# 1846 - 1983 3c Great Americans: Henry Clay

U.S. #1846

1983 3¢ Henry Clay

Great Americans

- 12th stamp in the Great Americans Series

- Honors the man known as the “Great Compromiser” and “Great Pacificator”

Stamp Category: Definitive

Series: Great Americans

Value: 3¢; used predominantly as a “change maker”

First Day of Issue: July 13, 1983

First Day City: Washington, DC

Quantity Issued: 100,000,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving & Printing

Printing Method: Engraved

Format: Panes of 100

Perforations: 11 x 10.5

Color: Olive green

Why the stamp was issued: To provide a 3¢ sheet stamp for the Great Americans Series. At the time, there was a 3¢ coil stamp in the Transportation Series, but sheet stamps were more commonly used by postal patrons.

When the stamp was issued the postmaster general was asked “What is this great statesman and member of the Senate’s Hall of Fame doing on a rather obscure 3¢ denomination?” The postmaster general responded, “On the contrary, Clay’s memory will be philatelically perpetuated for a much longer time as a definitive issue than it would have been on a 20¢ commemorative of more limited life span.”

The most common use for this stamp was as a “change maker.” As Don McDowell of the Stamps Division pointed out, “When a small post office without a meter machine quotes a parcel post rate of $1.86 to a customer, they’d better have the ‘change maker’ stamps on hand to hit it exactly.” These low denominations were also useful in the event of a rate change.

About the stamp design: Ward Brackett created the stamp image from several different portraits of Clay created around 1845, when the statesman was in his late 60s.

First Day City: The First Day ceremony for this stamp was held in the Old Senate Chamber of the US Capitol Building in Washington, DC. It was in this room that Clay had delivered some of his most important speeches more than a century earlier.

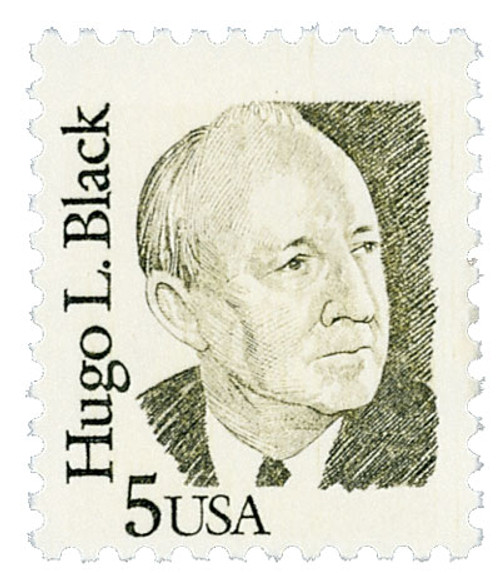

About the Great Americans Series: The Great Americans Series was created to replace the Americana Series. The new series would be characterized by a standard definitive size, simple design, and monochromatic colors.

This simple design included a portrait, “USA,” the denomination, the person’s name, and in some cases, their occupation or reason for recognition. The first stamp in the new series was issued on December 27, 1980. It honored Sequoyah and fulfilled the new international postcard rate that would go into effect in January 1981.

The Great Americans Series would honor a wider range of people than the previous Prominent Americans and Liberty Series. While those series mainly honored presidents and politicians, the Great Americans Series featured people from many fields and ethnicities. They were individuals who were leaders in education, the military, literature, the arts, and human and civil rights. Plus, while the previous series only honored a few women, the Great Americans featured 15 women. This was also the first definitive series to honor Native Americans, with five stamps.

The Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP) produced most of the stamps, but private firms printed some. Several stamps saw multiple printings. The result was many different varieties, with tagging being the key to understanding them. Though there were also differences in perforations, gum, paper, and ink color.

The final stamp in the series was issued on July 17, 1999, honoring Justin S. Morrill. Spanning 20 years, the Great Americans was the longest-running US definitive series. It was also the largest series of face-different stamps, with a total of 63.

Click here for all the individual stamps and click here for the complete series.

History the stamp represents: Henry Clay was born on April 12, 1777, in Hanover County, Virginia. The seventh of nine children, Clay began working as a secretary at the Virginia Court of Chancery at a young age. From there he went on to work for the attorney general, where he developed an interest in and began studying the law. He was admitted to the bar in 1797.

That same year, Clay moved to Lexington, Kentucky, where he quickly became well known for his legal skills and courtroom speeches. Over the years many of his clients paid him with horses and plots of land. By 1812, Clay had a 600-acre plantation known as Ashland.

In 1803 Clay was made a representative of Fayette County in the Kentucky General Assembly, even though he wasn’t old enough to be elected. In this role he supported the attempt to move the state capitol from Frankfort to Lexington. While he publicly supported the gradual end of slavery in Kentucky, but continued to buy and sell people as his wealth grew, owning up to 60 enslaved individuals at his own plantation.

Clay’s popularity rose quickly in the coming years, so that when a US Senate seat needed to be filled, he was selected and sworn in on December 29, 1806. Once again, he was under the required age, but no one objected. He served the last two months of that term before returning to Kentucky in 1807. In 1810, Clay was once again selected to finish out a Senate term, this time for 14 months. However, Clay decided he did not care for the rules of the Senate, and chose to ran for a seat in the US House of Representatives.

Clay was elected and was made speaker of the House on his first day (which has only ever happened one other time). Clay would be re-elected to that position five times in the next 14 years. While in that role, Clay vastly increased its political power, making it second only to the president. Clay initially opposed the creation of a national bank because he personally owned several small banks in Lexington. However, he later changed his stance, offering his support for the Second Bank of the United States when he ran for the presidency.

In 1814, Clay helped negotiate and later signed the Treaty of Ghent, ending the War of 1812. Two years later he worked with John C. Calhoun to pass the Tariff Act of 1816. The act was part of Clay’s national economic plan he called the American System, which was designed to help America compete with British manufacturing through tariffs. These tariffs, as well as the sale of public lands, would then go toward internal improvements such as new roads and canals.

In 1820, tensions between the North and South erupted when Missouri wanted to enter the Union as a slave state. Clay earned his nickname “The Great Compromiser” in developing the Missouri Compromise. This agreement admitted Maine as a free state and permitted slavery in the new state of Missouri, but prohibited it in most of the Louisiana Territory, a huge area west of the Mississippi River. This maintained the balance in the Senate of 11 slave and 11 free states.

Clay was still serving as speaker of the House of Representatives when he campaigned for president in 1824. Four candidates split the field, with no one receiving a majority of Electoral votes. The top three candidates were presented to the House of Representatives to decide the outcome of the election. Clay’s political views were closer to those of John Quincy Adams than Andrew Jackson, and the speaker used his influence to elect Adams. President John Quincy Adams appointed Henry Clay as his secretary of State, a position he’d long desired. Jackson and his supporters called the move a “corrupt bargain.”

As secretary of State, Clay made trade agreements with newly independent Latin American countries. He sought to have the US involved in the Pan-American Congress of 1826, but Congress approved the measure too late. Adams was not reelected for a second term and Clay returned to his home in Kentucky until he was elected to the Senate in 1831. Two years later he worked on the Compromise Tariff of 1833, which lowered tariffs gradually. Between 1832 and 1848, Clay ran for president four more times, but never succeeded. After losing the Whig Party nomination in 1848, he hoped to retire to his Ashland estate. But the following year he was once again elected to the US Senate.

By this time, America had received new land following the Mexican-American War. The issue of slavery spreading to new territories was again a concern. In response, Clay introduced the Compromise of 1850, which was as controversial as the slavery debate itself. Clay’s bill proposed the organization of the Utah and New Mexico Territories, the admission of California as a free state, and prohibit slave auctions in the District of Columbia. Additionally, the bill would amend the Fugitive Slave Act. This ordered runaway slaves found anywhere in the United States be returned to their masters if a board of commissioners declared them fugitives. The bill would require authorities, including local officials in free states, to arrest Blacks and return them to slave territory. It also eliminated jury trials for those accused of being fugitive slaves and forbid them from testifying in their own defense. President Taylor opposed the compromise, wanting New Mexico to be admitted as a full state immediately, while Vice President Fillmore urged him to pass the bill.

Worn down by the constant fighting and weakened by tuberculosis, Clay left the capital and David Meriwether came in as his replacement. The compromise was ultimately passed after Taylor’s sudden death and Fillmore’s support.

Clay returned to Kentucky to live out his final years at Ashland. He succumbed to tuberculosis on June 29, 1852.

In later years, President Abraham Lincoln said Clay was “my ideal of a great man.” And in 1957, a Senate committee called Clay one of the five greatest US senators in American history.

U.S. #1846

1983 3¢ Henry Clay

Great Americans

- 12th stamp in the Great Americans Series

- Honors the man known as the “Great Compromiser” and “Great Pacificator”

Stamp Category: Definitive

Series: Great Americans

Value: 3¢; used predominantly as a “change maker”

First Day of Issue: July 13, 1983

First Day City: Washington, DC

Quantity Issued: 100,000,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving & Printing

Printing Method: Engraved

Format: Panes of 100

Perforations: 11 x 10.5

Color: Olive green

Why the stamp was issued: To provide a 3¢ sheet stamp for the Great Americans Series. At the time, there was a 3¢ coil stamp in the Transportation Series, but sheet stamps were more commonly used by postal patrons.

When the stamp was issued the postmaster general was asked “What is this great statesman and member of the Senate’s Hall of Fame doing on a rather obscure 3¢ denomination?” The postmaster general responded, “On the contrary, Clay’s memory will be philatelically perpetuated for a much longer time as a definitive issue than it would have been on a 20¢ commemorative of more limited life span.”

The most common use for this stamp was as a “change maker.” As Don McDowell of the Stamps Division pointed out, “When a small post office without a meter machine quotes a parcel post rate of $1.86 to a customer, they’d better have the ‘change maker’ stamps on hand to hit it exactly.” These low denominations were also useful in the event of a rate change.

About the stamp design: Ward Brackett created the stamp image from several different portraits of Clay created around 1845, when the statesman was in his late 60s.

First Day City: The First Day ceremony for this stamp was held in the Old Senate Chamber of the US Capitol Building in Washington, DC. It was in this room that Clay had delivered some of his most important speeches more than a century earlier.

About the Great Americans Series: The Great Americans Series was created to replace the Americana Series. The new series would be characterized by a standard definitive size, simple design, and monochromatic colors.

This simple design included a portrait, “USA,” the denomination, the person’s name, and in some cases, their occupation or reason for recognition. The first stamp in the new series was issued on December 27, 1980. It honored Sequoyah and fulfilled the new international postcard rate that would go into effect in January 1981.

The Great Americans Series would honor a wider range of people than the previous Prominent Americans and Liberty Series. While those series mainly honored presidents and politicians, the Great Americans Series featured people from many fields and ethnicities. They were individuals who were leaders in education, the military, literature, the arts, and human and civil rights. Plus, while the previous series only honored a few women, the Great Americans featured 15 women. This was also the first definitive series to honor Native Americans, with five stamps.

The Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP) produced most of the stamps, but private firms printed some. Several stamps saw multiple printings. The result was many different varieties, with tagging being the key to understanding them. Though there were also differences in perforations, gum, paper, and ink color.

The final stamp in the series was issued on July 17, 1999, honoring Justin S. Morrill. Spanning 20 years, the Great Americans was the longest-running US definitive series. It was also the largest series of face-different stamps, with a total of 63.

Click here for all the individual stamps and click here for the complete series.

History the stamp represents: Henry Clay was born on April 12, 1777, in Hanover County, Virginia. The seventh of nine children, Clay began working as a secretary at the Virginia Court of Chancery at a young age. From there he went on to work for the attorney general, where he developed an interest in and began studying the law. He was admitted to the bar in 1797.

That same year, Clay moved to Lexington, Kentucky, where he quickly became well known for his legal skills and courtroom speeches. Over the years many of his clients paid him with horses and plots of land. By 1812, Clay had a 600-acre plantation known as Ashland.

In 1803 Clay was made a representative of Fayette County in the Kentucky General Assembly, even though he wasn’t old enough to be elected. In this role he supported the attempt to move the state capitol from Frankfort to Lexington. While he publicly supported the gradual end of slavery in Kentucky, but continued to buy and sell people as his wealth grew, owning up to 60 enslaved individuals at his own plantation.

Clay’s popularity rose quickly in the coming years, so that when a US Senate seat needed to be filled, he was selected and sworn in on December 29, 1806. Once again, he was under the required age, but no one objected. He served the last two months of that term before returning to Kentucky in 1807. In 1810, Clay was once again selected to finish out a Senate term, this time for 14 months. However, Clay decided he did not care for the rules of the Senate, and chose to ran for a seat in the US House of Representatives.

Clay was elected and was made speaker of the House on his first day (which has only ever happened one other time). Clay would be re-elected to that position five times in the next 14 years. While in that role, Clay vastly increased its political power, making it second only to the president. Clay initially opposed the creation of a national bank because he personally owned several small banks in Lexington. However, he later changed his stance, offering his support for the Second Bank of the United States when he ran for the presidency.

In 1814, Clay helped negotiate and later signed the Treaty of Ghent, ending the War of 1812. Two years later he worked with John C. Calhoun to pass the Tariff Act of 1816. The act was part of Clay’s national economic plan he called the American System, which was designed to help America compete with British manufacturing through tariffs. These tariffs, as well as the sale of public lands, would then go toward internal improvements such as new roads and canals.

In 1820, tensions between the North and South erupted when Missouri wanted to enter the Union as a slave state. Clay earned his nickname “The Great Compromiser” in developing the Missouri Compromise. This agreement admitted Maine as a free state and permitted slavery in the new state of Missouri, but prohibited it in most of the Louisiana Territory, a huge area west of the Mississippi River. This maintained the balance in the Senate of 11 slave and 11 free states.

Clay was still serving as speaker of the House of Representatives when he campaigned for president in 1824. Four candidates split the field, with no one receiving a majority of Electoral votes. The top three candidates were presented to the House of Representatives to decide the outcome of the election. Clay’s political views were closer to those of John Quincy Adams than Andrew Jackson, and the speaker used his influence to elect Adams. President John Quincy Adams appointed Henry Clay as his secretary of State, a position he’d long desired. Jackson and his supporters called the move a “corrupt bargain.”

As secretary of State, Clay made trade agreements with newly independent Latin American countries. He sought to have the US involved in the Pan-American Congress of 1826, but Congress approved the measure too late. Adams was not reelected for a second term and Clay returned to his home in Kentucky until he was elected to the Senate in 1831. Two years later he worked on the Compromise Tariff of 1833, which lowered tariffs gradually. Between 1832 and 1848, Clay ran for president four more times, but never succeeded. After losing the Whig Party nomination in 1848, he hoped to retire to his Ashland estate. But the following year he was once again elected to the US Senate.

By this time, America had received new land following the Mexican-American War. The issue of slavery spreading to new territories was again a concern. In response, Clay introduced the Compromise of 1850, which was as controversial as the slavery debate itself. Clay’s bill proposed the organization of the Utah and New Mexico Territories, the admission of California as a free state, and prohibit slave auctions in the District of Columbia. Additionally, the bill would amend the Fugitive Slave Act. This ordered runaway slaves found anywhere in the United States be returned to their masters if a board of commissioners declared them fugitives. The bill would require authorities, including local officials in free states, to arrest Blacks and return them to slave territory. It also eliminated jury trials for those accused of being fugitive slaves and forbid them from testifying in their own defense. President Taylor opposed the compromise, wanting New Mexico to be admitted as a full state immediately, while Vice President Fillmore urged him to pass the bill.

Worn down by the constant fighting and weakened by tuberculosis, Clay left the capital and David Meriwether came in as his replacement. The compromise was ultimately passed after Taylor’s sudden death and Fillmore’s support.

Clay returned to Kentucky to live out his final years at Ashland. He succumbed to tuberculosis on June 29, 1852.

In later years, President Abraham Lincoln said Clay was “my ideal of a great man.” And in 1957, a Senate committee called Clay one of the five greatest US senators in American history.