# K6 - 1919 12c on 6c Red Orange, Shanghai Overprint

The USPOD Philatelic Agency

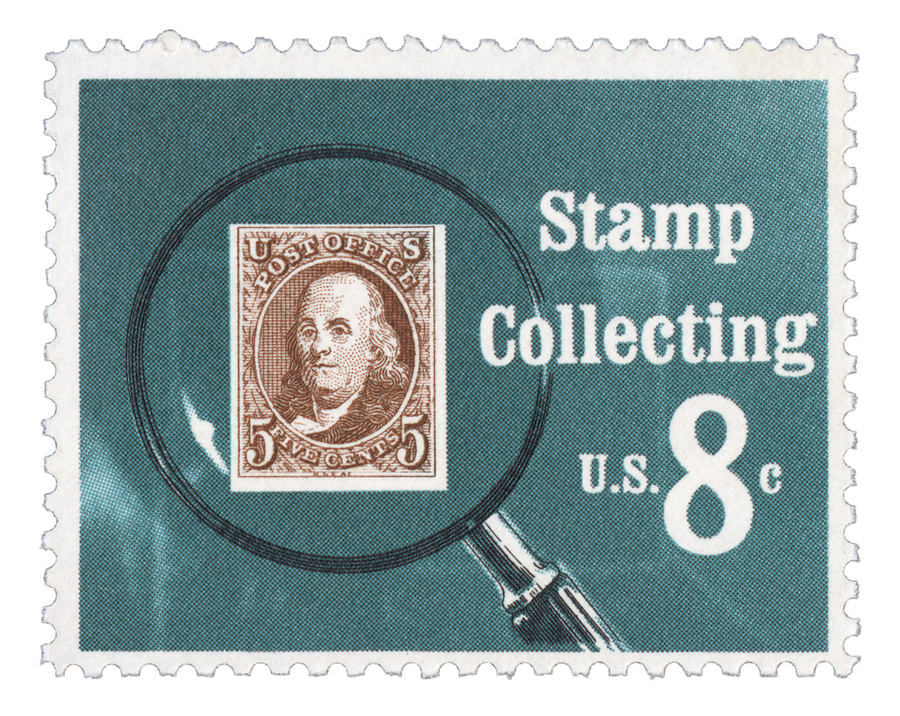

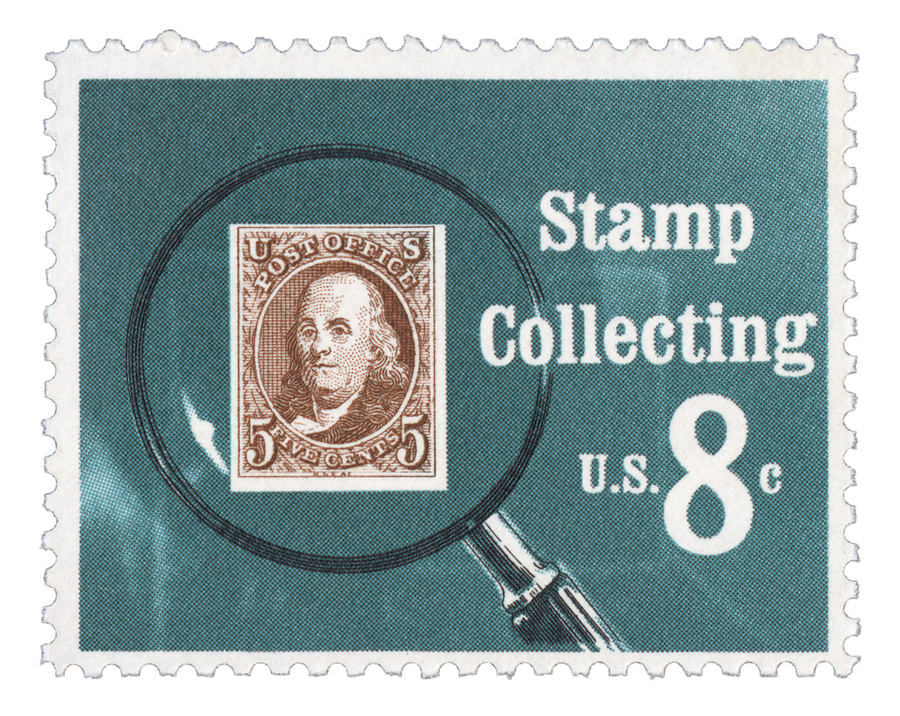

On December 1, 1921, the US Post Office Department opened its Philatelic Agency in Washington, DC, to the benefit of stamp collectors.

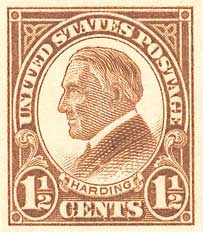

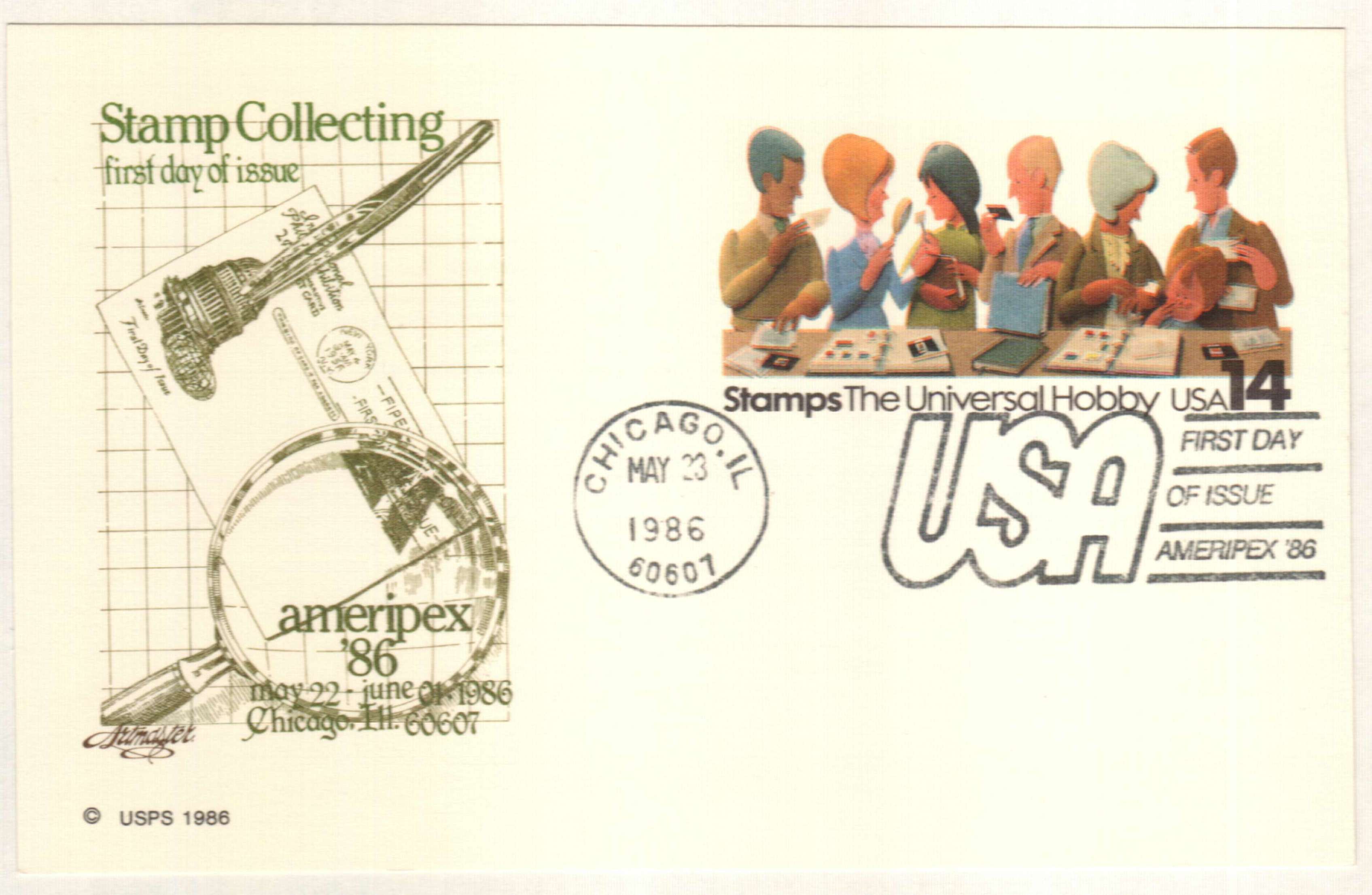

By the 1920s, stamp collecting had grown to be very popular both in the US and around the world. In spite of that popularity, the number of post offices in the country had dropped from over 76,000 in 1900 to about 52,000 in 1920. Collectors and dealers began writing directly to the Post Office Department to request harder to find stamps.

In 1917 a congressman who was also a collector recommended the creation of the Philatelic Agency. Soon others agreed, as creating this new office would allow the Post Office to expand its commemorative stamp program and keep track of the sales. They believed such an agency could help to consistently fund the Post Office Department and encourage stamp collecting. The Philatelic Agency was officially established on December 1, 1921.

The Postmaster General stated that the agency gave formal recognition to “the growing importance of stamp collecting” and that it would help both collectors and dealers. Mekeel’s Weekly, which had also requested such a move, saw this act as “humanizing the department.” To collectors, it indicated that the Postal Department took their efforts seriously and realized their growing importance.

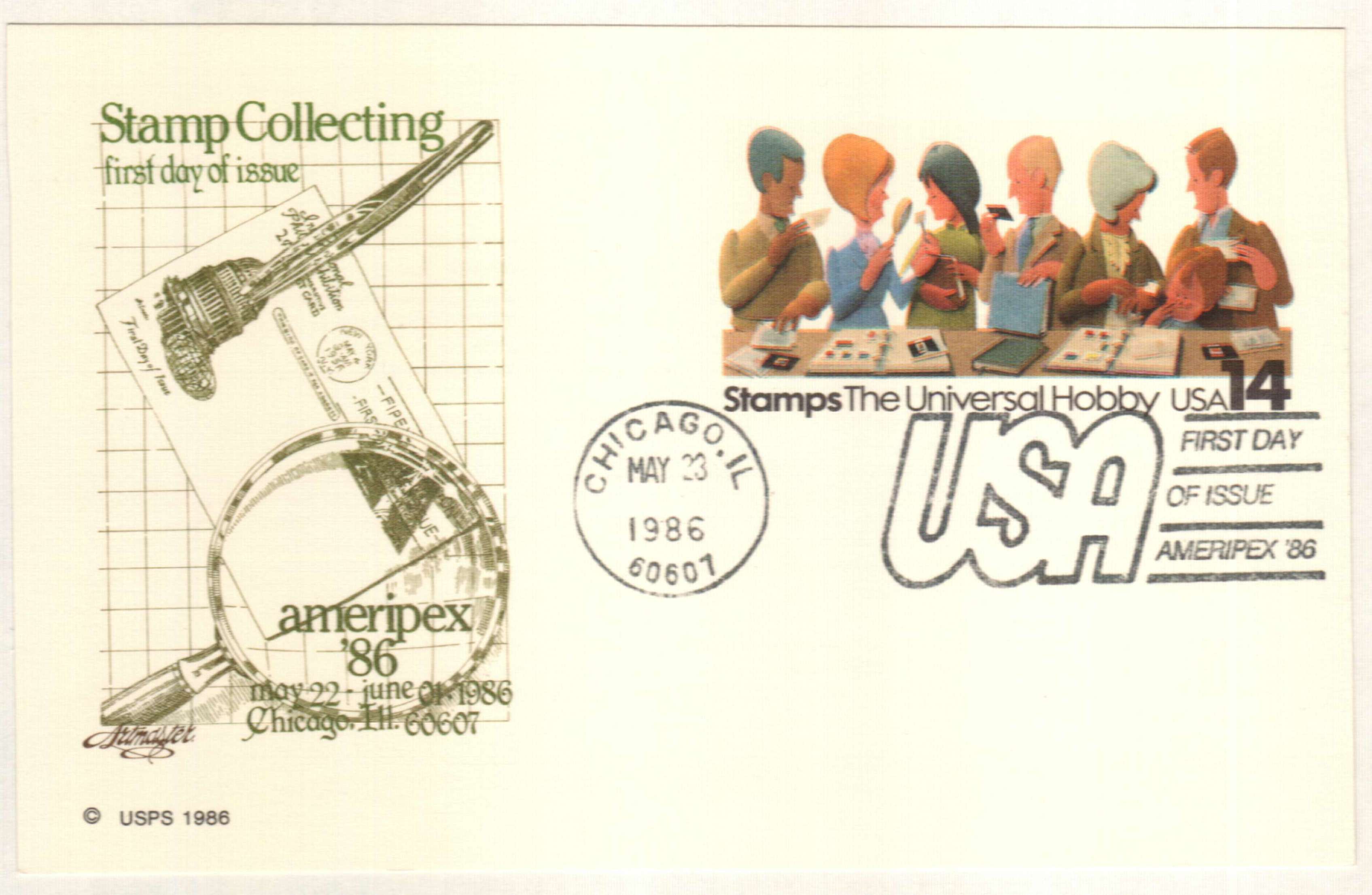

To promote the use of the agency, many philatelic publications shared important information about how to order stamps. People requesting stamps had to send cash or a money order to pay for the stamps they wanted as well as the return postage. Additionally, the agency became aware that some older and rarer issues were still held at smaller post offices around the country. So they requested that those post offices return those stamps so they could be made available to collectors. Regardless of rarity, all stamps available from the Philatelic Agency were sold at face value.

Up until this time, catering to special philatelic requests and answering collectors’ questions had become a full-time job, and postal clerks had little time for their regular duties. By organizing such a division, it was hoped that both regular patrons’ and collectors’ requests would be handled accurately and promptly. The primary function of the department was to fill orders for items such as well-centered stamps, plate blocks, and other special philatelic material.

While many people were happy with the services provided by the Philatelic Agency, not all agreed. The American Philatelist claimed that such agencies (there were over 100 similar agencies in other countries around the world) took away the excitement of tracking down a rare stamp and made collecting too easy.

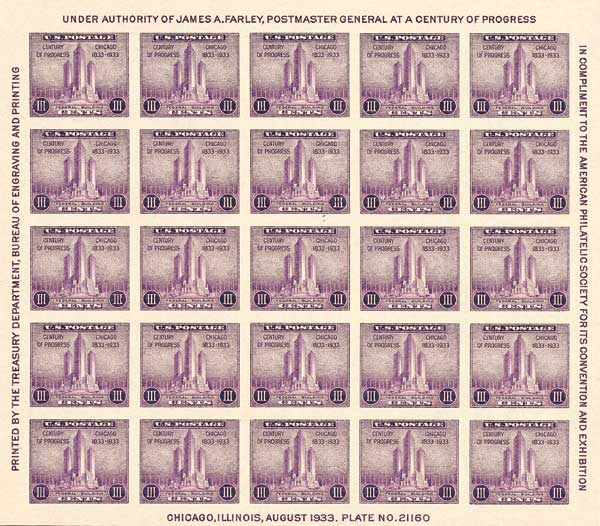

At the time the project was begun, many thought it would never amount to much and was a waste of money. But during its first seven months in operation, the agency made $20,000. The following year they made over $105,000. And by the mid-1930s, they made over $1 million each year. That was quite a feat, considering these sales continued as America made its way through the Great Depression.

With the creation of this agency, the Department also began to distribute advance information on new issues, lists of stamps in stock, and other news, which was of interest to collectors. In addition, publication releases were prepared for use by the press and stamp journals.

During its first few years in operation, the agency was flooded with requests for stamps. Some collectors were upset that they didn’t receive their stamps back quickly. But as the agency explained, each request was numbered upon arrival and then filled in that order. Some requests were quite large and might require significant research and labor. To help meet the needs of collectors, the agency was expanded and restructured in 1924.

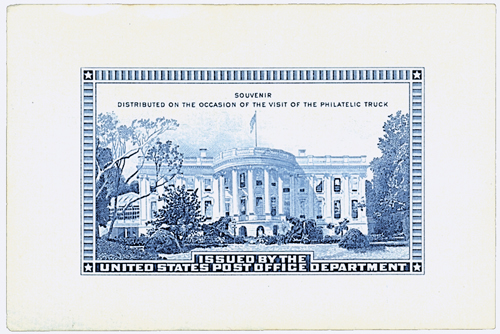

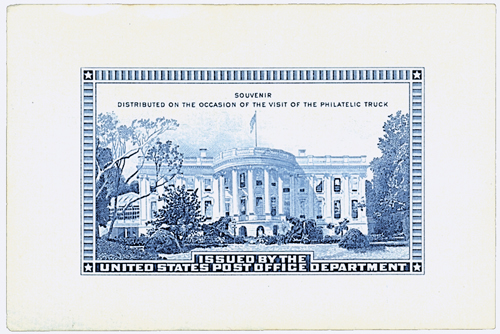

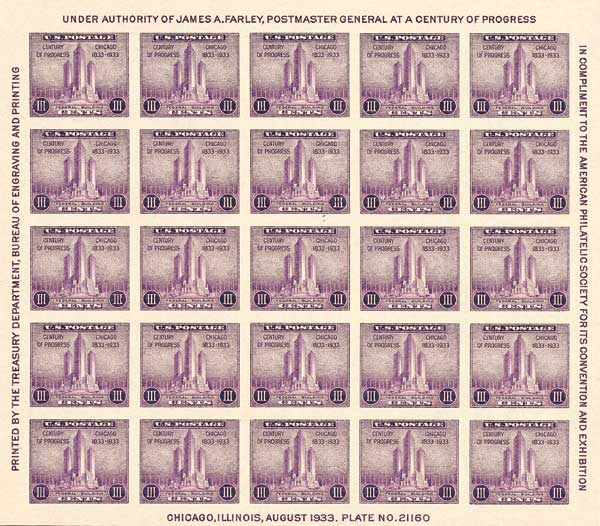

In 1935, the agency opened its own stamp museum across the hall from its offices. While the Post Office Department had donated most of its collection to the Smithsonian years earlier, they had saved many stamps and wanted to put them on display. They requested stamps from local post offices and foreign governments to help fill their museum as well. Postmaster General James Farley said that this museum was an “important research center for collectors.”

Eventually, the Philatelic Agency became the Philatelic Sales Unit. In 1965, the office was closed and its operations were transferred to a sales unit at the Washington, DC, Post Office. Then in 1971, the work was taken over by the Philatelic Sales Unit.

The USPOD Philatelic Agency

On December 1, 1921, the US Post Office Department opened its Philatelic Agency in Washington, DC, to the benefit of stamp collectors.

By the 1920s, stamp collecting had grown to be very popular both in the US and around the world. In spite of that popularity, the number of post offices in the country had dropped from over 76,000 in 1900 to about 52,000 in 1920. Collectors and dealers began writing directly to the Post Office Department to request harder to find stamps.

In 1917 a congressman who was also a collector recommended the creation of the Philatelic Agency. Soon others agreed, as creating this new office would allow the Post Office to expand its commemorative stamp program and keep track of the sales. They believed such an agency could help to consistently fund the Post Office Department and encourage stamp collecting. The Philatelic Agency was officially established on December 1, 1921.

The Postmaster General stated that the agency gave formal recognition to “the growing importance of stamp collecting” and that it would help both collectors and dealers. Mekeel’s Weekly, which had also requested such a move, saw this act as “humanizing the department.” To collectors, it indicated that the Postal Department took their efforts seriously and realized their growing importance.

To promote the use of the agency, many philatelic publications shared important information about how to order stamps. People requesting stamps had to send cash or a money order to pay for the stamps they wanted as well as the return postage. Additionally, the agency became aware that some older and rarer issues were still held at smaller post offices around the country. So they requested that those post offices return those stamps so they could be made available to collectors. Regardless of rarity, all stamps available from the Philatelic Agency were sold at face value.

Up until this time, catering to special philatelic requests and answering collectors’ questions had become a full-time job, and postal clerks had little time for their regular duties. By organizing such a division, it was hoped that both regular patrons’ and collectors’ requests would be handled accurately and promptly. The primary function of the department was to fill orders for items such as well-centered stamps, plate blocks, and other special philatelic material.

While many people were happy with the services provided by the Philatelic Agency, not all agreed. The American Philatelist claimed that such agencies (there were over 100 similar agencies in other countries around the world) took away the excitement of tracking down a rare stamp and made collecting too easy.

At the time the project was begun, many thought it would never amount to much and was a waste of money. But during its first seven months in operation, the agency made $20,000. The following year they made over $105,000. And by the mid-1930s, they made over $1 million each year. That was quite a feat, considering these sales continued as America made its way through the Great Depression.

With the creation of this agency, the Department also began to distribute advance information on new issues, lists of stamps in stock, and other news, which was of interest to collectors. In addition, publication releases were prepared for use by the press and stamp journals.

During its first few years in operation, the agency was flooded with requests for stamps. Some collectors were upset that they didn’t receive their stamps back quickly. But as the agency explained, each request was numbered upon arrival and then filled in that order. Some requests were quite large and might require significant research and labor. To help meet the needs of collectors, the agency was expanded and restructured in 1924.

In 1935, the agency opened its own stamp museum across the hall from its offices. While the Post Office Department had donated most of its collection to the Smithsonian years earlier, they had saved many stamps and wanted to put them on display. They requested stamps from local post offices and foreign governments to help fill their museum as well. Postmaster General James Farley said that this museum was an “important research center for collectors.”

Eventually, the Philatelic Agency became the Philatelic Sales Unit. In 1965, the office was closed and its operations were transferred to a sales unit at the Washington, DC, Post Office. Then in 1971, the work was taken over by the Philatelic Sales Unit.