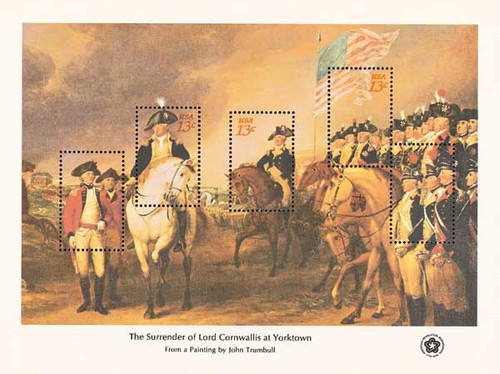

# 1686 - 1976 Surrender at Yorktown

Birth Of Baron Von Steuben

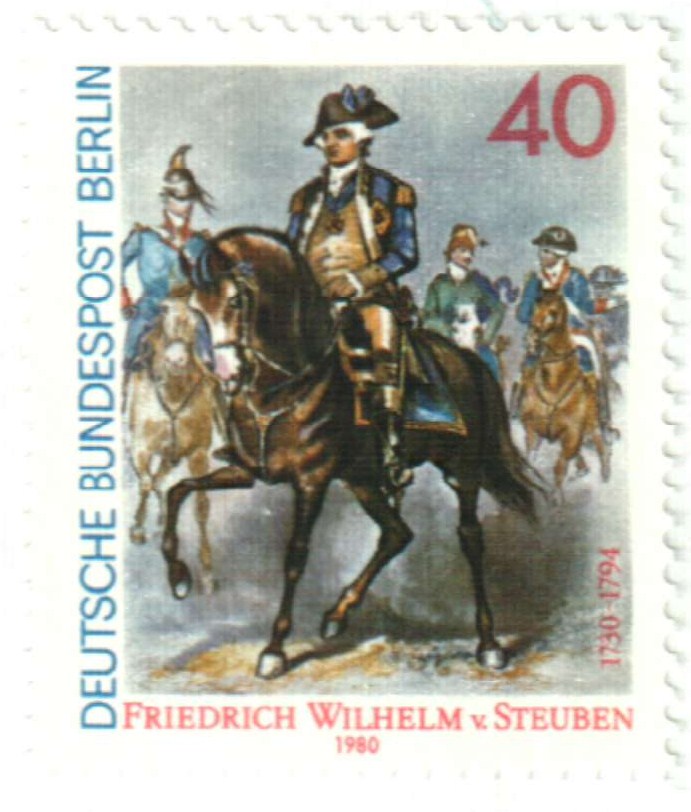

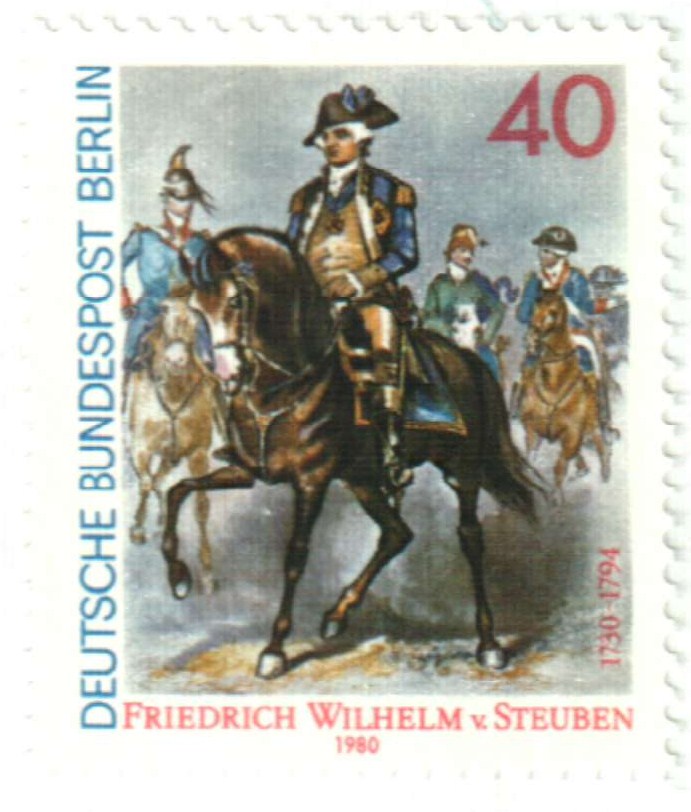

Wilhelm von Steuben was born on September 17, 1730, in Magdeburg, Kingdom of Prussia (present-day Germany).

Von Steuben was the son of a Prussian engineer captain. He traveled with his father during the Russo-Turkish War before returning to Prussia where he attended school.

Von Steuben joined the Prussian Army when he was 17 and participated in the Seven Years’ War before being wounded at the Battle of Prague and later the Battle of Kunersdorf. In 1761 he was taken prisoner by the Russians at Treptow and upon his release, was promoted to captain. Von Steuben then served as aide-de-camp to Frederick the Great. He was one of just 13 young officers to study with the king.

After the war, the army was reduced and von Steuben was released from his service. In 1777, the French Minister of War (whom he’d met years earlier) introduced von Steuben to Benjamin Franklin in Paris. Franklin told von Steuben that he couldn’t offer him a high rank or pay, but with few other options, von Steuben opted to travel to America to join in their cause.

Franklin sent a letter to George Washington introducing von Steuben as a “Lieutenant General in the King of Prussia’s service,” an inaccurate statement likely based on a mistranslation. Regardless, he was awarded travel funds and departed Europe on September 26, 177.

Von Steuben reached Portsmouth, New Hampshire on December 1, 1777. He, his aide-de-camp, military secretary, and two other companions were nearly arrested because they unknowingly wore red uniforms. They then received a grand welcome in Boston before traveling to York, Pennsylvania, where the Continental Congress had convened after being removed from Philadelphia.

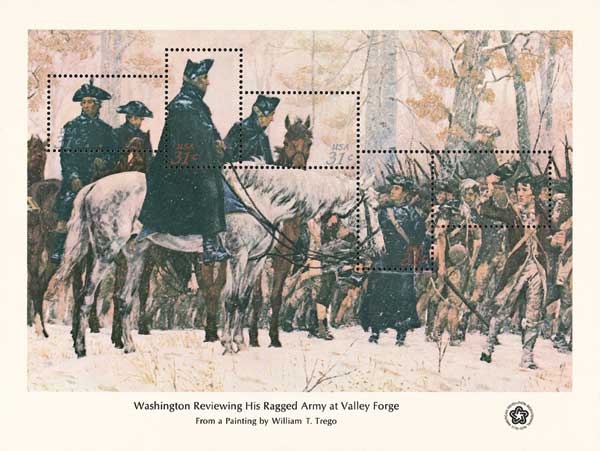

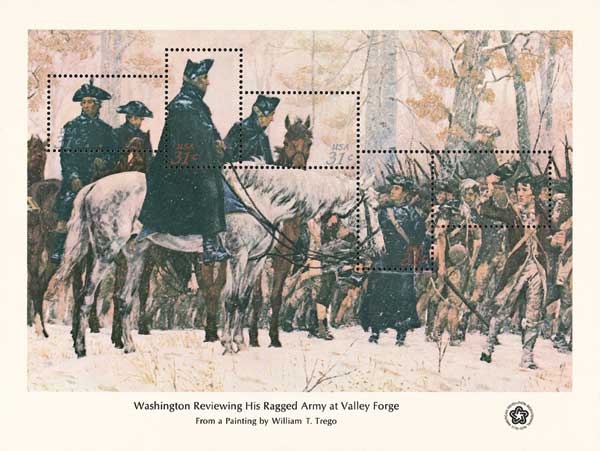

Von Steuben reported to Valley Forge as a volunteer on February 23, 1778, after which Washington made him temporary inspector general. Three months later he was made inspector general of the army. In this service, he explored the camp and made recommendations. Up until that time, tents and huts weren’t arranged in a specific manner, and conditions were not very sanitary. Von Steuben recommended that the tents be organized by command and that kitchens and latrines be located on opposite sides of the camp. The Army would use Von Steuben’s improvements for over 150 years. He also improved the army’s administration, insisting they keep exact records and perform strict inspections, saving the army from an estimated loss of 8,000 muskets that might previously have been claimed by war profiteering or other issues.

Von Steuben was also put in charge of training soldiers. He selected 120 men from different regiments to form an honor guard that would then train the other troops. He spoke little English, so when he was frustrated, he would call to his translator, “Over here! Swear at him for me!” His ability to swear in multiple languages, and his willingness to work with the men, made him very popular.

Despite the colorful language, von Steuben’s system of training worked well. His Revolutionary War Drill Manual was used by the American military until the War of 1812. His bayonet training was especially valuable to an army short on ammunition. At Stony Point, Americans fought with just the bayonets of unloaded muskets and won thanks to his training. He later commanded one of the divisions at Yorktown and as the war ended, helped Washington plan the new nation’s defense.

After the war, von Steuben became a citizen of the United States and a prominent resident in Manhattan. He served as president of the German Society of the City of New York, which helped German immigrants. He later settled near Utica, New York, on land granted to him for his military service. He died there on November 28, 1794. His estate later became part of the town of Steuben, which was named in his honor. A number of counties, cities, buildings, and ships have been named in his honor. There’s also the Steuben Society and the annual Von Steuben Day, held on a weekend in mid-September.

Birth Of Baron Von Steuben

Wilhelm von Steuben was born on September 17, 1730, in Magdeburg, Kingdom of Prussia (present-day Germany).

Von Steuben was the son of a Prussian engineer captain. He traveled with his father during the Russo-Turkish War before returning to Prussia where he attended school.

Von Steuben joined the Prussian Army when he was 17 and participated in the Seven Years’ War before being wounded at the Battle of Prague and later the Battle of Kunersdorf. In 1761 he was taken prisoner by the Russians at Treptow and upon his release, was promoted to captain. Von Steuben then served as aide-de-camp to Frederick the Great. He was one of just 13 young officers to study with the king.

After the war, the army was reduced and von Steuben was released from his service. In 1777, the French Minister of War (whom he’d met years earlier) introduced von Steuben to Benjamin Franklin in Paris. Franklin told von Steuben that he couldn’t offer him a high rank or pay, but with few other options, von Steuben opted to travel to America to join in their cause.

Franklin sent a letter to George Washington introducing von Steuben as a “Lieutenant General in the King of Prussia’s service,” an inaccurate statement likely based on a mistranslation. Regardless, he was awarded travel funds and departed Europe on September 26, 177.

Von Steuben reached Portsmouth, New Hampshire on December 1, 1777. He, his aide-de-camp, military secretary, and two other companions were nearly arrested because they unknowingly wore red uniforms. They then received a grand welcome in Boston before traveling to York, Pennsylvania, where the Continental Congress had convened after being removed from Philadelphia.

Von Steuben reported to Valley Forge as a volunteer on February 23, 1778, after which Washington made him temporary inspector general. Three months later he was made inspector general of the army. In this service, he explored the camp and made recommendations. Up until that time, tents and huts weren’t arranged in a specific manner, and conditions were not very sanitary. Von Steuben recommended that the tents be organized by command and that kitchens and latrines be located on opposite sides of the camp. The Army would use Von Steuben’s improvements for over 150 years. He also improved the army’s administration, insisting they keep exact records and perform strict inspections, saving the army from an estimated loss of 8,000 muskets that might previously have been claimed by war profiteering or other issues.

Von Steuben was also put in charge of training soldiers. He selected 120 men from different regiments to form an honor guard that would then train the other troops. He spoke little English, so when he was frustrated, he would call to his translator, “Over here! Swear at him for me!” His ability to swear in multiple languages, and his willingness to work with the men, made him very popular.

Despite the colorful language, von Steuben’s system of training worked well. His Revolutionary War Drill Manual was used by the American military until the War of 1812. His bayonet training was especially valuable to an army short on ammunition. At Stony Point, Americans fought with just the bayonets of unloaded muskets and won thanks to his training. He later commanded one of the divisions at Yorktown and as the war ended, helped Washington plan the new nation’s defense.

After the war, von Steuben became a citizen of the United States and a prominent resident in Manhattan. He served as president of the German Society of the City of New York, which helped German immigrants. He later settled near Utica, New York, on land granted to him for his military service. He died there on November 28, 1794. His estate later became part of the town of Steuben, which was named in his honor. A number of counties, cities, buildings, and ships have been named in his honor. There’s also the Steuben Society and the annual Von Steuben Day, held on a weekend in mid-September.