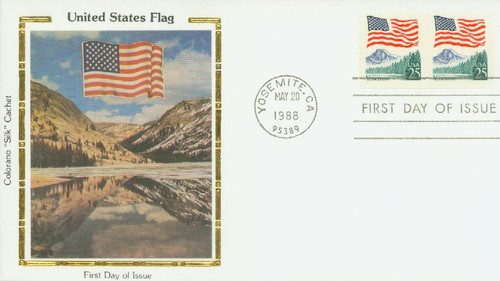

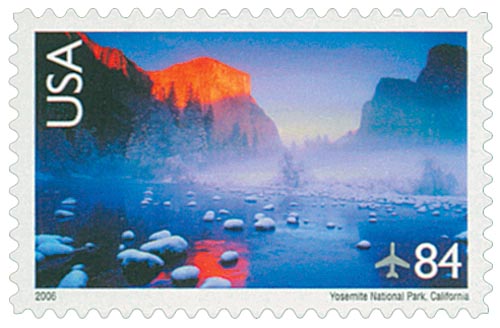

# 2280 FDC - 1988 25c Flag Over Yosemite, coil

Â

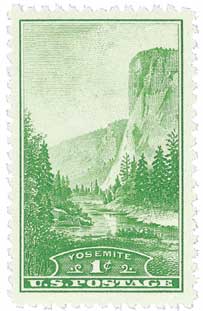

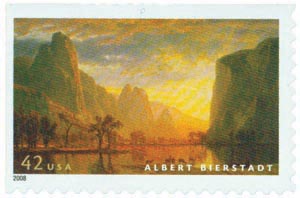

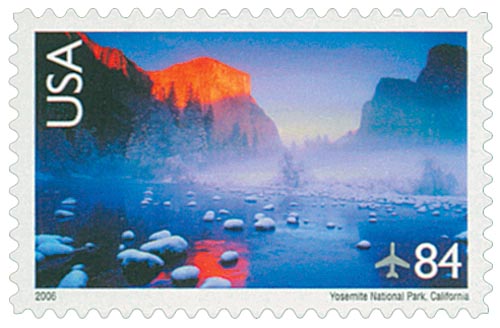

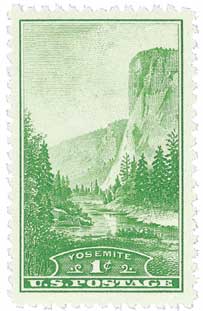

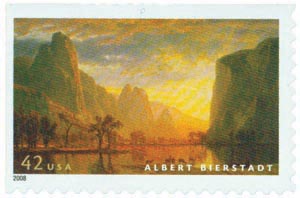

1987 25¢ Flag and Yosemite

City: Yosemite, CA

Quantity:Â 1,291,729,000

Printed By: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Engraved

Perforations: 10 vertically

Color: Multicolored

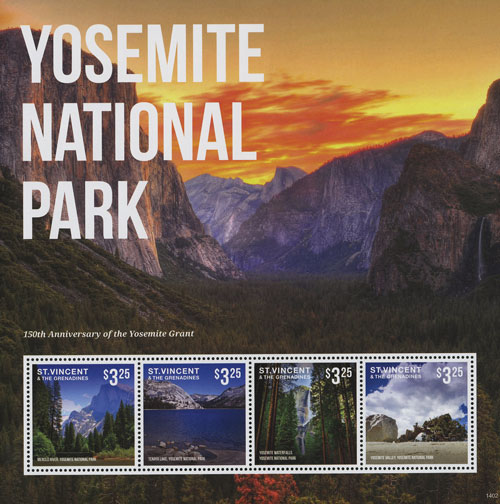

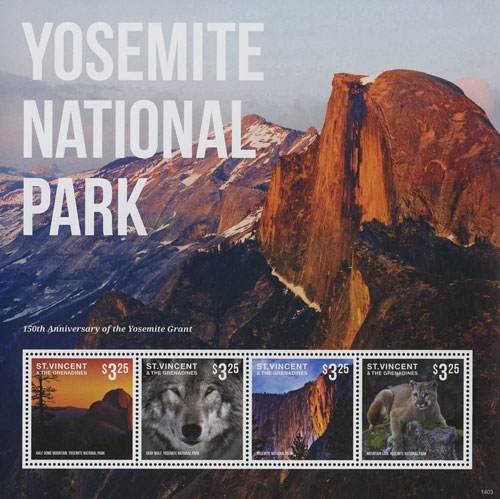

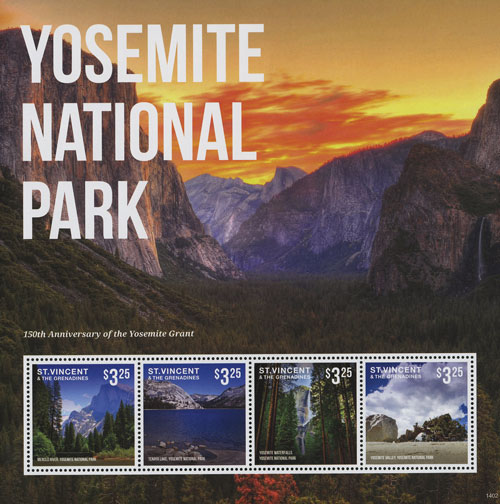

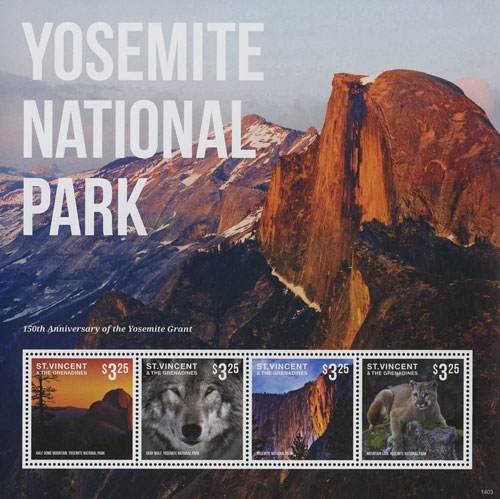

Yosemite Land GrantÂ

On June 30, 1864, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Yosemite Land Grant, which made Yosemite Valley the first piece of land set aside by the U.S. government for preservation and public use.

The first humans to visit the Yosemite area arrived about 10,000 years ago, and it was first settled around 3,000 years ago. By 1200 A.D., the area’s main inhabitants were the Sierra Miwoks, though other Miwok, Monos, and Shoshone tribes visited often to trade.

Among the early white visitors was Jim Savage, who ran a mining camp on the Merced River, about 10 miles west of the Yosemite Valley. In December 1850, Native Americans raided his camp and then retreated back to the mountains. Savage’s camp was one of several to be raided. The following year, the California governor organized the 200-man Mariposa Battalion to stop the raids. Jim Savage was placed in charge of the battalion and entered the west end of the Yosemite Valley while following a band of Ahwahneechee led by Chief Tenaya. Letters and articles written by members of the battalion during and after the battle helped bring attention to the little-known valley.

Eventually, the battalion captured Tenaya’s tribe, and they were escorted to a reservation. Accompanying the battalion was Doctor Lafayette Bunnell, who named several of Yosemite Valley’s features, including the valley itself. He chose to name the valley after a local tribe the Sierra Miwoks feared, the Yooh’meti. Bunnell and Savage pronounced it “Yosemite†and translated it as “full-grown grizzly bear.†Later, more accurate translations found it meant, “they are killers,†referring to the violent tribe who called themselves the Ahwahneechee.

In 1855, entrepreneur James Mason Hutchings and artist Thomas Ayres toured the area with two American Indian guides. Hutchings wanted to see the valley after hearing stories from the Mariposa Battalion about a waterfall “nearly a thousand feet tall.†Upon reaching Inspiration Point, Hutchings wrote in his journal, “We came upon a high point clear of trees from whence we had our first view of the singular and romantic valley; and as the scene opened in full view before us, we were almost speechless with wondering admiration at its wild and sublime grandeur.â€

Upon their return, Hutchings wrote several articles and books and Ayres’ sketches were the first accurate drawings of several park features. Hutchings returned to the valley several times, writing more articles and books and began publishing Hutchings’ Illustrated California Magazine, hoping to establish himself as the voice of the Yosemite Valley.

In the mid-1850s, Galen Clark became one of the first Americans to live in the valley.  He discovered the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoia in Wawona, an Indian camp in the Yosemite Valley, and spent the rest of his life trying to protect it. Although Clark was not the first to see the trees, he was likely the first to count and measure them.

Within his first few years in the valley, Clark built a log cabin, constructed roads, and put up a bridge over the Merced River for visitors entering Yosemite. At his cabin (known as Clark’s Station) he offered visitors shelter, meals, and a place to graze their horses.

Around 1860, Unitarian minister Thomas Starr King visited Yosemite and was amazed at the negative impact of settlement and commercial ventures on the land. He published several articles in the Boston Evening Transcript promoting the establishment of Yosemite as a National Park. He was likely the first person to spread this idea to a large audience. Oliver Wendell Holmes and John Greenleaf Whittier were among his supporters. Frederick Law Olmsted was so interested by his writing that he visited the valley in 1863 to see the damage for himself.

Others concerned about the valley’s safety included Galen Clark and Senator John Conness. The work of these men, plus Olmsted, photos from Carleton Watkins, and geologic reports from an 1863 survey forced legislators to take action. On June 30, 1864 President Abraham Lincoln signed a bill creating the Yosemite Grant. This was the first time a park had been set aside specifically for preservation and public use by the federal government. However, the Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoia Trees were made a California state park.

John Muir arrived in the Yosemite Valley in 1868 and was so taken with its natural beauty that he lived there for several years. Growing concerned over the area’s protection, he frequently invited people to camp there with him to share his ideas on preservation. One of these visitors was Robert Underwood Johnson, editor of The Century Magazine. Johnson gave Muir a national audience for his writing. Together, they lobbied Congress to establish Yosemite as a National Park. On October 1, 1890, their efforts paid off, and President Benjamin Harrison officially declared Yosemite a National Park. The Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove were added to the park in 1906.

Â

Â

1987 25¢ Flag and Yosemite

City: Yosemite, CA

Quantity:Â 1,291,729,000

Printed By: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Engraved

Perforations: 10 vertically

Color: Multicolored

Yosemite Land GrantÂ

On June 30, 1864, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Yosemite Land Grant, which made Yosemite Valley the first piece of land set aside by the U.S. government for preservation and public use.

The first humans to visit the Yosemite area arrived about 10,000 years ago, and it was first settled around 3,000 years ago. By 1200 A.D., the area’s main inhabitants were the Sierra Miwoks, though other Miwok, Monos, and Shoshone tribes visited often to trade.

Among the early white visitors was Jim Savage, who ran a mining camp on the Merced River, about 10 miles west of the Yosemite Valley. In December 1850, Native Americans raided his camp and then retreated back to the mountains. Savage’s camp was one of several to be raided. The following year, the California governor organized the 200-man Mariposa Battalion to stop the raids. Jim Savage was placed in charge of the battalion and entered the west end of the Yosemite Valley while following a band of Ahwahneechee led by Chief Tenaya. Letters and articles written by members of the battalion during and after the battle helped bring attention to the little-known valley.

Eventually, the battalion captured Tenaya’s tribe, and they were escorted to a reservation. Accompanying the battalion was Doctor Lafayette Bunnell, who named several of Yosemite Valley’s features, including the valley itself. He chose to name the valley after a local tribe the Sierra Miwoks feared, the Yooh’meti. Bunnell and Savage pronounced it “Yosemite†and translated it as “full-grown grizzly bear.†Later, more accurate translations found it meant, “they are killers,†referring to the violent tribe who called themselves the Ahwahneechee.

In 1855, entrepreneur James Mason Hutchings and artist Thomas Ayres toured the area with two American Indian guides. Hutchings wanted to see the valley after hearing stories from the Mariposa Battalion about a waterfall “nearly a thousand feet tall.†Upon reaching Inspiration Point, Hutchings wrote in his journal, “We came upon a high point clear of trees from whence we had our first view of the singular and romantic valley; and as the scene opened in full view before us, we were almost speechless with wondering admiration at its wild and sublime grandeur.â€

Upon their return, Hutchings wrote several articles and books and Ayres’ sketches were the first accurate drawings of several park features. Hutchings returned to the valley several times, writing more articles and books and began publishing Hutchings’ Illustrated California Magazine, hoping to establish himself as the voice of the Yosemite Valley.

In the mid-1850s, Galen Clark became one of the first Americans to live in the valley.  He discovered the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoia in Wawona, an Indian camp in the Yosemite Valley, and spent the rest of his life trying to protect it. Although Clark was not the first to see the trees, he was likely the first to count and measure them.

Within his first few years in the valley, Clark built a log cabin, constructed roads, and put up a bridge over the Merced River for visitors entering Yosemite. At his cabin (known as Clark’s Station) he offered visitors shelter, meals, and a place to graze their horses.

Around 1860, Unitarian minister Thomas Starr King visited Yosemite and was amazed at the negative impact of settlement and commercial ventures on the land. He published several articles in the Boston Evening Transcript promoting the establishment of Yosemite as a National Park. He was likely the first person to spread this idea to a large audience. Oliver Wendell Holmes and John Greenleaf Whittier were among his supporters. Frederick Law Olmsted was so interested by his writing that he visited the valley in 1863 to see the damage for himself.

Others concerned about the valley’s safety included Galen Clark and Senator John Conness. The work of these men, plus Olmsted, photos from Carleton Watkins, and geologic reports from an 1863 survey forced legislators to take action. On June 30, 1864 President Abraham Lincoln signed a bill creating the Yosemite Grant. This was the first time a park had been set aside specifically for preservation and public use by the federal government. However, the Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoia Trees were made a California state park.

John Muir arrived in the Yosemite Valley in 1868 and was so taken with its natural beauty that he lived there for several years. Growing concerned over the area’s protection, he frequently invited people to camp there with him to share his ideas on preservation. One of these visitors was Robert Underwood Johnson, editor of The Century Magazine. Johnson gave Muir a national audience for his writing. Together, they lobbied Congress to establish Yosemite as a National Park. On October 1, 1890, their efforts paid off, and President Benjamin Harrison officially declared Yosemite a National Park. The Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove were added to the park in 1906.

Â