# 941 - 1946 3c Tennessee Statehood

3¢ Tennessee Statehood 150th Anniversary

City: Nashville, TN

Quantity: 132,274,500

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Perforations: 11 x 10 1/2

Color: Dark violet

American Soldier, Frontiersman, and Politician

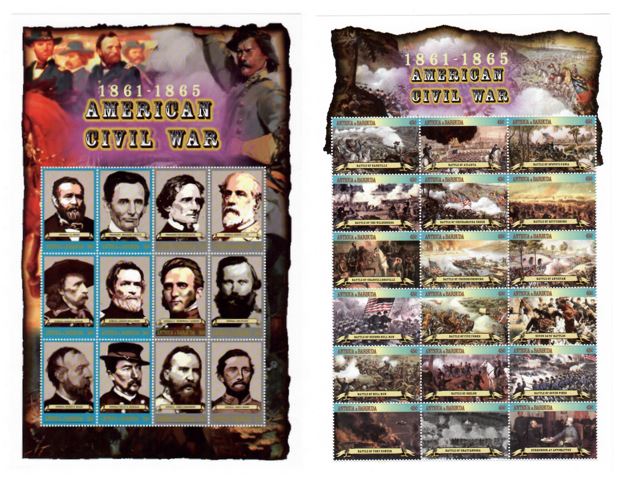

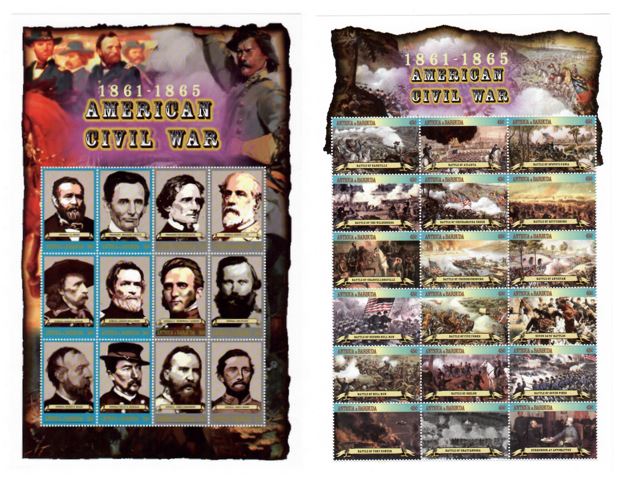

Battle Of Nashville

Confederate General John Bell Hood was defeated at Franklin, and his Army of Tennessee suffered great losses. In spite of being greatly outnumbered, he pressed on to the well-fortified stronghold of Nashville. On December 2, 1864, the Rebels approached the city from the south. Hood knew his forces were not strong enough to attack the Union, so the Southern army put up four miles of defenses and waited for the enemy to attack.

Major General John Schofield and his victorious Army of Ohio had arrived from Franklin the day before Hood’s men. They joined the Union forces that were already reinforcing the lines of defense around Nashville. The works stretched for seven miles in a semicircle, protecting the city on the south and west. The Cumberland River formed a natural defense around the rest. The troops inside numbered about 55,000 men. Major General George Thomas was in command.

Thomas began preparing for an assault on Hood. His cavalry needed fresh horses and better arms. The commander knew they would be facing Lieutenant General Nathan Bedford Forrest, one of the best cavalry leaders on either side of the war.

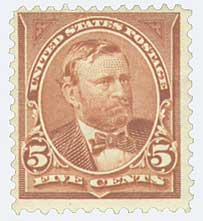

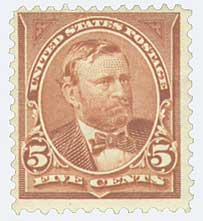

Leaders in Washington were getting impatient with the delay. They were concerned Hood would move away from Nashville and invade Kentucky or Ohio. Commander Ulysses S. Grant ordered a replacement to go to Nashville if Thomas did not begin his attack by December 13. In fact, Grant was on his way to take over himself when he heard Thomas had finally made his move.

In the early hours of December 15, Thomas sent two brigades toward the right of the Confederate line in the hopes of drawing Southern troops away from the main attack. These men had the least experience of any of the Union soldiers in Nashville and included three regiments of US Colored Troops, who had previously guarded the railroads. After overtaking the skirmish line, they faced heavy fire and retreated. The brigades reformed and held the Confederates for the rest of the day. Though they were successful in engaging forces on the right, Hood did not send additional support as Thomas predicted.

3¢ Tennessee Statehood 150th Anniversary

City: Nashville, TN

Quantity: 132,274,500

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Perforations: 11 x 10 1/2

Color: Dark violet

American Soldier, Frontiersman, and Politician

Battle Of Nashville

Confederate General John Bell Hood was defeated at Franklin, and his Army of Tennessee suffered great losses. In spite of being greatly outnumbered, he pressed on to the well-fortified stronghold of Nashville. On December 2, 1864, the Rebels approached the city from the south. Hood knew his forces were not strong enough to attack the Union, so the Southern army put up four miles of defenses and waited for the enemy to attack.

Major General John Schofield and his victorious Army of Ohio had arrived from Franklin the day before Hood’s men. They joined the Union forces that were already reinforcing the lines of defense around Nashville. The works stretched for seven miles in a semicircle, protecting the city on the south and west. The Cumberland River formed a natural defense around the rest. The troops inside numbered about 55,000 men. Major General George Thomas was in command.

Thomas began preparing for an assault on Hood. His cavalry needed fresh horses and better arms. The commander knew they would be facing Lieutenant General Nathan Bedford Forrest, one of the best cavalry leaders on either side of the war.

Leaders in Washington were getting impatient with the delay. They were concerned Hood would move away from Nashville and invade Kentucky or Ohio. Commander Ulysses S. Grant ordered a replacement to go to Nashville if Thomas did not begin his attack by December 13. In fact, Grant was on his way to take over himself when he heard Thomas had finally made his move.

In the early hours of December 15, Thomas sent two brigades toward the right of the Confederate line in the hopes of drawing Southern troops away from the main attack. These men had the least experience of any of the Union soldiers in Nashville and included three regiments of US Colored Troops, who had previously guarded the railroads. After overtaking the skirmish line, they faced heavy fire and retreated. The brigades reformed and held the Confederates for the rest of the day. Though they were successful in engaging forces on the right, Hood did not send additional support as Thomas predicted.