# 3142 - 1997 32c Classic American Aircraft

US #3142

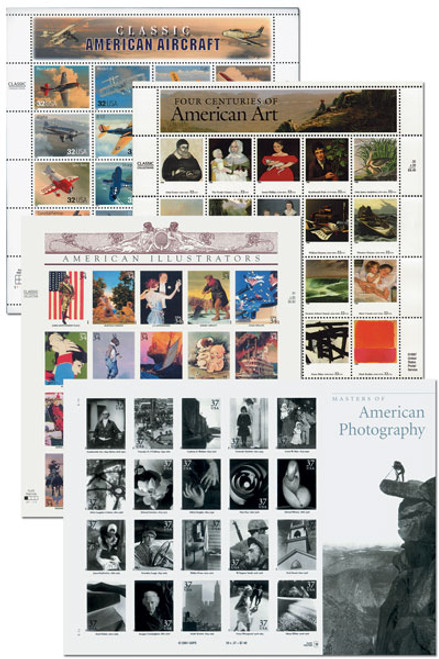

1997 Classic American Aircraft – Classic Collections Series

- 5th set in the Classic Collections stamp series

- Honors 20 different American aircraft on semi-jumbo stamps

- The back of each stamp includes information about the aircraft pictured in the design

Stamp Category: Commemorative

Series: Classic Collections

Value: 32¢, First Class Mail Rate

First Day of Issue: July 19, 1997

First Day City: Dayton, Ohio

Quantity Issued: 161,000,000

Printed by: Printed for Stamp Venturers at J.W. Fergusson and Sons, Richmond, Virginia

Printing Method: Photogravure

Format: Panes of 20 (Horizontal, 4 across, 5 down)

Perforations: 10.2 (APS Rotary Perforator)

Tagging: Large tagging block over all 20 stamps. The tagging block extends only to the outer edge of the vignette of the 16 stamps bordering the pane.

Why the stamps were issued: To celebrate some of the most iconic and important aircraft in American history.

About the stamp designs: The stamps picture artwork (oil paintings on Masonite) by William S. Phillips of Ashland, Oregon. The aircraft are shown at a variety of different angles and with no two backgrounds alike (lighting, clouds, and views of the ground all vary). This was done to prevent the stamps from looking too similar and stagnant. Phillips used many reference books, photographs, and even model planes he built himself and had his wife hold at different angles to ensure his paintings were as accurate as possible.

USPS special consultant Walter Boyne (retired US Ari Force colonel and first director of the National Air and Space Museum, founder of Air and Space magazine, and more) was chosen to develop a list of aircraft models to choose from. This is the list of criteria Boyne used to make his decisions:

“1) Importance to aviation history. Not all aircraft are equally important to aviation history, but all are of some enduring importance.

2) Contribution to technology. In a similar way, not all the selections contributed equally to technology, but most of them made significant contributions. In some cases, the contributions represented a first…. In other instances, the contribution was a combination of technological advances […] rather than a breakthrough in one particular area.

3) Public perception. In some instances, an aircraft, over time, by reasons of its performance, its appearance, or some other factor, would come to be recognized as the most memorable aircraft in its class.

4) Aesthetic appeal. Not all the aircraft selected could be called beautiful… Yet all have a tangible aesthetic appeal, and some are simply quite beautiful as sculptural art, at rest or in flight. A case could be made for some aircraft that they are so unaesthetic in appearance as to have a crude beauty…

5) A standard of excellence. Some of the aircraft were so dominant in their field that even if they lacked some of the above criteria – which they do not! – they would still have had to be selected.

6) A distinctive, evocative appearance. While this might be considered a subset of aesthetic appeal, it is different in that some aircraft simply call forth the era in which they appeared because of their distinctive appearance.

There are hundreds of other worthy contenders, and strong arguments might be made for them using the above criteria,” Boyne said, “But the selected aircraft have, on balance a unique combination of these qualities that make them truly, Classic American Aircraft.”

Special design details: Phillips’s airplane paintings (generally oil on Masonite) are highly detailed and have been featured in many art books and limited-edition prints. Phillips was also an Air Force veteran of the Vietnam War and traveled to the Persian Gulf as a Navy combat artist in 1988 to paint US aircraft and ships.

Art director Phil Jordan said “I wanted someone who flew, and Bill, like myself, is a recreational pilot… He has an ability to paint aircraft so they look as if they actually are in the air. They have a wonderful feeling to them. A lot of aviation artists are able to paint every rivet, every blade of grass, every desert grain of sand, but when you add it all up it’s very static and hard-edged. Bill’s work is very fluid and loose.”

First Day City: The stamps were dedicated at a ceremony at the US Air and Trade Show at Dayton International Airport. Dayton was home to the Wright brothers, the men who flew the first heavier-than-air craft in 1903.

About the Classic Collections Series: The Classic Collections series began in 1994 with the Legends of the West issue. The idea originated from Carl Burcham, manager of stamp and product marketing for USPS at the time. Each Classic Collections set consists of a pane of 20 different semi-jumbo stamps with descriptive selvage at the top (header) and informational text on the back of each stamp beneath the gum. The stamps are “broadly defined, Americana-themed subjects.”

The first four Classic Collections sets were accompanied by matching sets of picture postal cards showcasing the stamp designs. However, none were created for the Classic American Aircraft set.

History the stamp represents:

P-51 Mustang

Originally built for Britain’s Royal Air Force, the North American P-51 emerged at the end of World War II as the finest all-around piston-engine fighter in service. Affectionately referred to as the Mustang, its nickname was a suitable choice – referring not only to the plane’s American beginnings, but also its untamed power.

Although the basic design of the P-51 was sound, tests soon proved that the Mustang’s greatest disadvantage was its engine. In the RAF’s opinion, it was “a bloody good airplane” needing only “a bit more poke.” Engineers on both sides of the Atlantic contemplated the problem, and eventually it was suggested that a Rolls Royce merlin engine be installed – a modification which dramatically improved the P-51’s performance and revolutionized its potential.

Able to fly long range, the Mustang could now reach beyond Berlin, as far as Austria and Czechoslovakia. Known for accompanying the B-17s on their longest raids, the P-51 was also employed as a fighter, fighter-bomber, dive bomber, and reconnaissance aircraft. Following the war, it continued to be used by numerous foreign countries, including France, China, South Africa, Indonesia, Sweden, and Israel. After 40 years of service, the Mustang was finally retired in 1983.

Model B

Forever yearning to soar with the birds, man first became airborne in 1783. However, the fickle wind, not man, powered and controlled flight. Then, on December 17, 1903, the Wright brothers’ engine-driven, heavier-than-air Flyer lifted into the air and traveled 120 feet in 12 seconds. The Age of Flight had dawned.

By modern standards, the Flyer was not impressive. Its double-tiered wings and frame were made of balsa, plywood, and fabric, wired together for rigidity. A 12-horsewpoer petrol engine, strapped to the platform beneath the wings, catapulted the contraption down a wooden monorail to become airborne. The pilot lay beside the engine and held on. The craft was primitive and unstable. It had no seats, no wheels, and no flaps to control lateral movement. Nonetheless, an engine had powered it into the air.

Using a methodical scientific approach, the Wrights tackled these problems. Eventually, they were able to improve stability and control, add seats and wheels, and, most importantly, they could design more powerful engines. With each improvement, their aircraft set world speed, height, and distance records. In 1910, the potential of flight received official recognition when the US Army purchased two Model “Bs” for pilot training.

Cub

Highly sophisticated supersonic jets are so awe-inspiring, it’s easy to forget that the great majority of aircraft, at least in America, are small, simple machines.

William Thomas Piper was the first to manufacture airplanes for private use and is affectionately called “the Henry Ford of Aviation.” Since his small, economical two-seater Cub was introduced in 1929, many Americans have learned to fly. Today, more than a quarter of a million people own, and are licensed to fly, single- and twin-engine airplanes.

Although the low-wing Cherokee replaced the high-wing Cub in the 1960s, overall features remained the same. Both have a minimum number of parts to simplify production and reduce costs. Both are powered by simple piston engines, have fixed landing gears, unpressurized cabins, and relatively simple instruments. The Cherokee’s 1,200 parts are assembled in sections by three men with pneumatic hand tools. They can assemble the fuselage and cabin superstructure in four hours. With a few more hours, they can attach the wings and tail, install the engine, and wire the instrument panel.

Though “general aviation” aircraft are simple, they have all the system control features that larger aircraft do and can execute the full range of flying maneuvers.

Vega

For a few years after World War I, aircraft designers concentrated on developing military aircraft. After Congress withdrew funding, they turned their energies to designing aircraft for civilian use.

During the 1920s, aviation was the new frontier and each year, Americans and Europeans tested their ideas in national and international races. Seeing what worked, they went home and tried again.

Lockheed incorporated two German designs in its six-passenger Vega – Hugo Junkers’ cantilever wing and Rohrbach’s “stressed-skin” construction. Entering the 1928 National Air Races’ transcontinental derby, the Vega flew coast to coast in 24 hours and 9 minutes, winning hands down. The record was bettered again and again, making the Vega the finest transport monoplane of the time. In 1929, Amelia Earhart and her Vega competed in the first women’s transcontinental races, coming in third behind two other Vegas.

“Stressed-skin” construction is like a lobster claw in that the shell and wings bear the weight rather than an internal skeleton. This structure not only reduced drag and weight, it also increased cabin space by 35%. The Vega was so successful that it inspired worldwide development and influenced the design of larger transport aircraft.

Alpha

Despite its simple appearance, the Alpha fairly bristled with innovations in aircraft design and construction, setting a new pattern for transport planes. The first in a long line of “Northrop” high performance airplanes, the Alpha 2 was developed by John K. Northrop, a true pioneer and a self-made engineer.

Originally employed by Douglas Aircraft, Northrop later moved on to Lockheed where he designed the first of the Vega series. In 1928, he left Lockheed to form his own company. With his imagination fired by the semi-monocoque (single shell) construction theories of Adolf Rohrbach, Northrop made detailed studies of all-metal aircraft and experimented with the practical application of “stressed skin” covering. In 1930, he built America’s first metal plane of semimonocoque construction for the US Air Corps. The results were stunning.

Built for maximum performance, the Alpha was not only faster, but more economical as well. Powered with the Pratt & Whitney “Wasp” C engine, this sleek, low-winged monoplane could carry up to six passengers and had removable seating for hauling large loads of mail and cargo. In fact, the Alpha 2 and Alpha 3 that followed were so successful that other companies quickly turned to building only all-metal monoplanes.

B-10

The Martin Company is an old-timer in the relatively young aviation industry. As early as 1909, the company produced military bombers for the US Army. And its MB twin-engine bomber of 1918, the first American bomber to sink a battleship, became a standard post-war type for several years. The company was even manufacturing all-metal airplanes for the Navy as early as 1922.

In 1932, the company produced a twin-engine, mid-wing monoplane bomber. Two years later, it began testing the use of Wright Cyclone engines and Pratt & Whitney Hornet engines. In 1935, the company finally came up with a winner – the B-10 (“B” designating bomber).

The B-10 was fitted with 740-horsepower Cyclone engines, Sperry automatic pilot, wing flaps, constant-speed propellers, and de-icers, as well as continuous cockpit enclosures. After adding a Browning machine gun in the nose turret and two in the rear cockpit, top and bottom, it was ready for wartime service.

The B-10 revolutionized bomber design both here and abroad. Its new features allowed pilots to hear more, see more, and do more. Best yet, its powerful engines allowed it to outfly the fastest US fighters by 100 miles per hour – an important lifesaving feature.

Corsair

Initially dubbed a failure, the Vought Corsair eventually proved its superiority over the Grumman Wildcat, becoming the most important naval attack fighter of World War II. In fact, by 1943, all Pacific-based Marine fighter squadrons had been re-equipped with the Corsair. And as testament to its outstanding service, this fighter remained in production for 13 years.

Conceived in 1938, the Corsair’s design started with the basic idea of marrying the most powerful engine available – the new 2000-hp Pratt & Whitney Double Wasp – with the smallest compatible airframe. The use of this engine, whose greater power necessitated the largest propeller of any contemporary fighter, resulted in adopting an inverted gull wing. This unique feature kept the main landing gear legs reasonably short, while allowing adequate ground clearance for the air crew.

Early trial flights not only revealed a number of problems, but also promised great potential. At 404 mph, the Corsair was the first US fighter to exceed 400 mph. With its distinctive engine note and high “kill ratio” it soon earned the nickname “Whistling Death” from its Japanese opponents. In the Pacific Theater alone, the Corsair shot down 2,140 enemy aircraft with only 189 losses, earning a reputation as the very best of its kind.

Stratojet

Introduced in 1939, the first jet-powered airplane revolutionized the aviation industry. Significantly eliminating the limitations imposed by the propeller, the jet engine paved the way for increases in aircraft speed, size, and operating altitudes. But with the outbreak of World War II, further development of this new technology came to a halt as resources were poured into producing military aircraft.

Not surprisingly though, countries on both sides of the war were eager to take advantage of the jet engine. And finally, in 1943, Boeing, in response to US Army Air Force interest in a turbojet-powered bomber, began preliminary studies into creating such as aircraft. The result was Model 450, better known as the Stratojet.

Incredible for its time, the B-47 Stratojet featured six engines, sweptback wings, a bombardier’s station in the nose, remote-controlled tail armament, and two groups of nine Aerojet JATO rocket units to provide extra thrust for takeoff. Making its first flight on December 17, 1947, this high-performance bomber entered service in the early 1950s, equipping a large part of the USAF’s Strategic Air Command. Modified for Tactical Air Command and later for weather reconnaissance, the last B-47s in service were retired in 1969.

Gee Bee

Introduced in 1939, the first jet-powered airplane revolutionized the aviation industry. Significantly eliminating the limitations imposed by the propeller, the jet engine paved the way for increases in aircraft speed, size, and operating altitudes. But with the outbreak of World War II, further development of this new technology came to a halt as resources were poured into producing military aircraft.

Not surprisingly though, countries on both sides of the war were eager to take advantage of the jet engine. And finally, in 1943, Boeing, in response to US Army Air Force interest in a turbojet-powered bomber, began preliminary studies into creating such as aircraft. The result was Model 450, better known as the Stratojet.

Incredible for its time, the B-47 Stratojet featured six engines, sweptback wings, a bombardier’s station in the nose, remote-controlled tail armament, and two groups of nine Aerojet JATO rocket units to provide extra thrust for takeoff. Making its first flight on December 17, 1947, this high-performance bomber entered service in the early 1950s, equipping a large part of the USAF’s Strategic Air Command. Modified for Tactical Air Command and later for weather reconnaissance, the last B-47s in service were retired in 1969.

Staggerwing

Beech Aircraft Corporation was established in 1932. The first airplane it produced was a four-passenger Model 17 biplane. Unlike former biplanes, its wings were staggered; that is, its upper wing lay slightly behind the bottom wing, and it proved to be a fine flyer.

America was in the depths of the Depression at the very time when aircraft and engine designers were producing a profusion of technological ideas. Because it was costly to translate those ideas into reality, established businesses, especially oil companies, sponsored the fledgling aviation industry. Thus it was that the Ethyl Corporation bought Beech’s Model 17, and in 1933 entered it in the Texaco Trophy races in Florida. Not surprisingly, it won.

Meanwhile, Beech engineers continued their refinements. In 1937, they put aileron-type full-length flaps on the lower wings, and ailerons on the upper wings. These increased the aircraft’s controllability and maneuverability enormously, establishing the norm for all future airplanes. Famous aviator Jacqueline Cochran, seen on US #3066, owned a Model D-17W.

During World War II, several versions of the Staggerwing were used as utility transports and communications aircraft by the Army and Navy.

Flying Fortress

On July 28, 1935, Boeing’s Model 299, as it was called at the time, embarked on its first flight from a Seattle airfield. The plane would go on to become one of the most famous used during World War II.

As Seattle Times reporter Richard Smith watched the four-engine plane packed with machine gun mounts pass by, he called it a “Flying Fortress.” Boeing liked the name and trademarked it, designated the plane the B-17 Flying Fortress.

The B-17 was Boeing’s first plane to have a flight deck instead of an open cockpit and it was heavily armed with bombs and five .30-caliber machine guns. It was introduced into battle in 1941 by the British, and as the US joined the war, many more were needed. Over 12,000 were produced for the war. The Japanese called them “four-engine fighters” because they could sustain significant damage but remain in the air. According to General Carl Spaatz, “Without the B-17 we may have lost the war.”

Stearman

Most American and Canadian pilots who served in World War I learned to fly in a Curtiss Jenny. Three decades later, the Stearman Kaydet served the same role during World War II. Its military designation was preceeded by a PT, the “P” indicating a pursuit or fighter plane, the “T” indicating that it was a trainer.

The Stearman Kaydet was developed as a two-seat biplane trainer in 1934 by the Stearman Aircraft Company of Wichita, Kansas. Later that year, Boeing purchased the company and entered the Kaydet into the Army Primary Trainer Competition. The Kaydet won and the Army put in an order for several. When war threatened a few years later, the Army purchased additional planes. By the time Boeing stopped production in 1945, it had turned out over 10,000 Kaydets.

The Stearman Kaydet was a throwback to an earlier age of baling wire and fabric biplanes. An excellent introduction to handling large aircraft, the Kaydet was a sturdy plane, withstanding the many mishaps of inexperienced pilots. However, its size and high center of gravity made it prone to ground looping, a flight characteristic difficult to handle. Consequently, the Kaydet was nicknamed the “Washing Machine” because of the number of would-be pilots that got “washed out” of flight training.

Constellation

The original Constellation was developed in 1939 as a commercial airliner for Transcontinental & Western Air – later Trans-World Airlines (TWA). Designed to be the “fastest, high performance airplane in the world,” its specifications called for a 3,000-mile range and a maximum 18,000-pound payload capacity.

The outbreak of World War II, however, caused the plane to be modified as the C-69 military transport – the first example of which was flown on January 9, 1943. As war demands increased, the plants were commandeered (seized for military use) as they came off the production line. But despite new features, which included hydraulically powered controls and a thermal de-icing system for wing- and tail-unit leading edges, it wasn’t until after the war that the Constellation made its impact on air transportation.

TWA flew its first Constellation on October 1, 1945. The following year, Pan-Am Airways introduced the “Connie,” as it affectionately became known, on the company’s New York-Bermuda route. Extremely efficient with its streamlined fuselage and triple fins and rudders, the Constellation also offered the advantages of a pressurized cabin and more adequate range for transatlantic operation. Before long, it was operating in worldwide services.

Lightning

When the US Army Air Corps issued specifications for a high-altitude interceptor in 1937, Lockheed was already aware of the qualities demanded: speed, ceiling, and firepower combined with the ability to carry enough fuel for superior range were essential. Built to meet these requirements, Lockheed’s P-38 Lightning became one of the most feared and respected aircraft to fly in the Axis skies. Its firepower was lethal and its long range allowed it to accompany bombers to Berlin and beyond.

The Lightning entered service in 1941 and was deployed in Europe, North Africa, and the Pacific during 1942. Throughout the war it gained steadily in performance, demonstrating remarkable versatility. Although it achieved its ultimate effectiveness as an escort, the P-38 was also used extensively as a ground-attack aircraft, as well as during night raids, photograph reconnaissance missions, and to drop smokescreen layers.

It was this combination of power and versatility that gained the P-38 a formidable reputation among the Japanese and Germans, who dubbed it the “fork-tailed devil.” In fact, the Lightning ended the war with more Japanese aircraft to its credit than any other type. And it was the only American fighter built before WWII to still be in production on VJ Day.

Peashooter

In the 21 years between the two World Wars, aviation technology progressed at a remarkable pace. By the 1930s, the biplane had become obsolete, replaced by the speedy new monoplane. Utilizing improved concepts of fighter design, the monoplane achieved a new level of high performance.

This change – from biplane to the monoplane – was marked in 1934 by the entry into service of the Boeing P-26. Nicknamed the “Peashooter,” because of its bulbous lines and its stubby radial engine, the P-26 was the result of close collaboration between Boeing and the US Army. The prototype made its first flight in 1932, and although the P-26 retained an open cockpit, wire-braced wings, and a fixed undercarriage, it was a major step forward in airplane construction. For it was the first plane to feature an all-metal construction, as well as monoplane wings.

With modifications and larger engines, the Peashooter went into service at the beginning of 1934, making the US Air Corps one of the first air forces to use monoplane fighters. For almost five years it represented the front-line equipment of fighter units. And when World War II erupted, about a dozen P-26s were thrown into battle. One of them brought down one of the first Japanese aircraft of the war.

Tri-Motor

In the 21 years between World War I and II, airplane technology changed drastically. Larger, more powerful airplanes required stronger frames and wings. This led to one of the most significant advance – the switch to metal structures.

Throughout the 1920s, most manufacturers used both metal and spruce wood and continued to dress their aircraft in an outer skin of fabric. The first American company to build an all-metal airplane was the Stout Metal Airplane Company, which became a division of Ford Motor Company in 1925. The following year, the company produced a three-engined commercial monoplane powered by 200-horsepower Wright Whirlwind engines. With the installation of newer 300-hp Wright engines later that year, the 11-passenger 4-AT, or Ford Tri-Motor, was born.

Though ahead of its time, the “Tin Goose,” as it was called, was noisy, uncomfortable, and cold – passengers even had to endure being sprayed by mud when the plane landed. Nonetheless, with a maximum take-off weight of 10,130 pounds, a cruising speed of 107 mph, and a range of 570 miles, it was the best there was. In all, 200 Tri-Motors were built from 1926 to 1933. At the peak of production in 1929, the company turned out four planes a week, producing a total of 78 airplanes that year alone.

DC-3

When the first DC-3 rolled down the runway in 1934, few knew it was destined to become the most famous commercial airplane ever built. Though not the first low-wing monoplane in a world still dominated by biplanes, it was immediately popular with airlines in America and Europe. It was easy to fly and had the passenger comforts so lacking in the Tri-Motor.

With the outbreak of World War II, the Douglas Aircraft Corporation went into immediate mass-production. Altogether, 10,000 DC-3s ferried thousands of US and British servicemen as C-47 Skytrains, and Dakotas respectively. Converted to civilian use after the war, the DC-3 became the world’s principal airliner and biggest moneymaker in its class. As late as 1965, DC-3s still outnumbered all other types of airliners.

More than anything else, the DC-3 was an indestructible workhorse because it was a stress-skinned “fail-safe” airplane. Prior to DC-3s, airplanes had a lifespan of about 6,000 hours and had a tendency to come apart at the seams when a structural member broke. When a wing spar in the DC-3 broke, the weight was picked up by alternate spars. This type of construction eliminated catastrophic chain reactions and reduced fatigue, which, in turn, enormously increased its safety and its lifespan.

Clipper

In most mind, Pan American Airlines and “Clipper” are synonymous. Though not the first American international airline, Pan Am was perhaps the most successful, and was certainly a leader in the industry.

The company got its start in 1927, flying mail between Key West, Florida, and Havana, Cuba. Scheduled passenger service followed the next year. And by 1929, with Charles Lindbergh’s help, it had mapped out a 12,000-mile route between North, South, and Central America.

By 1936, Pan Am was ready to develop its transoceanic service. Boeing was recruited to build a comfortable 74-passenger airplane with a range of 3,500 miles – a monumental request. Although Boeing considered declining the offer, instead it took the XB-15 high-wing – predecessor of the Flying Fortress – and added a luxurious double-decker hull. In order to lift the craft, crew, and payload, it installed four of the most powerful engines available – Wright Twin Cyclone 14-cylinder engines.

The six glamorous 314 Clippers that began service in 1939 flew only a few short years, but garnered many firsts. Not only did they fly the first transpacific flight in 1936, but also the first transatlantic flight in 1939, and the first round-the-world flight in 1947.

Jenny

Bicycle manufacturer Glenn Curtiss began his career in aviation design developing seaplanes. In 1915, he was awarded the first contract to build US Navy planes. Believig in the future of flight, he sought to design an airplane which could be mass-produced. The result was his eight-cylinder OX-5 engine combined with features from a British aircraft designer. Designated the JN-4, it became affectionately known as the “Jenny.”

Created at the onset of World War I, the Jenny played a major role in the fighting – the only American mass-produced aircraft to do so. During the war years, Curtiss manufactured more than 6,400 units for the US Army Air Corps and US Navy (at $5,000 each) as well as over 2,000 units for other Allied governments, including Great Britain and Russia.

Because of the quantities produced, 95% of all American and Canadian WWI pilots earned their wings in a Jenny. Hundreds were sold as surplus after the Armistice. Barnstormers quickly traveled the country performing daring feats, thereby introducing ordinary Americans to the thrills of aviation. Many more became familiar with aviation when the US Post Office issued the 24¢ Jenny stamp to inaugurate the world’s first regularly scheduled transportation of mail by air.

Wildcat

The Grumman Aerospace Corporation was founded by Leroy Grumman, a US industrialist and master designer of US fighter planes. During the 1930s Grumman’s inventions – retractable landing gear and a folding wing later used on the Wildcat carrier fighter – earned him countless US Navy contracts. In 1938, negotiations between the Navy and Grumman led to the development for the XF4F-3 (“X” designating “experimental”). Officially dubbed the “Wildcat,” it became the first of the famous Grumman “cat” family.

By December 1941, 245 Wildcats had entered US service, and for the next two years they served as the main US Navy and Marine Corps fighter. In addition to an increased wingspan, the F4F also sported “squared” wing and tail tips. Necessary for additional lifting surface required by heavier aircraft, this feature eventually became a “trademark” of the Grumman aircraft.

Although not particularly outstanding in terms of performance, the Wildcat was staunchly rugged and well-armed. And in the hands of an experienced pilot, it proved the equal of the highly effective Japanese Zero. Able to compile a distinguished combat record, Grumman aircraft reportedly shot down more than 60% of enemy aircraft in the Pacific Theater during World War II.

US #3142

1997 Classic American Aircraft – Classic Collections Series

- 5th set in the Classic Collections stamp series

- Honors 20 different American aircraft on semi-jumbo stamps

- The back of each stamp includes information about the aircraft pictured in the design

Stamp Category: Commemorative

Series: Classic Collections

Value: 32¢, First Class Mail Rate

First Day of Issue: July 19, 1997

First Day City: Dayton, Ohio

Quantity Issued: 161,000,000

Printed by: Printed for Stamp Venturers at J.W. Fergusson and Sons, Richmond, Virginia

Printing Method: Photogravure

Format: Panes of 20 (Horizontal, 4 across, 5 down)

Perforations: 10.2 (APS Rotary Perforator)

Tagging: Large tagging block over all 20 stamps. The tagging block extends only to the outer edge of the vignette of the 16 stamps bordering the pane.

Why the stamps were issued: To celebrate some of the most iconic and important aircraft in American history.

About the stamp designs: The stamps picture artwork (oil paintings on Masonite) by William S. Phillips of Ashland, Oregon. The aircraft are shown at a variety of different angles and with no two backgrounds alike (lighting, clouds, and views of the ground all vary). This was done to prevent the stamps from looking too similar and stagnant. Phillips used many reference books, photographs, and even model planes he built himself and had his wife hold at different angles to ensure his paintings were as accurate as possible.

USPS special consultant Walter Boyne (retired US Ari Force colonel and first director of the National Air and Space Museum, founder of Air and Space magazine, and more) was chosen to develop a list of aircraft models to choose from. This is the list of criteria Boyne used to make his decisions:

“1) Importance to aviation history. Not all aircraft are equally important to aviation history, but all are of some enduring importance.

2) Contribution to technology. In a similar way, not all the selections contributed equally to technology, but most of them made significant contributions. In some cases, the contributions represented a first…. In other instances, the contribution was a combination of technological advances […] rather than a breakthrough in one particular area.

3) Public perception. In some instances, an aircraft, over time, by reasons of its performance, its appearance, or some other factor, would come to be recognized as the most memorable aircraft in its class.

4) Aesthetic appeal. Not all the aircraft selected could be called beautiful… Yet all have a tangible aesthetic appeal, and some are simply quite beautiful as sculptural art, at rest or in flight. A case could be made for some aircraft that they are so unaesthetic in appearance as to have a crude beauty…

5) A standard of excellence. Some of the aircraft were so dominant in their field that even if they lacked some of the above criteria – which they do not! – they would still have had to be selected.

6) A distinctive, evocative appearance. While this might be considered a subset of aesthetic appeal, it is different in that some aircraft simply call forth the era in which they appeared because of their distinctive appearance.

There are hundreds of other worthy contenders, and strong arguments might be made for them using the above criteria,” Boyne said, “But the selected aircraft have, on balance a unique combination of these qualities that make them truly, Classic American Aircraft.”

Special design details: Phillips’s airplane paintings (generally oil on Masonite) are highly detailed and have been featured in many art books and limited-edition prints. Phillips was also an Air Force veteran of the Vietnam War and traveled to the Persian Gulf as a Navy combat artist in 1988 to paint US aircraft and ships.

Art director Phil Jordan said “I wanted someone who flew, and Bill, like myself, is a recreational pilot… He has an ability to paint aircraft so they look as if they actually are in the air. They have a wonderful feeling to them. A lot of aviation artists are able to paint every rivet, every blade of grass, every desert grain of sand, but when you add it all up it’s very static and hard-edged. Bill’s work is very fluid and loose.”

First Day City: The stamps were dedicated at a ceremony at the US Air and Trade Show at Dayton International Airport. Dayton was home to the Wright brothers, the men who flew the first heavier-than-air craft in 1903.

About the Classic Collections Series: The Classic Collections series began in 1994 with the Legends of the West issue. The idea originated from Carl Burcham, manager of stamp and product marketing for USPS at the time. Each Classic Collections set consists of a pane of 20 different semi-jumbo stamps with descriptive selvage at the top (header) and informational text on the back of each stamp beneath the gum. The stamps are “broadly defined, Americana-themed subjects.”

The first four Classic Collections sets were accompanied by matching sets of picture postal cards showcasing the stamp designs. However, none were created for the Classic American Aircraft set.

History the stamp represents:

P-51 Mustang

Originally built for Britain’s Royal Air Force, the North American P-51 emerged at the end of World War II as the finest all-around piston-engine fighter in service. Affectionately referred to as the Mustang, its nickname was a suitable choice – referring not only to the plane’s American beginnings, but also its untamed power.

Although the basic design of the P-51 was sound, tests soon proved that the Mustang’s greatest disadvantage was its engine. In the RAF’s opinion, it was “a bloody good airplane” needing only “a bit more poke.” Engineers on both sides of the Atlantic contemplated the problem, and eventually it was suggested that a Rolls Royce merlin engine be installed – a modification which dramatically improved the P-51’s performance and revolutionized its potential.

Able to fly long range, the Mustang could now reach beyond Berlin, as far as Austria and Czechoslovakia. Known for accompanying the B-17s on their longest raids, the P-51 was also employed as a fighter, fighter-bomber, dive bomber, and reconnaissance aircraft. Following the war, it continued to be used by numerous foreign countries, including France, China, South Africa, Indonesia, Sweden, and Israel. After 40 years of service, the Mustang was finally retired in 1983.

Model B

Forever yearning to soar with the birds, man first became airborne in 1783. However, the fickle wind, not man, powered and controlled flight. Then, on December 17, 1903, the Wright brothers’ engine-driven, heavier-than-air Flyer lifted into the air and traveled 120 feet in 12 seconds. The Age of Flight had dawned.

By modern standards, the Flyer was not impressive. Its double-tiered wings and frame were made of balsa, plywood, and fabric, wired together for rigidity. A 12-horsewpoer petrol engine, strapped to the platform beneath the wings, catapulted the contraption down a wooden monorail to become airborne. The pilot lay beside the engine and held on. The craft was primitive and unstable. It had no seats, no wheels, and no flaps to control lateral movement. Nonetheless, an engine had powered it into the air.

Using a methodical scientific approach, the Wrights tackled these problems. Eventually, they were able to improve stability and control, add seats and wheels, and, most importantly, they could design more powerful engines. With each improvement, their aircraft set world speed, height, and distance records. In 1910, the potential of flight received official recognition when the US Army purchased two Model “Bs” for pilot training.

Cub

Highly sophisticated supersonic jets are so awe-inspiring, it’s easy to forget that the great majority of aircraft, at least in America, are small, simple machines.

William Thomas Piper was the first to manufacture airplanes for private use and is affectionately called “the Henry Ford of Aviation.” Since his small, economical two-seater Cub was introduced in 1929, many Americans have learned to fly. Today, more than a quarter of a million people own, and are licensed to fly, single- and twin-engine airplanes.

Although the low-wing Cherokee replaced the high-wing Cub in the 1960s, overall features remained the same. Both have a minimum number of parts to simplify production and reduce costs. Both are powered by simple piston engines, have fixed landing gears, unpressurized cabins, and relatively simple instruments. The Cherokee’s 1,200 parts are assembled in sections by three men with pneumatic hand tools. They can assemble the fuselage and cabin superstructure in four hours. With a few more hours, they can attach the wings and tail, install the engine, and wire the instrument panel.

Though “general aviation” aircraft are simple, they have all the system control features that larger aircraft do and can execute the full range of flying maneuvers.

Vega

For a few years after World War I, aircraft designers concentrated on developing military aircraft. After Congress withdrew funding, they turned their energies to designing aircraft for civilian use.

During the 1920s, aviation was the new frontier and each year, Americans and Europeans tested their ideas in national and international races. Seeing what worked, they went home and tried again.

Lockheed incorporated two German designs in its six-passenger Vega – Hugo Junkers’ cantilever wing and Rohrbach’s “stressed-skin” construction. Entering the 1928 National Air Races’ transcontinental derby, the Vega flew coast to coast in 24 hours and 9 minutes, winning hands down. The record was bettered again and again, making the Vega the finest transport monoplane of the time. In 1929, Amelia Earhart and her Vega competed in the first women’s transcontinental races, coming in third behind two other Vegas.

“Stressed-skin” construction is like a lobster claw in that the shell and wings bear the weight rather than an internal skeleton. This structure not only reduced drag and weight, it also increased cabin space by 35%. The Vega was so successful that it inspired worldwide development and influenced the design of larger transport aircraft.

Alpha

Despite its simple appearance, the Alpha fairly bristled with innovations in aircraft design and construction, setting a new pattern for transport planes. The first in a long line of “Northrop” high performance airplanes, the Alpha 2 was developed by John K. Northrop, a true pioneer and a self-made engineer.

Originally employed by Douglas Aircraft, Northrop later moved on to Lockheed where he designed the first of the Vega series. In 1928, he left Lockheed to form his own company. With his imagination fired by the semi-monocoque (single shell) construction theories of Adolf Rohrbach, Northrop made detailed studies of all-metal aircraft and experimented with the practical application of “stressed skin” covering. In 1930, he built America’s first metal plane of semimonocoque construction for the US Air Corps. The results were stunning.

Built for maximum performance, the Alpha was not only faster, but more economical as well. Powered with the Pratt & Whitney “Wasp” C engine, this sleek, low-winged monoplane could carry up to six passengers and had removable seating for hauling large loads of mail and cargo. In fact, the Alpha 2 and Alpha 3 that followed were so successful that other companies quickly turned to building only all-metal monoplanes.

B-10

The Martin Company is an old-timer in the relatively young aviation industry. As early as 1909, the company produced military bombers for the US Army. And its MB twin-engine bomber of 1918, the first American bomber to sink a battleship, became a standard post-war type for several years. The company was even manufacturing all-metal airplanes for the Navy as early as 1922.

In 1932, the company produced a twin-engine, mid-wing monoplane bomber. Two years later, it began testing the use of Wright Cyclone engines and Pratt & Whitney Hornet engines. In 1935, the company finally came up with a winner – the B-10 (“B” designating bomber).

The B-10 was fitted with 740-horsepower Cyclone engines, Sperry automatic pilot, wing flaps, constant-speed propellers, and de-icers, as well as continuous cockpit enclosures. After adding a Browning machine gun in the nose turret and two in the rear cockpit, top and bottom, it was ready for wartime service.

The B-10 revolutionized bomber design both here and abroad. Its new features allowed pilots to hear more, see more, and do more. Best yet, its powerful engines allowed it to outfly the fastest US fighters by 100 miles per hour – an important lifesaving feature.

Corsair

Initially dubbed a failure, the Vought Corsair eventually proved its superiority over the Grumman Wildcat, becoming the most important naval attack fighter of World War II. In fact, by 1943, all Pacific-based Marine fighter squadrons had been re-equipped with the Corsair. And as testament to its outstanding service, this fighter remained in production for 13 years.

Conceived in 1938, the Corsair’s design started with the basic idea of marrying the most powerful engine available – the new 2000-hp Pratt & Whitney Double Wasp – with the smallest compatible airframe. The use of this engine, whose greater power necessitated the largest propeller of any contemporary fighter, resulted in adopting an inverted gull wing. This unique feature kept the main landing gear legs reasonably short, while allowing adequate ground clearance for the air crew.

Early trial flights not only revealed a number of problems, but also promised great potential. At 404 mph, the Corsair was the first US fighter to exceed 400 mph. With its distinctive engine note and high “kill ratio” it soon earned the nickname “Whistling Death” from its Japanese opponents. In the Pacific Theater alone, the Corsair shot down 2,140 enemy aircraft with only 189 losses, earning a reputation as the very best of its kind.

Stratojet

Introduced in 1939, the first jet-powered airplane revolutionized the aviation industry. Significantly eliminating the limitations imposed by the propeller, the jet engine paved the way for increases in aircraft speed, size, and operating altitudes. But with the outbreak of World War II, further development of this new technology came to a halt as resources were poured into producing military aircraft.

Not surprisingly though, countries on both sides of the war were eager to take advantage of the jet engine. And finally, in 1943, Boeing, in response to US Army Air Force interest in a turbojet-powered bomber, began preliminary studies into creating such as aircraft. The result was Model 450, better known as the Stratojet.

Incredible for its time, the B-47 Stratojet featured six engines, sweptback wings, a bombardier’s station in the nose, remote-controlled tail armament, and two groups of nine Aerojet JATO rocket units to provide extra thrust for takeoff. Making its first flight on December 17, 1947, this high-performance bomber entered service in the early 1950s, equipping a large part of the USAF’s Strategic Air Command. Modified for Tactical Air Command and later for weather reconnaissance, the last B-47s in service were retired in 1969.

Gee Bee

Introduced in 1939, the first jet-powered airplane revolutionized the aviation industry. Significantly eliminating the limitations imposed by the propeller, the jet engine paved the way for increases in aircraft speed, size, and operating altitudes. But with the outbreak of World War II, further development of this new technology came to a halt as resources were poured into producing military aircraft.

Not surprisingly though, countries on both sides of the war were eager to take advantage of the jet engine. And finally, in 1943, Boeing, in response to US Army Air Force interest in a turbojet-powered bomber, began preliminary studies into creating such as aircraft. The result was Model 450, better known as the Stratojet.

Incredible for its time, the B-47 Stratojet featured six engines, sweptback wings, a bombardier’s station in the nose, remote-controlled tail armament, and two groups of nine Aerojet JATO rocket units to provide extra thrust for takeoff. Making its first flight on December 17, 1947, this high-performance bomber entered service in the early 1950s, equipping a large part of the USAF’s Strategic Air Command. Modified for Tactical Air Command and later for weather reconnaissance, the last B-47s in service were retired in 1969.

Staggerwing

Beech Aircraft Corporation was established in 1932. The first airplane it produced was a four-passenger Model 17 biplane. Unlike former biplanes, its wings were staggered; that is, its upper wing lay slightly behind the bottom wing, and it proved to be a fine flyer.

America was in the depths of the Depression at the very time when aircraft and engine designers were producing a profusion of technological ideas. Because it was costly to translate those ideas into reality, established businesses, especially oil companies, sponsored the fledgling aviation industry. Thus it was that the Ethyl Corporation bought Beech’s Model 17, and in 1933 entered it in the Texaco Trophy races in Florida. Not surprisingly, it won.

Meanwhile, Beech engineers continued their refinements. In 1937, they put aileron-type full-length flaps on the lower wings, and ailerons on the upper wings. These increased the aircraft’s controllability and maneuverability enormously, establishing the norm for all future airplanes. Famous aviator Jacqueline Cochran, seen on US #3066, owned a Model D-17W.

During World War II, several versions of the Staggerwing were used as utility transports and communications aircraft by the Army and Navy.

Flying Fortress

On July 28, 1935, Boeing’s Model 299, as it was called at the time, embarked on its first flight from a Seattle airfield. The plane would go on to become one of the most famous used during World War II.

As Seattle Times reporter Richard Smith watched the four-engine plane packed with machine gun mounts pass by, he called it a “Flying Fortress.” Boeing liked the name and trademarked it, designated the plane the B-17 Flying Fortress.

The B-17 was Boeing’s first plane to have a flight deck instead of an open cockpit and it was heavily armed with bombs and five .30-caliber machine guns. It was introduced into battle in 1941 by the British, and as the US joined the war, many more were needed. Over 12,000 were produced for the war. The Japanese called them “four-engine fighters” because they could sustain significant damage but remain in the air. According to General Carl Spaatz, “Without the B-17 we may have lost the war.”

Stearman

Most American and Canadian pilots who served in World War I learned to fly in a Curtiss Jenny. Three decades later, the Stearman Kaydet served the same role during World War II. Its military designation was preceeded by a PT, the “P” indicating a pursuit or fighter plane, the “T” indicating that it was a trainer.

The Stearman Kaydet was developed as a two-seat biplane trainer in 1934 by the Stearman Aircraft Company of Wichita, Kansas. Later that year, Boeing purchased the company and entered the Kaydet into the Army Primary Trainer Competition. The Kaydet won and the Army put in an order for several. When war threatened a few years later, the Army purchased additional planes. By the time Boeing stopped production in 1945, it had turned out over 10,000 Kaydets.

The Stearman Kaydet was a throwback to an earlier age of baling wire and fabric biplanes. An excellent introduction to handling large aircraft, the Kaydet was a sturdy plane, withstanding the many mishaps of inexperienced pilots. However, its size and high center of gravity made it prone to ground looping, a flight characteristic difficult to handle. Consequently, the Kaydet was nicknamed the “Washing Machine” because of the number of would-be pilots that got “washed out” of flight training.

Constellation

The original Constellation was developed in 1939 as a commercial airliner for Transcontinental & Western Air – later Trans-World Airlines (TWA). Designed to be the “fastest, high performance airplane in the world,” its specifications called for a 3,000-mile range and a maximum 18,000-pound payload capacity.

The outbreak of World War II, however, caused the plane to be modified as the C-69 military transport – the first example of which was flown on January 9, 1943. As war demands increased, the plants were commandeered (seized for military use) as they came off the production line. But despite new features, which included hydraulically powered controls and a thermal de-icing system for wing- and tail-unit leading edges, it wasn’t until after the war that the Constellation made its impact on air transportation.

TWA flew its first Constellation on October 1, 1945. The following year, Pan-Am Airways introduced the “Connie,” as it affectionately became known, on the company’s New York-Bermuda route. Extremely efficient with its streamlined fuselage and triple fins and rudders, the Constellation also offered the advantages of a pressurized cabin and more adequate range for transatlantic operation. Before long, it was operating in worldwide services.

Lightning

When the US Army Air Corps issued specifications for a high-altitude interceptor in 1937, Lockheed was already aware of the qualities demanded: speed, ceiling, and firepower combined with the ability to carry enough fuel for superior range were essential. Built to meet these requirements, Lockheed’s P-38 Lightning became one of the most feared and respected aircraft to fly in the Axis skies. Its firepower was lethal and its long range allowed it to accompany bombers to Berlin and beyond.

The Lightning entered service in 1941 and was deployed in Europe, North Africa, and the Pacific during 1942. Throughout the war it gained steadily in performance, demonstrating remarkable versatility. Although it achieved its ultimate effectiveness as an escort, the P-38 was also used extensively as a ground-attack aircraft, as well as during night raids, photograph reconnaissance missions, and to drop smokescreen layers.

It was this combination of power and versatility that gained the P-38 a formidable reputation among the Japanese and Germans, who dubbed it the “fork-tailed devil.” In fact, the Lightning ended the war with more Japanese aircraft to its credit than any other type. And it was the only American fighter built before WWII to still be in production on VJ Day.

Peashooter

In the 21 years between the two World Wars, aviation technology progressed at a remarkable pace. By the 1930s, the biplane had become obsolete, replaced by the speedy new monoplane. Utilizing improved concepts of fighter design, the monoplane achieved a new level of high performance.

This change – from biplane to the monoplane – was marked in 1934 by the entry into service of the Boeing P-26. Nicknamed the “Peashooter,” because of its bulbous lines and its stubby radial engine, the P-26 was the result of close collaboration between Boeing and the US Army. The prototype made its first flight in 1932, and although the P-26 retained an open cockpit, wire-braced wings, and a fixed undercarriage, it was a major step forward in airplane construction. For it was the first plane to feature an all-metal construction, as well as monoplane wings.

With modifications and larger engines, the Peashooter went into service at the beginning of 1934, making the US Air Corps one of the first air forces to use monoplane fighters. For almost five years it represented the front-line equipment of fighter units. And when World War II erupted, about a dozen P-26s were thrown into battle. One of them brought down one of the first Japanese aircraft of the war.

Tri-Motor

In the 21 years between World War I and II, airplane technology changed drastically. Larger, more powerful airplanes required stronger frames and wings. This led to one of the most significant advance – the switch to metal structures.

Throughout the 1920s, most manufacturers used both metal and spruce wood and continued to dress their aircraft in an outer skin of fabric. The first American company to build an all-metal airplane was the Stout Metal Airplane Company, which became a division of Ford Motor Company in 1925. The following year, the company produced a three-engined commercial monoplane powered by 200-horsepower Wright Whirlwind engines. With the installation of newer 300-hp Wright engines later that year, the 11-passenger 4-AT, or Ford Tri-Motor, was born.

Though ahead of its time, the “Tin Goose,” as it was called, was noisy, uncomfortable, and cold – passengers even had to endure being sprayed by mud when the plane landed. Nonetheless, with a maximum take-off weight of 10,130 pounds, a cruising speed of 107 mph, and a range of 570 miles, it was the best there was. In all, 200 Tri-Motors were built from 1926 to 1933. At the peak of production in 1929, the company turned out four planes a week, producing a total of 78 airplanes that year alone.

DC-3

When the first DC-3 rolled down the runway in 1934, few knew it was destined to become the most famous commercial airplane ever built. Though not the first low-wing monoplane in a world still dominated by biplanes, it was immediately popular with airlines in America and Europe. It was easy to fly and had the passenger comforts so lacking in the Tri-Motor.

With the outbreak of World War II, the Douglas Aircraft Corporation went into immediate mass-production. Altogether, 10,000 DC-3s ferried thousands of US and British servicemen as C-47 Skytrains, and Dakotas respectively. Converted to civilian use after the war, the DC-3 became the world’s principal airliner and biggest moneymaker in its class. As late as 1965, DC-3s still outnumbered all other types of airliners.

More than anything else, the DC-3 was an indestructible workhorse because it was a stress-skinned “fail-safe” airplane. Prior to DC-3s, airplanes had a lifespan of about 6,000 hours and had a tendency to come apart at the seams when a structural member broke. When a wing spar in the DC-3 broke, the weight was picked up by alternate spars. This type of construction eliminated catastrophic chain reactions and reduced fatigue, which, in turn, enormously increased its safety and its lifespan.

Clipper

In most mind, Pan American Airlines and “Clipper” are synonymous. Though not the first American international airline, Pan Am was perhaps the most successful, and was certainly a leader in the industry.

The company got its start in 1927, flying mail between Key West, Florida, and Havana, Cuba. Scheduled passenger service followed the next year. And by 1929, with Charles Lindbergh’s help, it had mapped out a 12,000-mile route between North, South, and Central America.

By 1936, Pan Am was ready to develop its transoceanic service. Boeing was recruited to build a comfortable 74-passenger airplane with a range of 3,500 miles – a monumental request. Although Boeing considered declining the offer, instead it took the XB-15 high-wing – predecessor of the Flying Fortress – and added a luxurious double-decker hull. In order to lift the craft, crew, and payload, it installed four of the most powerful engines available – Wright Twin Cyclone 14-cylinder engines.

The six glamorous 314 Clippers that began service in 1939 flew only a few short years, but garnered many firsts. Not only did they fly the first transpacific flight in 1936, but also the first transatlantic flight in 1939, and the first round-the-world flight in 1947.

Jenny

Bicycle manufacturer Glenn Curtiss began his career in aviation design developing seaplanes. In 1915, he was awarded the first contract to build US Navy planes. Believig in the future of flight, he sought to design an airplane which could be mass-produced. The result was his eight-cylinder OX-5 engine combined with features from a British aircraft designer. Designated the JN-4, it became affectionately known as the “Jenny.”

Created at the onset of World War I, the Jenny played a major role in the fighting – the only American mass-produced aircraft to do so. During the war years, Curtiss manufactured more than 6,400 units for the US Army Air Corps and US Navy (at $5,000 each) as well as over 2,000 units for other Allied governments, including Great Britain and Russia.

Because of the quantities produced, 95% of all American and Canadian WWI pilots earned their wings in a Jenny. Hundreds were sold as surplus after the Armistice. Barnstormers quickly traveled the country performing daring feats, thereby introducing ordinary Americans to the thrills of aviation. Many more became familiar with aviation when the US Post Office issued the 24¢ Jenny stamp to inaugurate the world’s first regularly scheduled transportation of mail by air.

Wildcat

The Grumman Aerospace Corporation was founded by Leroy Grumman, a US industrialist and master designer of US fighter planes. During the 1930s Grumman’s inventions – retractable landing gear and a folding wing later used on the Wildcat carrier fighter – earned him countless US Navy contracts. In 1938, negotiations between the Navy and Grumman led to the development for the XF4F-3 (“X” designating “experimental”). Officially dubbed the “Wildcat,” it became the first of the famous Grumman “cat” family.

By December 1941, 245 Wildcats had entered US service, and for the next two years they served as the main US Navy and Marine Corps fighter. In addition to an increased wingspan, the F4F also sported “squared” wing and tail tips. Necessary for additional lifting surface required by heavier aircraft, this feature eventually became a “trademark” of the Grumman aircraft.

Although not particularly outstanding in terms of performance, the Wildcat was staunchly rugged and well-armed. And in the hands of an experienced pilot, it proved the equal of the highly effective Japanese Zero. Able to compile a distinguished combat record, Grumman aircraft reportedly shot down more than 60% of enemy aircraft in the Pacific Theater during World War II.