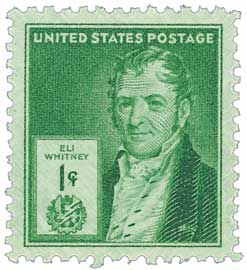

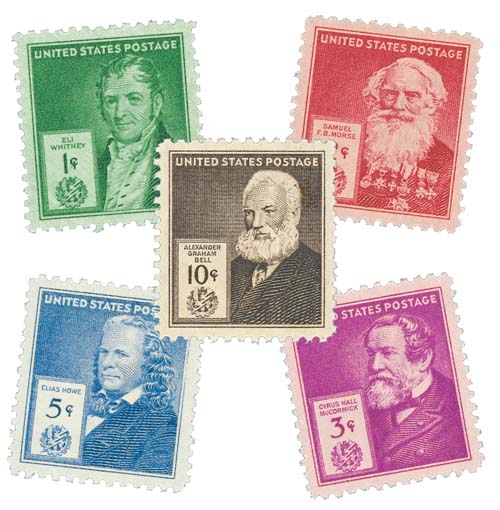

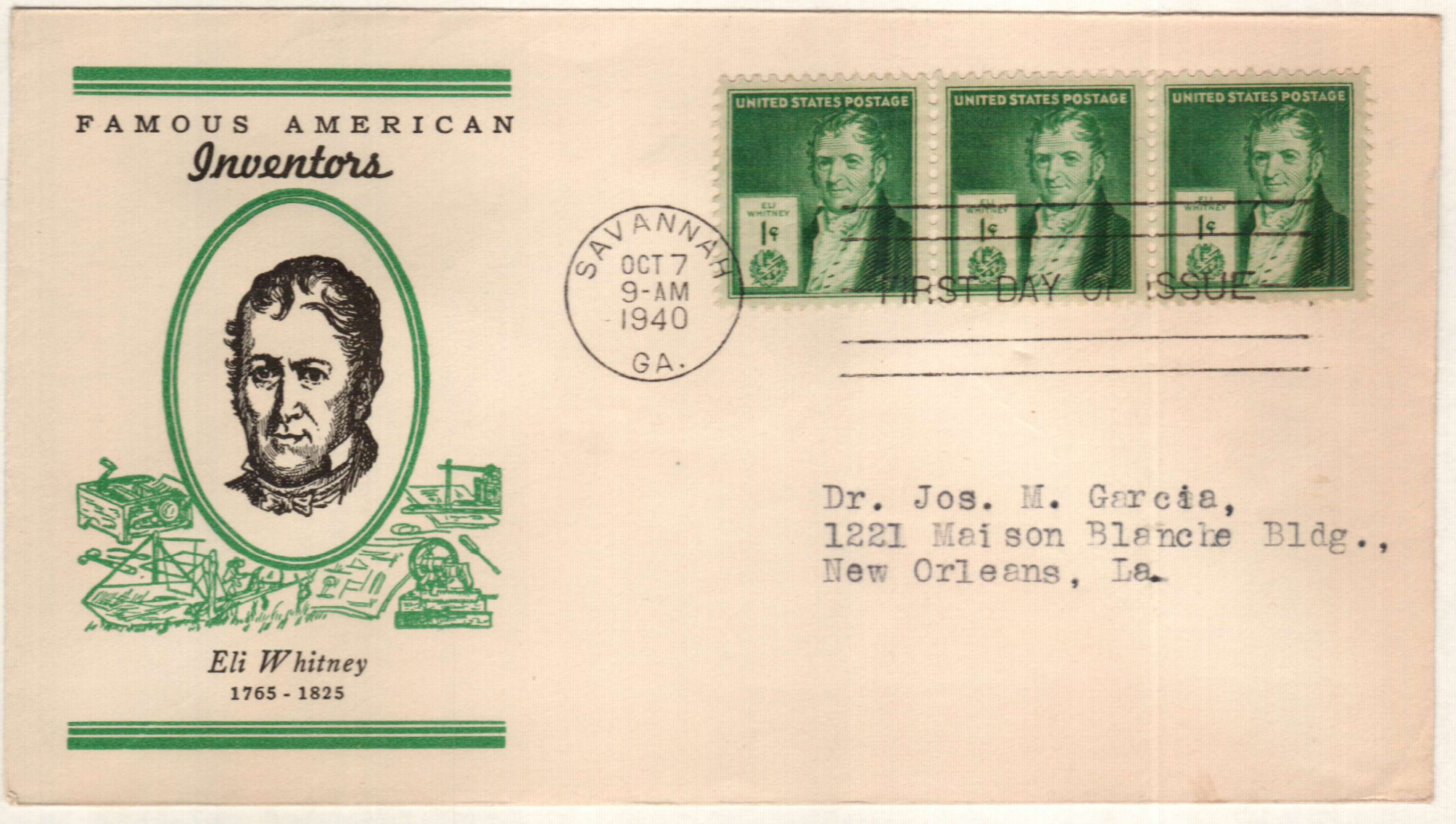

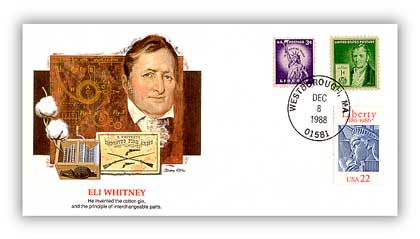

# 889 - 1940 Famous Americans: 1c Eli Whitney

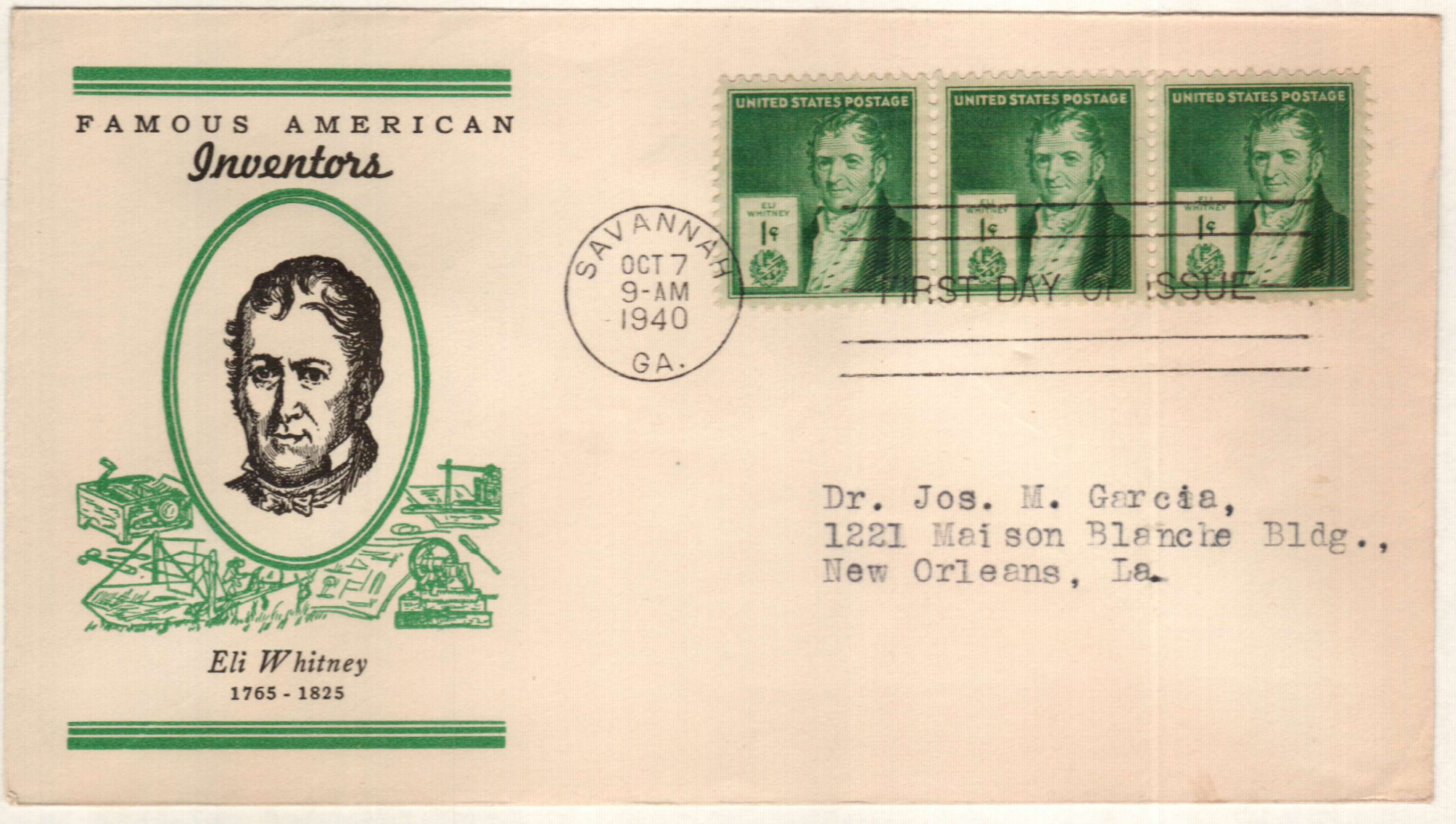

1940 1¢ Eli Whitney

Famous Americans Series – Inventors

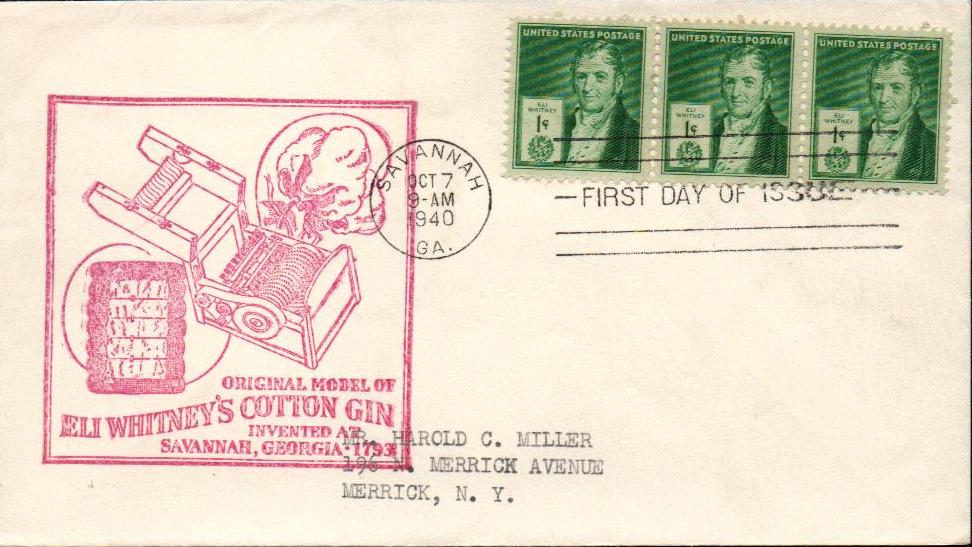

First City: Savannah, Georgia

Quantity Issued: 47,599,580

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Perforation: 10 ½ x 11

Color: Bright blue green

Birth Of Eli Whitney

Whitney was the son of a farmer and was a talented mechanic and inventor from an early age. As a child, he built a nail forge and a violin, among other things. After graduating from Yale College in 1792, he hoped to study to become a lawyer, but needed money. Instead, he took a job as a private tutor on the Georgia plantation of Catherine Greene (widow of Revolutionary General Nathanael Greene).

Living on the farm, Whitney quickly learned of the struggle of Southern planters. Many were growing short-staple cotton, a variety that was time-consuming to clean by hand. At that time, the average cotton picker could de-seed about a pound of cotton per day. Greene and her plantation manager Phineas Miller encouraged Whitney to devise a machine to improve the process. He believed that creating such an invention could be quite lucrative, so he set his plans to become a lawyer aside and spent several months designing and building his cotton gin (“gin” being taken from “engine”).

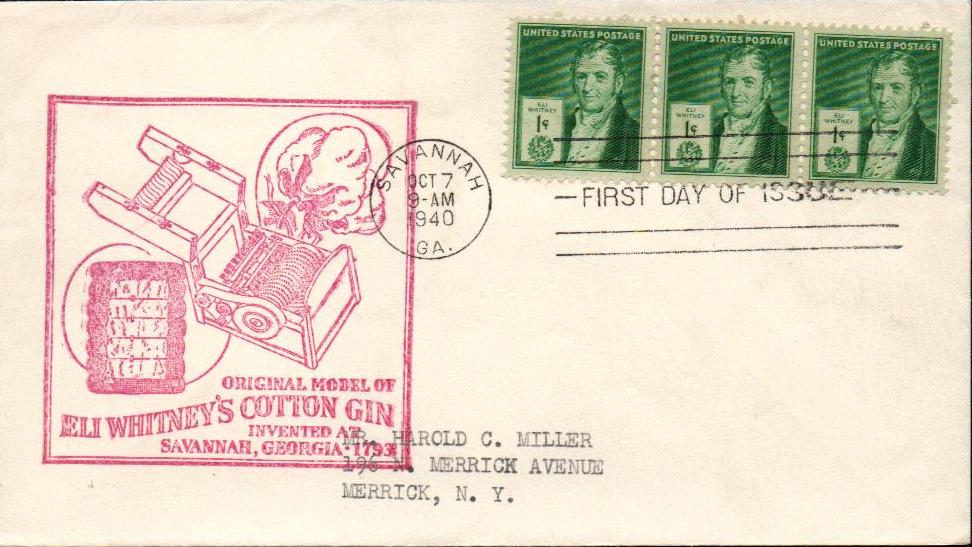

Reportedly, Whitney took his inspiration from watching a cat try to pull a chicken through a picket fence. When the cat succeeded in getting only feathers, Whitney was inspired to build his cotton gin – a wooden drum with hooks that pull cotton fibers through a mesh. Seeds, unable to fit through the fine mesh, fall outside. Whitney’s new machine allowed one person to remove seeds from up to 55 pounds of cotton in a single day.

Whitney applied for a patent on his new invention in October 1793. But it wasn’t until March 14, 1794, that his patent was officially approved. He and Miller, now his business partner, considered their options and decided to give the cotton gins to local farmers and take 40% of their profits in return. The farmers didn’t like this idea, seeing it as an unfair tax, and made their own versions of Whitney’s invention. Whitney and Miller filed several suits against these farmers, but were unable to win any of them until the patent law was changed in 1800.

Eventually Whitney and Miller decided to license the patent at a reasonable price – $50,000 to South Carolina alone. One unforeseen aspect of Whitney’s invention was that it fueled the growth of slavery in America. Though it reduced the amount of labor needed to remove seeds, it didn’t reduce the people needed to grow and pick the cotton. In fact, it made cotton so profitable for plantation owners that it increased their need for land – and slave labor. Some even claim that it was the cotton gin that eventually led to the Civil War, as it rejuvenated the slave industry.

In 1798, as the US faced the threat of war with France, the government contracted Whitney to manufacture 10,000 muskets in two years. Although he wasn’t the first to utilize any one of the methods, Whitney combined power machinery, interchangeable parts, and the division of labor in a way that had not been seen in America. Whitney’s winning bid took into account fixed costs, a practice that had not been used previously, thus changing the concept of cost accounting for industrial manufacturers. Though it eventually took him 10 years to fulfill his contract, Whitney is often credited as an early pioneer of American mass-production.

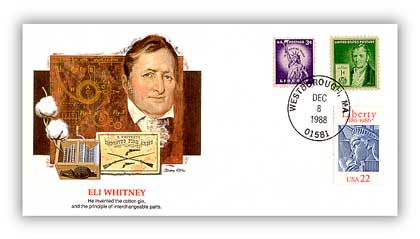

1940 1¢ Eli Whitney

Famous Americans Series – Inventors

First City: Savannah, Georgia

Quantity Issued: 47,599,580

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Perforation: 10 ½ x 11

Color: Bright blue green

Birth Of Eli Whitney

Whitney was the son of a farmer and was a talented mechanic and inventor from an early age. As a child, he built a nail forge and a violin, among other things. After graduating from Yale College in 1792, he hoped to study to become a lawyer, but needed money. Instead, he took a job as a private tutor on the Georgia plantation of Catherine Greene (widow of Revolutionary General Nathanael Greene).

Living on the farm, Whitney quickly learned of the struggle of Southern planters. Many were growing short-staple cotton, a variety that was time-consuming to clean by hand. At that time, the average cotton picker could de-seed about a pound of cotton per day. Greene and her plantation manager Phineas Miller encouraged Whitney to devise a machine to improve the process. He believed that creating such an invention could be quite lucrative, so he set his plans to become a lawyer aside and spent several months designing and building his cotton gin (“gin” being taken from “engine”).

Reportedly, Whitney took his inspiration from watching a cat try to pull a chicken through a picket fence. When the cat succeeded in getting only feathers, Whitney was inspired to build his cotton gin – a wooden drum with hooks that pull cotton fibers through a mesh. Seeds, unable to fit through the fine mesh, fall outside. Whitney’s new machine allowed one person to remove seeds from up to 55 pounds of cotton in a single day.

Whitney applied for a patent on his new invention in October 1793. But it wasn’t until March 14, 1794, that his patent was officially approved. He and Miller, now his business partner, considered their options and decided to give the cotton gins to local farmers and take 40% of their profits in return. The farmers didn’t like this idea, seeing it as an unfair tax, and made their own versions of Whitney’s invention. Whitney and Miller filed several suits against these farmers, but were unable to win any of them until the patent law was changed in 1800.

Eventually Whitney and Miller decided to license the patent at a reasonable price – $50,000 to South Carolina alone. One unforeseen aspect of Whitney’s invention was that it fueled the growth of slavery in America. Though it reduced the amount of labor needed to remove seeds, it didn’t reduce the people needed to grow and pick the cotton. In fact, it made cotton so profitable for plantation owners that it increased their need for land – and slave labor. Some even claim that it was the cotton gin that eventually led to the Civil War, as it rejuvenated the slave industry.

In 1798, as the US faced the threat of war with France, the government contracted Whitney to manufacture 10,000 muskets in two years. Although he wasn’t the first to utilize any one of the methods, Whitney combined power machinery, interchangeable parts, and the division of labor in a way that had not been seen in America. Whitney’s winning bid took into account fixed costs, a practice that had not been used previously, thus changing the concept of cost accounting for industrial manufacturers. Though it eventually took him 10 years to fulfill his contract, Whitney is often credited as an early pioneer of American mass-production.