# 291 - 1898 50c Trans-Mississippi Exposition: Western Mining Prospector

1898 50¢ Trans-Mississippi Exposition

First Day of Issue: June 17, 1898

Quantity issued: 530,400 (unknown quantity later destroyed)

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Method: Flat Plate

Watermark: Double-line watermark USPS

Perforation: 12

Color: Sage green

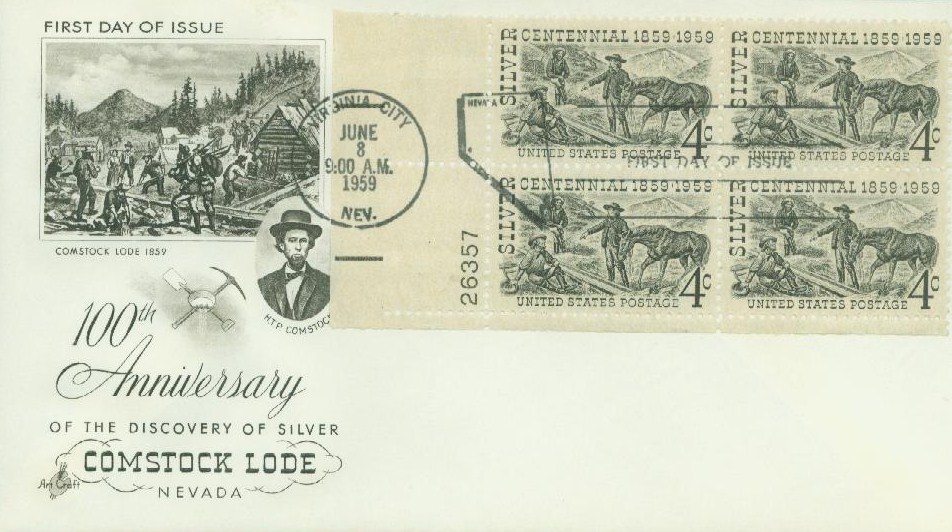

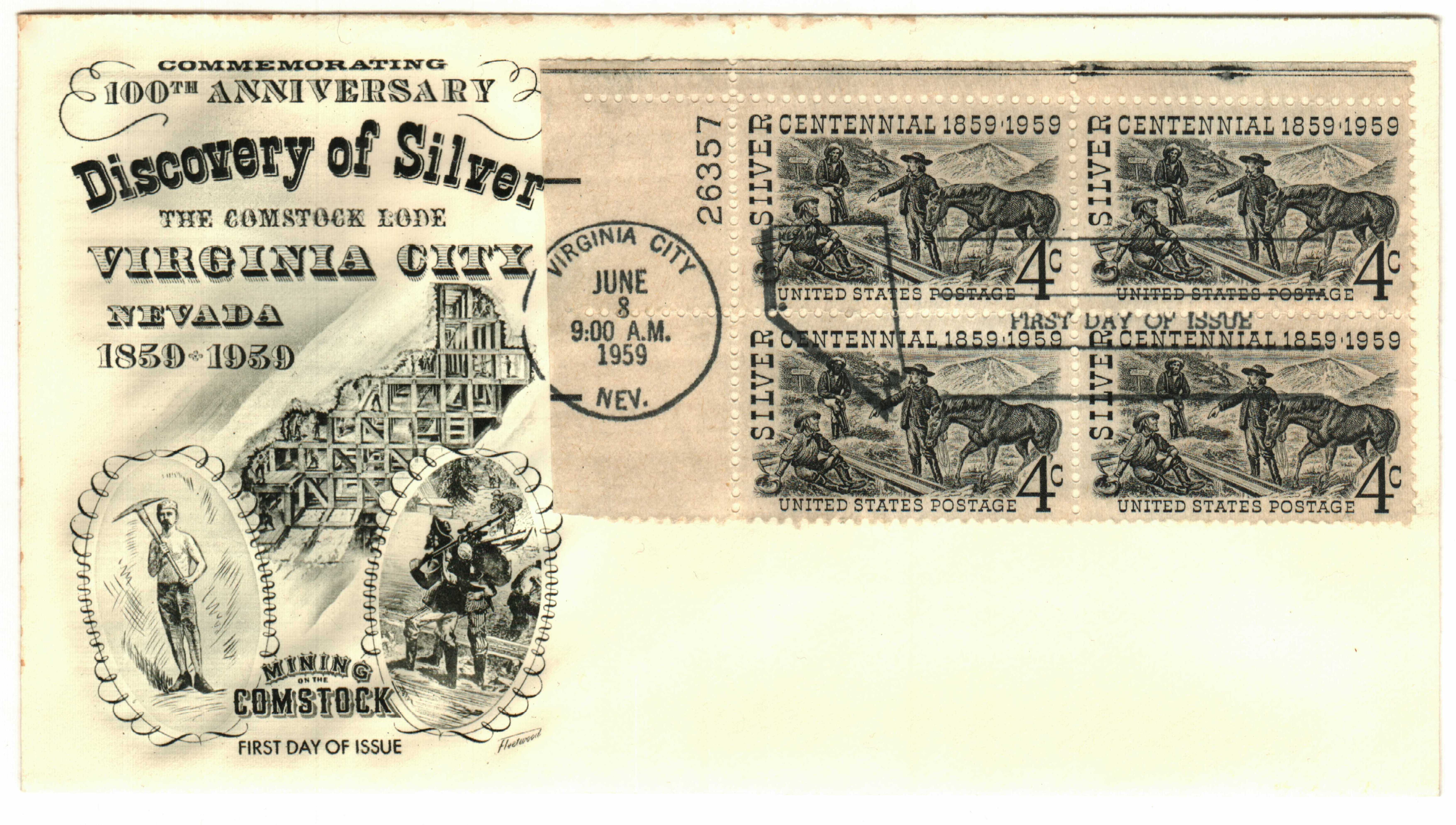

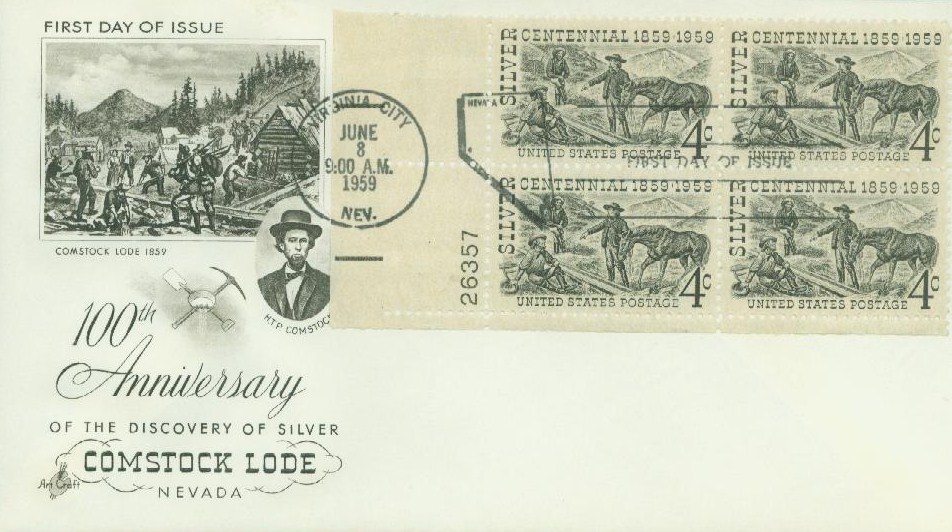

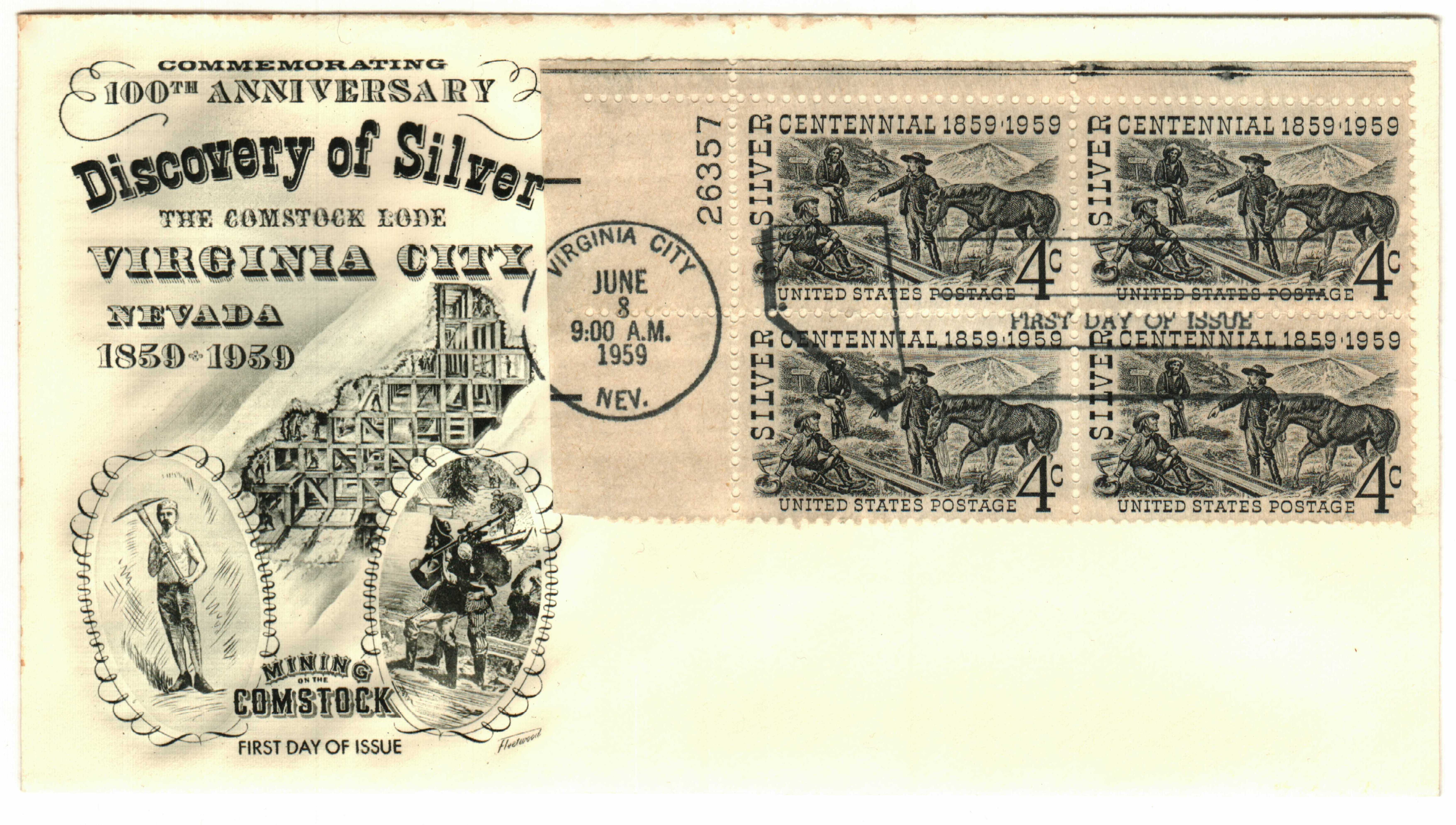

The Comstock Lode

Mormon immigrants first found gold in the area in the spring of 1850. They panned gold until the mountain snow melted and they could leave for California, where they expected to find more gold. In the years to come, more emigrants passed through the canyon and tried their luck, but when the water ran out near the end of summer, they would continue their trek to California.

Ethan and Hosea Grosh, veterans of the California Gold rush, are credited with discovering rich silver and gold veins in what is now called Gold Hill, near Virginia City in 1857. Hosea died of infection from a foot injury, and Ethan and an associate traveled to California with prospecting samples, hoping to raise funds for their dig. They left Henry Comstock to watch over their cabin and land. Ethan never finished the journey, dying of frostbite-related injuries. Comstock then claimed the cabin and land as his own.

In Comstock’s possession were more ore samples, as well as detailed notes that, being illiterate, he couldn’t read. The Grosh brothers had not yet filed a claim, so Comstock sought confirmation about the potential for gold and silver. When news of other miners finding silver ore came, he immediately started laying claim.

By the spring of 1859, most of the good ground had already been claimed. Peter O’Reilly and Patrick McLaughlin began prospecting with a rocker at the head of Six Mile Canyon. After finding nothing in the top dirt they were ready to quit, but when they sank a deeper pit to collect water, they found a hole with a “layer of rich black sand.” Meanwhile, Comstock soon learned of their efforts and convinced them to include him in their operation.

On June 12, 1859, O’Reilly and McLaughlin were digging in black manganese sand mixed with a bluish-gray material and gold. The bluish material was soft and putty like and clogged the rocker which made it hard to wash out the fine gold. On June 27, it was determined that they had found a rich sulfide of silver. The discovery came to be known as the “Comstock Lode” because it was land that Comstock had claimed as his own. It was the richest lode of silver found in the United States. News of the discovery spread fast, and soon miners from California and the Eastern US flocked to the area looking to strike it rich. Virginia City quickly became a thriving mining center.

The thick veins of silver were so soft they could sometimes be removed with just a shovel. Instead of the normally thin veins that were common in silver and gold ore, the Comstock Lode was sometimes hundreds of feet thick. Shafts were sunk to depths of up to 3,000 feet and cave-ins were common. Over the next two decades, nearly seven million tons of silver was mined.

The miners did not have an easy life. Provisions had to be shipped from California over the Sierra Nevada Mountains and were very expensive. Although some miners became millionaires, others found little or no wealth. Many of the miners were criminals, and lawlessness made the mining camps a dangerous place to live. Nevertheless, by 1860, Carson County’s mining camps held more than 6,700 people.

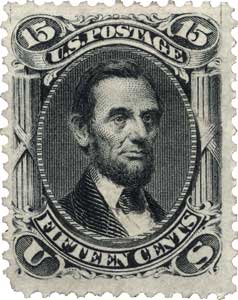

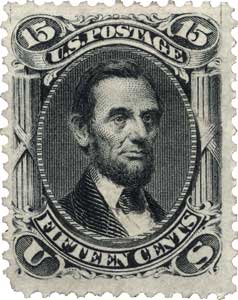

The gold and silver of the Comstock Lode were crucial to the Union’s financial wellbeing during the Civil War. In fact, Abraham Lincoln allowed Nevada to become a state, despite the fact that it did not have enough people to meet statehood requirements, to secure these riches for the North. The industry later made Nevada the second-largest silver-producing state in America, inspiring the nickname – the “Silver State.”

1898 50¢ Trans-Mississippi Exposition

First Day of Issue: June 17, 1898

Quantity issued: 530,400 (unknown quantity later destroyed)

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Method: Flat Plate

Watermark: Double-line watermark USPS

Perforation: 12

Color: Sage green

The Comstock Lode

Mormon immigrants first found gold in the area in the spring of 1850. They panned gold until the mountain snow melted and they could leave for California, where they expected to find more gold. In the years to come, more emigrants passed through the canyon and tried their luck, but when the water ran out near the end of summer, they would continue their trek to California.

Ethan and Hosea Grosh, veterans of the California Gold rush, are credited with discovering rich silver and gold veins in what is now called Gold Hill, near Virginia City in 1857. Hosea died of infection from a foot injury, and Ethan and an associate traveled to California with prospecting samples, hoping to raise funds for their dig. They left Henry Comstock to watch over their cabin and land. Ethan never finished the journey, dying of frostbite-related injuries. Comstock then claimed the cabin and land as his own.

In Comstock’s possession were more ore samples, as well as detailed notes that, being illiterate, he couldn’t read. The Grosh brothers had not yet filed a claim, so Comstock sought confirmation about the potential for gold and silver. When news of other miners finding silver ore came, he immediately started laying claim.

By the spring of 1859, most of the good ground had already been claimed. Peter O’Reilly and Patrick McLaughlin began prospecting with a rocker at the head of Six Mile Canyon. After finding nothing in the top dirt they were ready to quit, but when they sank a deeper pit to collect water, they found a hole with a “layer of rich black sand.” Meanwhile, Comstock soon learned of their efforts and convinced them to include him in their operation.

On June 12, 1859, O’Reilly and McLaughlin were digging in black manganese sand mixed with a bluish-gray material and gold. The bluish material was soft and putty like and clogged the rocker which made it hard to wash out the fine gold. On June 27, it was determined that they had found a rich sulfide of silver. The discovery came to be known as the “Comstock Lode” because it was land that Comstock had claimed as his own. It was the richest lode of silver found in the United States. News of the discovery spread fast, and soon miners from California and the Eastern US flocked to the area looking to strike it rich. Virginia City quickly became a thriving mining center.

The thick veins of silver were so soft they could sometimes be removed with just a shovel. Instead of the normally thin veins that were common in silver and gold ore, the Comstock Lode was sometimes hundreds of feet thick. Shafts were sunk to depths of up to 3,000 feet and cave-ins were common. Over the next two decades, nearly seven million tons of silver was mined.

The miners did not have an easy life. Provisions had to be shipped from California over the Sierra Nevada Mountains and were very expensive. Although some miners became millionaires, others found little or no wealth. Many of the miners were criminals, and lawlessness made the mining camps a dangerous place to live. Nevertheless, by 1860, Carson County’s mining camps held more than 6,700 people.

The gold and silver of the Comstock Lode were crucial to the Union’s financial wellbeing during the Civil War. In fact, Abraham Lincoln allowed Nevada to become a state, despite the fact that it did not have enough people to meet statehood requirements, to secure these riches for the North. The industry later made Nevada the second-largest silver-producing state in America, inspiring the nickname – the “Silver State.”