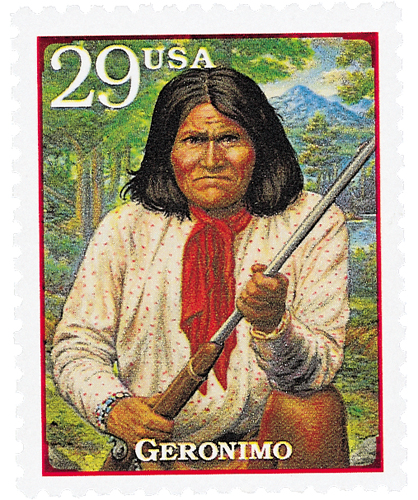

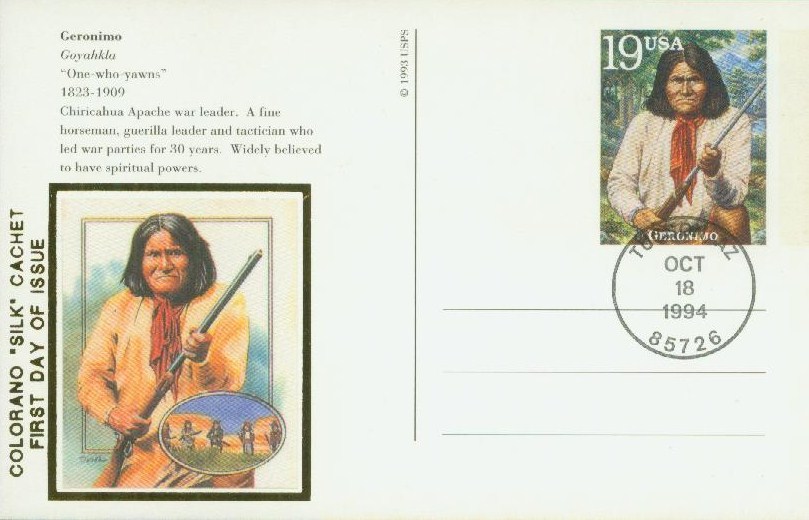

# UX190 - 1994 19c Geronimo Postal Card

Â

Â

Death Of Apache Warrior Geronimo

After decades of fighting to return to his homeland, Geronimo died on February 17, 1909, never able to realize his wish.

Geronimo was born on June 16, 1829, in present-day Arizona, in a region claimed by both Mexico and the Apache Indians. A Chiricahua Apache, Geronimo’s given Native American name was Goyaalé – “the one who yawns.†A talented hunter, he claimed to have swallowed the heart of his first kill to guarantee a successful life on the run. Coming from a small tribe of just 8,000 Apaches, he was often surrounded by enemies and proved to be a talented raider – leading four successful raids by the time he was 17.

That same year, Geronimo married a woman named Alope and began a family. In 1851, while Geronimo and other men of his tribe were in town trading goods, a band of Mexicans attacked their camp. Geronimo’s mother, wife and all three of his children were killed – unleashing a fury that would drive him to destroy his enemies. When U.S. troops and settlers began moving in on Apache land, Geronimo fought back with the same vengeance. Although he was outnumbered, Geronimo fought for over thirty years, becoming famous for his bravery and cunning. He was described as having the “eye of a hawk, the stealth of a coyote, and the courage of a tiger.â€

During one battle he repeatedly ran through a hail of bullets to kill Mexican soldiers with his knife. Seeing the warrior running towards them, the soldiers began to yell out “Geronimo!†– most likely a plea to St. Jerome to spare their lives, though possibly a mispronunciation of his given name.

In 1876, the Chiricahuas were moved to a reservation in San Carlos, Arizona. But Geronimo, refusing to give up his freedom, fled with 700 followers. One of the most feared and respected Indian warriors, Geronimo fought overwhelming odds in trying to win freedom for his people. He eluded the authorities for nearly ten years. During that time he faked surrender on three occasions, but fled at the last moment.

But by the late 1880s, his band included only 38 men, women and children. After decades of fighting and years of running dozens of miles a day, Geronimo and his followers were tired. In September 1886, Geronimo surrendered for the fourth and last time, after more than 5,000 troops had been deployed against him. He was the last Indian warrior to do so, ending the major fighting in the Indian Wars in the Southwest.

Geronimo spent several years as a prisoner of war in Florida and Alabama. In 1894, Geronimo and his followers were moved to Fort Sill, Oklahoma and given farmland on the Kiowa Comanche Reservation. Four years later, he was part of a delegation that attended the Trans-Mississippi International Exposition in Nebraska. Americans had learned about Geronimo’s exploits during the Apache Wars and were curious to see the warrior in person. Geronimo quickly achieved celebrity status there and was frequently invited to subsequent fairs in the coming years. Among the largest were the Pan-American Expo in New York and the Louisiana Purchase Expo in Missouri. Geronimo attended these expos in his traditional warrior clothing, posed for pictures, and sold his crafts.

Geronimo met President Theodore Roosevelt in 1904, and was among a group of Indian chiefs to ride in his inaugural parade. Geronimo asked the president to allow his people to return to their homeland in Arizona, but Roosevelt refused, as tensions were still high from casualties his people inflicted decades earlier. Five years later, Geronimo was thrown from his horse while riding home and spent the night out in the cold. Though a friend found him the next morning and brought him home, Geronimo was in poor health and he died six days later on February 17, 1909. In his final days he admitted, “I should never have surrendered. I should have fought until I was the last man alive.

Â

Â

Death Of Apache Warrior Geronimo

After decades of fighting to return to his homeland, Geronimo died on February 17, 1909, never able to realize his wish.

Geronimo was born on June 16, 1829, in present-day Arizona, in a region claimed by both Mexico and the Apache Indians. A Chiricahua Apache, Geronimo’s given Native American name was Goyaalé – “the one who yawns.†A talented hunter, he claimed to have swallowed the heart of his first kill to guarantee a successful life on the run. Coming from a small tribe of just 8,000 Apaches, he was often surrounded by enemies and proved to be a talented raider – leading four successful raids by the time he was 17.

That same year, Geronimo married a woman named Alope and began a family. In 1851, while Geronimo and other men of his tribe were in town trading goods, a band of Mexicans attacked their camp. Geronimo’s mother, wife and all three of his children were killed – unleashing a fury that would drive him to destroy his enemies. When U.S. troops and settlers began moving in on Apache land, Geronimo fought back with the same vengeance. Although he was outnumbered, Geronimo fought for over thirty years, becoming famous for his bravery and cunning. He was described as having the “eye of a hawk, the stealth of a coyote, and the courage of a tiger.â€

During one battle he repeatedly ran through a hail of bullets to kill Mexican soldiers with his knife. Seeing the warrior running towards them, the soldiers began to yell out “Geronimo!†– most likely a plea to St. Jerome to spare their lives, though possibly a mispronunciation of his given name.

In 1876, the Chiricahuas were moved to a reservation in San Carlos, Arizona. But Geronimo, refusing to give up his freedom, fled with 700 followers. One of the most feared and respected Indian warriors, Geronimo fought overwhelming odds in trying to win freedom for his people. He eluded the authorities for nearly ten years. During that time he faked surrender on three occasions, but fled at the last moment.

But by the late 1880s, his band included only 38 men, women and children. After decades of fighting and years of running dozens of miles a day, Geronimo and his followers were tired. In September 1886, Geronimo surrendered for the fourth and last time, after more than 5,000 troops had been deployed against him. He was the last Indian warrior to do so, ending the major fighting in the Indian Wars in the Southwest.

Geronimo spent several years as a prisoner of war in Florida and Alabama. In 1894, Geronimo and his followers were moved to Fort Sill, Oklahoma and given farmland on the Kiowa Comanche Reservation. Four years later, he was part of a delegation that attended the Trans-Mississippi International Exposition in Nebraska. Americans had learned about Geronimo’s exploits during the Apache Wars and were curious to see the warrior in person. Geronimo quickly achieved celebrity status there and was frequently invited to subsequent fairs in the coming years. Among the largest were the Pan-American Expo in New York and the Louisiana Purchase Expo in Missouri. Geronimo attended these expos in his traditional warrior clothing, posed for pictures, and sold his crafts.

Geronimo met President Theodore Roosevelt in 1904, and was among a group of Indian chiefs to ride in his inaugural parade. Geronimo asked the president to allow his people to return to their homeland in Arizona, but Roosevelt refused, as tensions were still high from casualties his people inflicted decades earlier. Five years later, Geronimo was thrown from his horse while riding home and spent the night out in the cold. Though a friend found him the next morning and brought him home, Geronimo was in poor health and he died six days later on February 17, 1909. In his final days he admitted, “I should never have surrendered. I should have fought until I was the last man alive.