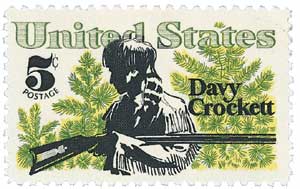

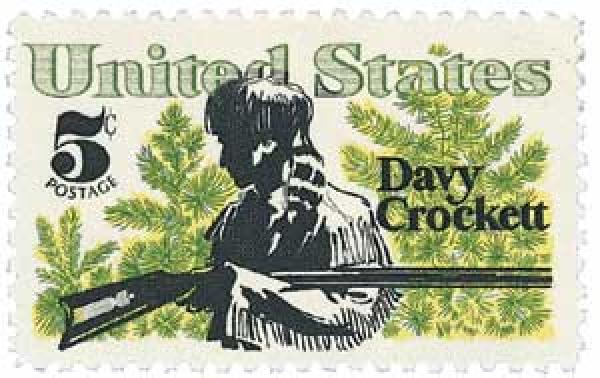

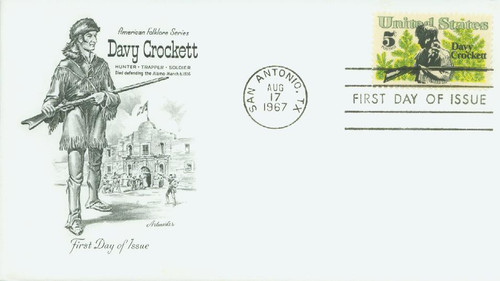

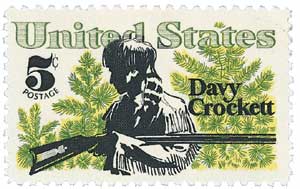

# 1330e - 1967 5c Davy Crockett and Scrub

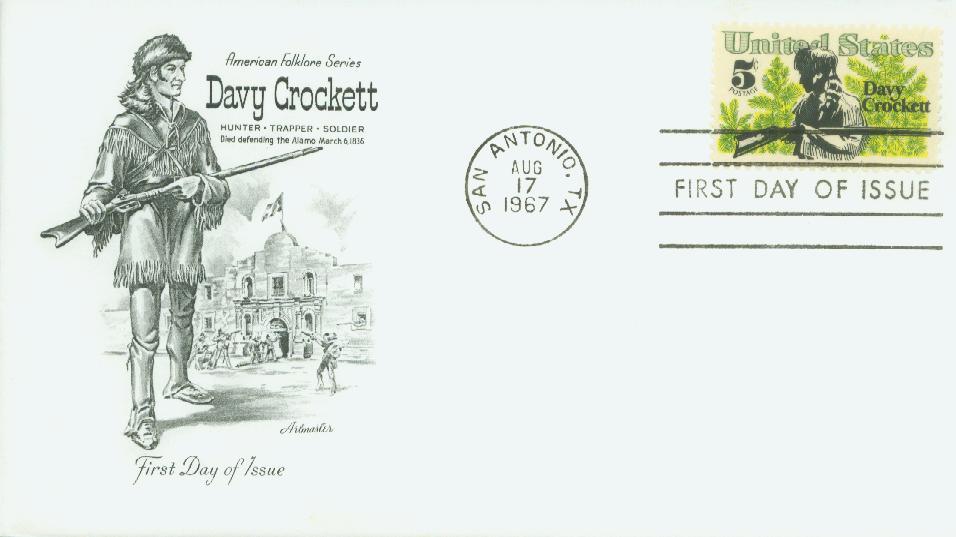

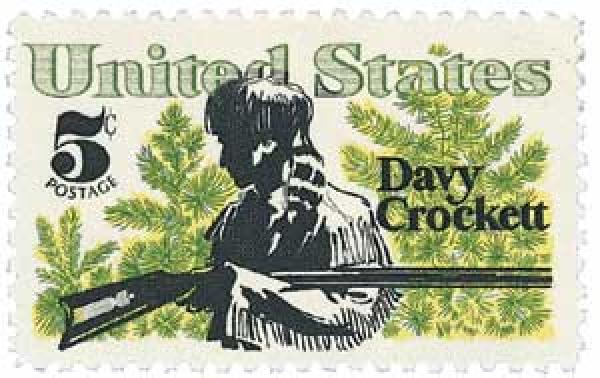

US #1330e Tagging Omitted

1967 5¢ Davy Crockett

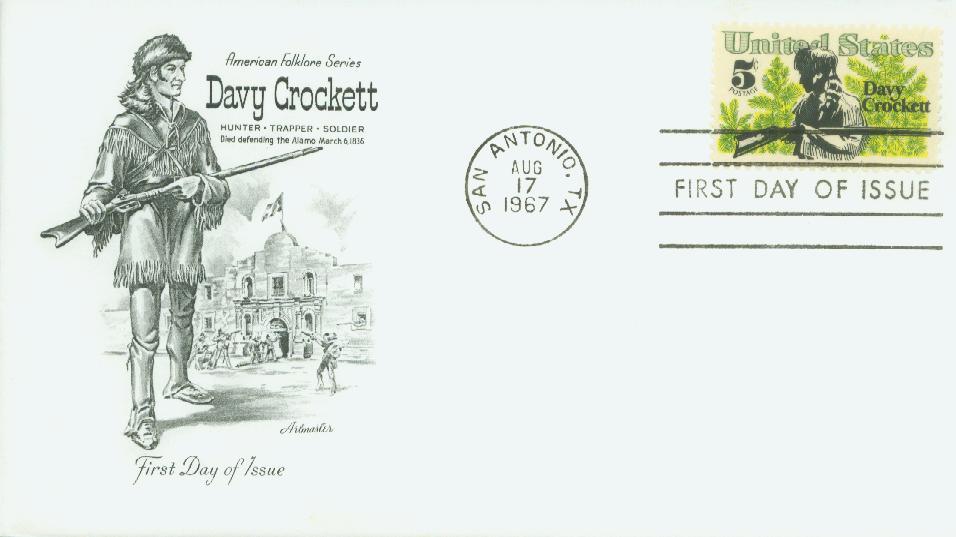

Issue Date: August 17, 1967

City: San Antonio, TX

Printed By: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Lithograph, Engraved

Perforations: 11

Color: Green, black and yellow

What is Phosphorescent Tagging and Why is it Important?

Tagging of U.S. stamps was introduced in 1963 with airmail stamp #C64a. It helps the U.S. Post Office use automation to move the mail at a lower cost. A virtually invisible phosphorescent material is applied either to stamp ink or paper, or to stamps after printing. This “taggant” causes each one to glow in shades of green (red on older airmails) for a moment after exposure to short-wave ultraviolet (UV) light. The afterglow makes it possible for facing-canceling machines to locate the stamp on the mail piece, and properly position it for automated cancellation and sorting.

Some stamps have been printed with and without tagging intentionally, but when tagging is omitted by accident, we collectors are treated to a scarce modern color error. Our stamp experts examined thousands of stamps to find these just for you. Now you can easily give your error collection a boost or explore this fascinating new area of collecting. Quantities are limited, so order your untagged error stamp right away.

And find more tagging omitted stamps here.

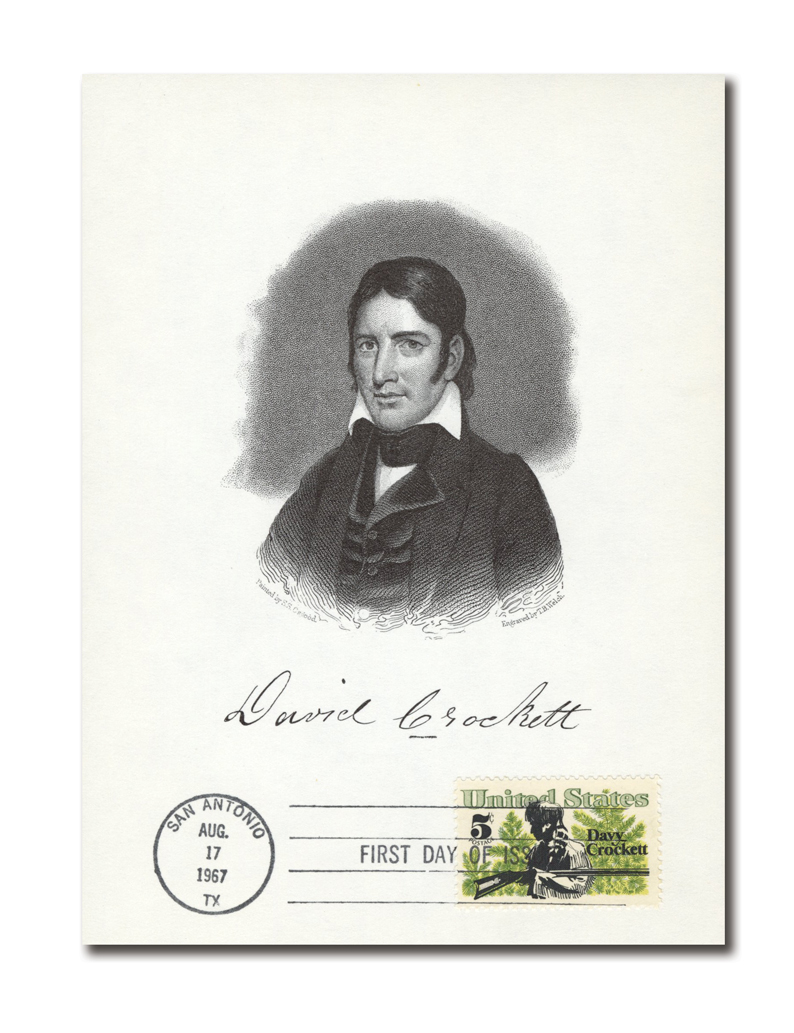

Happy Birthday Davy Crockett

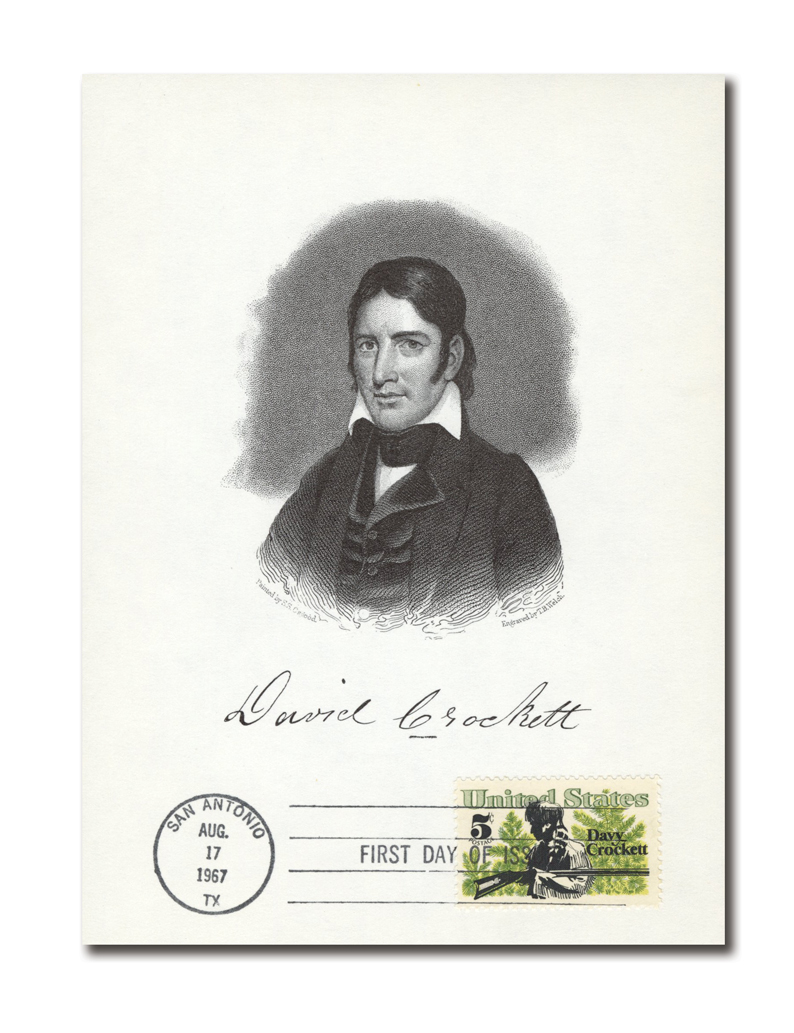

David “Davy” Crockett was born on August 17, 1786 in Greene County, North Carolina (though it is now part of Tennessee). Dubbed the King of the Wild Frontier, Crockett was a folk hero, politician, frontiersman and soldier. Crockett’s ancestral name was Crocketagne, which his ancestors changed when they emigrated from France to Ireland. For the first few years of his life, Crockett’s family moved frequently as his father struggled to support his family with a gristmill and later a homestead. After declaring bankruptcy, he eventually built a tavern along a stagecoach road. When Crockett was 12, his father hired him out to help make money for the family. Crockett worked as a cowboy, herding cattle along a 400-mile trip to Virginia. The following year Crockett’s father sent him to school, but it didn’t last long. Crockett frequently skipped classes, and when his father found out, he intended to punish him. However, Crockett was faster than his father and ran away. On his own at just 13 years old, Crockett joined a cattle drive to Virginia. He did additional trips and worked for a farmer before returning home in 1802. Crockett worked off more of his father’s debts before he ultimately accepted a paying job for himself with one of his recent employers. In his spare time, Crockett entered local shooting contests where he paid twenty-five cents for a chance at a quarter of beef. His marksmanship was so good that often he won the entire cow! In the coming years, Crockett married, had three children, and remarried after the death of his first wife. In 1813, he joined a regiment of mounted riflemen as a scout to fight in the Creek War in Alabama. Though he participated in the fighting, he preferred hunting game for the soldiers to eat. Crockett returned home that December, but reenlisted the following year to aid in removing British forces from Spanish Florida. He saw little action but again enjoyed spending his time finding food for everyone. In 1817, Crockett began his political career when he moved to Lawrence County, and worked as a commissioner helping to establish the county’s boundaries. Later that year he was made justice of the peace. The following year Crockett was elected lieutenant colonel of the 57th Regiment of Tennessee Militia. However, by 1819 he was running several businesses and felt he didn’t have enough time to devote to his family, so he resigned from his public duties. Crockett returned to public service in 1821 when he won a seat in the Tennessee General Assembly. In that role he served on the Committee of Propositions and Grievances. He supported legislation to lower taxes for the poor and often fought for the rights of impoverished settlers. Though he lost his bid for a seat in the House of Representatives in 1825, Crockett tried again and succeeded in 1827. Serving two terms, Crockett proposed abolishing the US Military Academy at West Point (because he felt it used public money to aid the sons of the wealthy), and introduced a failed amendment to the land bill. Additionally, he opposed President Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act and was the only member of the Tennessee delegate to do so. The people of his district didn’t like this and he lost the next election. He ran again two years later, and won a third and final term in 1833. During this time, Crockett claimed that if Jackson’s successor, Martin Van Buren, was elected president, he’d move to Texas, believing Van Buren would continue the same policies of forced removal. Crockett wrote, “I will consider that government a Paridice to what this will be. In fact at this time our Republican Government has dwindled almost into insignificancy our [boasted] land of liberty have almost Bowed to the yoke of [sic] Bondage.” He believed a revolution was brewing in Texas and wanted to raise a company of volunteers. Eventually, before Van Buren was even elected, Crockett set out for Texas with 30 men. In early February 1836, he joined about 100 Texians garrisoned at the Alamo, an old Roman Catholic mission that had been converted into a military fort. As a Mexican force of about 1,500 approached, additional forces were requested, but no more than 100 men arrived to support the defense. The Mexican troops surrounded and began a siege of the Alamo. Two weeks later on March 6, 1836, after additional Mexican soldiers arrived, bringing their forces to between 3,500 and 6,000 men, the Mexicans began their assault on the fort. All of the defenders, including Crockett, were killed. Many legends surround Davy Crockett, who was a master storyteller with a gift for exaggeration. Crockett told a story about a raccoon that gave up when he spotted him on a hunt. He also claimed to kill 105 bears in just seven months. One fictionalized account of Crockett claimed he could “run faster, jump higher, squat lower, dive deeper, stay under longer, and come out drier than any man in the whole country.”

US #1330e Tagging Omitted

1967 5¢ Davy Crockett

Issue Date: August 17, 1967

City: San Antonio, TX

Printed By: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Lithograph, Engraved

Perforations: 11

Color: Green, black and yellow

What is Phosphorescent Tagging and Why is it Important?

Tagging of U.S. stamps was introduced in 1963 with airmail stamp #C64a. It helps the U.S. Post Office use automation to move the mail at a lower cost. A virtually invisible phosphorescent material is applied either to stamp ink or paper, or to stamps after printing. This “taggant” causes each one to glow in shades of green (red on older airmails) for a moment after exposure to short-wave ultraviolet (UV) light. The afterglow makes it possible for facing-canceling machines to locate the stamp on the mail piece, and properly position it for automated cancellation and sorting.

Some stamps have been printed with and without tagging intentionally, but when tagging is omitted by accident, we collectors are treated to a scarce modern color error. Our stamp experts examined thousands of stamps to find these just for you. Now you can easily give your error collection a boost or explore this fascinating new area of collecting. Quantities are limited, so order your untagged error stamp right away.

And find more tagging omitted stamps here.

Happy Birthday Davy Crockett

David “Davy” Crockett was born on August 17, 1786 in Greene County, North Carolina (though it is now part of Tennessee). Dubbed the King of the Wild Frontier, Crockett was a folk hero, politician, frontiersman and soldier. Crockett’s ancestral name was Crocketagne, which his ancestors changed when they emigrated from France to Ireland. For the first few years of his life, Crockett’s family moved frequently as his father struggled to support his family with a gristmill and later a homestead. After declaring bankruptcy, he eventually built a tavern along a stagecoach road. When Crockett was 12, his father hired him out to help make money for the family. Crockett worked as a cowboy, herding cattle along a 400-mile trip to Virginia. The following year Crockett’s father sent him to school, but it didn’t last long. Crockett frequently skipped classes, and when his father found out, he intended to punish him. However, Crockett was faster than his father and ran away. On his own at just 13 years old, Crockett joined a cattle drive to Virginia. He did additional trips and worked for a farmer before returning home in 1802. Crockett worked off more of his father’s debts before he ultimately accepted a paying job for himself with one of his recent employers. In his spare time, Crockett entered local shooting contests where he paid twenty-five cents for a chance at a quarter of beef. His marksmanship was so good that often he won the entire cow! In the coming years, Crockett married, had three children, and remarried after the death of his first wife. In 1813, he joined a regiment of mounted riflemen as a scout to fight in the Creek War in Alabama. Though he participated in the fighting, he preferred hunting game for the soldiers to eat. Crockett returned home that December, but reenlisted the following year to aid in removing British forces from Spanish Florida. He saw little action but again enjoyed spending his time finding food for everyone. In 1817, Crockett began his political career when he moved to Lawrence County, and worked as a commissioner helping to establish the county’s boundaries. Later that year he was made justice of the peace. The following year Crockett was elected lieutenant colonel of the 57th Regiment of Tennessee Militia. However, by 1819 he was running several businesses and felt he didn’t have enough time to devote to his family, so he resigned from his public duties. Crockett returned to public service in 1821 when he won a seat in the Tennessee General Assembly. In that role he served on the Committee of Propositions and Grievances. He supported legislation to lower taxes for the poor and often fought for the rights of impoverished settlers. Though he lost his bid for a seat in the House of Representatives in 1825, Crockett tried again and succeeded in 1827. Serving two terms, Crockett proposed abolishing the US Military Academy at West Point (because he felt it used public money to aid the sons of the wealthy), and introduced a failed amendment to the land bill. Additionally, he opposed President Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act and was the only member of the Tennessee delegate to do so. The people of his district didn’t like this and he lost the next election. He ran again two years later, and won a third and final term in 1833. During this time, Crockett claimed that if Jackson’s successor, Martin Van Buren, was elected president, he’d move to Texas, believing Van Buren would continue the same policies of forced removal. Crockett wrote, “I will consider that government a Paridice to what this will be. In fact at this time our Republican Government has dwindled almost into insignificancy our [boasted] land of liberty have almost Bowed to the yoke of [sic] Bondage.” He believed a revolution was brewing in Texas and wanted to raise a company of volunteers. Eventually, before Van Buren was even elected, Crockett set out for Texas with 30 men. In early February 1836, he joined about 100 Texians garrisoned at the Alamo, an old Roman Catholic mission that had been converted into a military fort. As a Mexican force of about 1,500 approached, additional forces were requested, but no more than 100 men arrived to support the defense. The Mexican troops surrounded and began a siege of the Alamo. Two weeks later on March 6, 1836, after additional Mexican soldiers arrived, bringing their forces to between 3,500 and 6,000 men, the Mexicans began their assault on the fort. All of the defenders, including Crockett, were killed. Many legends surround Davy Crockett, who was a master storyteller with a gift for exaggeration. Crockett told a story about a raccoon that gave up when he spotted him on a hunt. He also claimed to kill 105 bears in just seven months. One fictionalized account of Crockett claimed he could “run faster, jump higher, squat lower, dive deeper, stay under longer, and come out drier than any man in the whole country.”