake of Cleveland, Ohio. The future president was named after the first pastor of his father’s church. However, he preferred to go by his middle name of Grover later in life.

The Cleveland family moved to Fayetteville, New York, in 1841, where Grover spent much of his childhood. After his father died, Grover left school to help support his family. Grover later set out west, stopping in Buffalo, New York, where he worked as a clerk in his uncle’s office and was introduced to the influential law partners of Rogers, Bowen, and Rogers. He then worked as a clerk in their office before being admitted to the bar in 1859.

Cleveland remained with the firm for three years before leaving in 1862 to start his own practice. The following year, he was made assistant district attorney of Erie County. Cleveland had a prosperous law career. He became well known for his intense concentration and hard work, often presenting his arguments from memory.

A major stepping-stone on Cleveland’s path to the presidency came in 1881. Up to that point, the Republican Buffalo government had grown increasingly corrupt.

So the Democrats sought out the most honest candidate they could find – Grover Cleveland. Cleveland won the election by more than 3,500 votes. He spent much of his term as mayor battling the interests of party machines. Cleveland frequently worked to protect public funds, building his reputation as an honest politician.

In 1882, the New York State Democratic Party selected Cleveland as their candidate for governor. He won the election by more than 192,000 votes – the largest margin of victory in the state up to that time. Within his first two months in office, Cleveland sent the legislature eight vetoes.

Two years later, Cleveland was a natural choice for the Democratic presidential candidate. He won the election of 1884 by one-quarter of a percent of the popular vote, and with an electoral vote of 219 to 182. When he delivered his inaugural address the following March, he did so without the use of notes, which no other President had done before.

Cleveland worked to reform other parts of the government, such as in 1887, when he signed the legislation establishing the Interstate Commerce Commission. He also worked with the secretary of the Navy to modernize and cancel construction contracts that resulted in faulty ships. Squaring off against the Republican Senate, Cleveland used his veto power a great deal more than any other president up to that time. He vetoed hundreds of private pension bills for Civil War veterans, believing Congress should not override the Pension Bureau’s decision.

As a non-interventionist opposing expansion and imperialism, Cleveland had little concern for foreign policy. He was against the previous administration’s Nicaragua Canal Treaty, and discouraged the Senate from talks about the Berlin Conference Treaty, which would have opened doors for the US in the Congo.

Concerning civil rights, Cleveland saw Reconstruction as a failed experiment and hesitated to use federal power to enforce the 15th Amendment guaranteeing African-Americans the right to vote. Cleveland took a more positive stance concerning Native-Americans, saying in his inaugural address that, “[t]his guardianship involves, on our part, efforts for the improvement of their condition and enforcement of their rights.” He supported the Dawes Act, which would distribute Indian lands to individuals, rather than being held in trusts by the Federal government. Cleveland saw the act as a means to lift the Native-Americans out of poverty and join white society. However, it actually weakened the tribal governments and many individuals sold their lands.

As the election of 1888 approached, the tariff issue took center stage. The Republicans, with Benjamin Harrison as their candidate, campaigned to keep tariffs high, gaining the support of industrialists and factory workers. Cleveland stuck to his position that high tariffs were unfair to consumers. Although Cleveland narrowly won the popular vote, Harrison took the Electoral College. This was the third time in US history that the winner of the popular vote did not win the election.

While Cleveland looked forward to the peace of private life, his young wife, Frances, instructed the staff to take good care of the furniture and decorations, “for I want to find everything just as it is now, when we come back again.” When asked when they would return, she said, “four years from today.” Little did President Cleveland know just how right she would be.

While Cleveland happily enjoyed private life in New York City, President Harrison’s administration passed the McKinley Tariff and Sherman Silver Purchase Act. Cleveland saw both of these policies as dangerous for the nation’s economy. While he initially decided not to speak out about his outrage, he later felt it was his duty to address these concerns. Cleveland submitted an open “silver letter” to a meeting of reformers in New York. This letter made Cleveland a national name once again, just as the 1892 election approached. He went on to win that election, returning to the White House as his wife had foretold.

Shortly after Cleveland entered office, the Panic of 1893 struck the stock market and the country was in a state of acute economic depression. After 15 weeks of debate, the Senate repealed the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, eventually returning the Treasury’s gold reserves to safe levels.

Next, Cleveland then turned his attention to reversing the McKinley tariff. Though he considered the new Wilson-Gorman Tariff Act to be “a disgraceful product of the control of the Senate by trusts and business interests,” he still considered it an improvement over the McKinley Tariff and allowed it to become law.

Anti-Cleveland agrarian and silverite Democrats took control of the party in 1896, rejected his administration and the gold standard and nominated William Jennings Bryan. Cleveland supported the Gold Democrats’ third-party ticket but decided not to accept their nomination for a third term. In the end, Republican William McKinley won the election.

After leaving the White House in 1897, Cleveland retired to his estate at Westfield Mansion in Princeton, New Jersey. He served briefly as a trustee of Princeton University and consulted with President Theodore Roosevelt during his time in office. After several years of poor health, Cleveland became seriously ill in 1907 and suffered a heart attack the following year, dying on June 24. His final words were, “I have tried so hard to do right.”

U.S. #564

Series of 1922-25

12¢ Cleveland

Issue Date: March 20, 1923

First City: Boston, MA, Caldwell, NJ and Washington, DC

Issue Quantity: 447,511,777

Wheels of Progress

In 1847, when the printing presses first began to move, they didn’t roll – they “stamped” in a process known as flat plate printing. The Regular Series of 1922 was the last to be printed by flat plate press, after which stamps were produced by rotary press printing.

By 1926, all denominations up to 10¢ – except the new ½¢ – were printed by rotary press. For a while, $1 to $5 issues were done on flat plate press due to smaller demand.

Death Of President Grover Cleveland

America’s 22nd and 24th president, Grover Cleveland, died on June 24, 1908, in Princeton, New Jersey.

Stephen Grover Cleveland was born in Caldwell, New Jersey, on March 18, 1837. He was a distant relative of General Moses Cleveland, the namesake of Cleveland, Ohio. The future president was named after the first pastor of his father’s church. However, he preferred to go by his middle name of Grover later in life.

The Cleveland family moved to Fayetteville, New York, in 1841, where Grover spent much of his childhood. After his father died, Grover left school to help support his family. Grover later set out west, stopping in Buffalo, New York, where he worked as a clerk in his uncle’s office and was introduced to the influential law partners of Rogers, Bowen, and Rogers. He then worked as a clerk in their office before being admitted to the bar in 1859.

Cleveland remained with the firm for three years before leaving in 1862 to start his own practice. The following year, he was made assistant district attorney of Erie County. Cleveland had a prosperous law career. He became well known for his intense concentration and hard work, often presenting his arguments from memory.

A major stepping-stone on Cleveland’s path to the presidency came in 1881. Up to that point, the Republican Buffalo government had grown increasingly corrupt.

So the Democrats sought out the most honest candidate they could find – Grover Cleveland. Cleveland won the election by more than 3,500 votes. He spent much of his term as mayor battling the interests of party machines. Cleveland frequently worked to protect public funds, building his reputation as an honest politician.

In 1882, the New York State Democratic Party selected Cleveland as their candidate for governor. He won the election by more than 192,000 votes – the largest margin of victory in the state up to that time. Within his first two months in office, Cleveland sent the legislature eight vetoes.

Two years later, Cleveland was a natural choice for the Democratic presidential candidate. He won the election of 1884 by one-quarter of a percent of the popular vote, and with an electoral vote of 219 to 182. When he delivered his inaugural address the following March, he did so without the use of notes, which no other President had done before.

Cleveland worked to reform other parts of the government, such as in 1887, when he signed the legislation establishing the Interstate Commerce Commission. He also worked with the secretary of the Navy to modernize and cancel construction contracts that resulted in faulty ships. Squaring off against the Republican Senate, Cleveland used his veto power a great deal more than any other president up to that time. He vetoed hundreds of private pension bills for Civil War veterans, believing Congress should not override the Pension Bureau’s decision.

As a non-interventionist opposing expansion and imperialism, Cleveland had little concern for foreign policy. He was against the previous administration’s Nicaragua Canal Treaty, and discouraged the Senate from talks about the Berlin Conference Treaty, which would have opened doors for the US in the Congo.

Concerning civil rights, Cleveland saw Reconstruction as a failed experiment and hesitated to use federal power to enforce the 15th Amendment guaranteeing African-Americans the right to vote. Cleveland took a more positive stance concerning Native-Americans, saying in his inaugural address that, “[t]his guardianship involves, on our part, efforts for the improvement of their condition and enforcement of their rights.” He supported the Dawes Act, which would distribute Indian lands to individuals, rather than being held in trusts by the Federal government. Cleveland saw the act as a means to lift the Native-Americans out of poverty and join white society. However, it actually weakened the tribal governments and many individuals sold their lands.

As the election of 1888 approached, the tariff issue took center stage. The Republicans, with Benjamin Harrison as their candidate, campaigned to keep tariffs high, gaining the support of industrialists and factory workers. Cleveland stuck to his position that high tariffs were unfair to consumers. Although Cleveland narrowly won the popular vote, Harrison took the Electoral College. This was the third time in US history that the winner of the popular vote did not win the election.

While Cleveland looked forward to the peace of private life, his young wife, Frances, instructed the staff to take good care of the furniture and decorations, “for I want to find everything just as it is now, when we come back again.” When asked when they would return, she said, “four years from today.” Little did President Cleveland know just how right she would be.

While Cleveland happily enjoyed private life in New York City, President Harrison’s administration passed the McKinley Tariff and Sherman Silver Purchase Act. Cleveland saw both of these policies as dangerous for the nation’s economy. While he initially decided not to speak out about his outrage, he later felt it was his duty to address these concerns. Cleveland submitted an open “silver letter” to a meeting of reformers in New York. This letter made Cleveland a national name once again, just as the 1892 election approached. He went on to win that election, returning to the White House as his wife had foretold.

Shortly after Cleveland entered office, the Panic of 1893 struck the stock market and the country was in a state of acute economic depression. After 15 weeks of debate, the Senate repealed the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, eventually returning the Treasury’s gold reserves to safe levels.

Next, Cleveland then turned his attention to reversing the McKinley tariff. Though he considered the new Wilson-Gorman Tariff Act to be “a disgraceful product of the control of the Senate by trusts and business interests,” he still considered it an improvement over the McKinley Tariff and allowed it to become law.

Anti-Cleveland agrarian and silverite Democrats took control of the party in 1896, rejected his administration and the gold standard and nominated William Jennings Bryan. Cleveland supported the Gold Democrats’ third-party ticket but decided not to accept their nomination for a third term. In the end, Republican William McKinley won the election.

After leaving the White House in 1897, Cleveland retired to his estate at Westfield Mansion in Princeton, New Jersey. He served briefly as a trustee of Princeton University and consulted with President Theodore Roosevelt during his time in office. After several years of poor health, Cleveland became seriously ill in 1907 and suffered a heart attack the following year, dying on June 24. His final words were, “I have tried so hard to do right.”