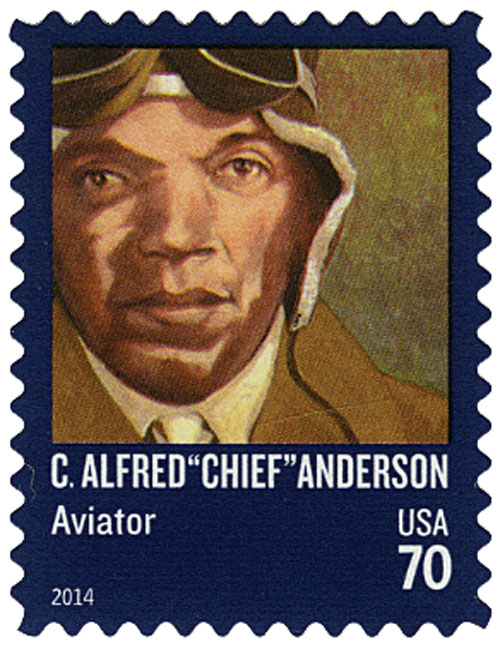

# 4879 - 2014 70c Distinguished Americans: C. Alfred 'Chief' Anderson

City: Bryn Mawr, PA, Anderson’s hometown

Quantity: 20,000,000

Printed By: Ashton Potter USA Ltd.

Printing Method: Lithographed in sheets of 160 with 8 panes of 20 per sheet

Perforations: Serpentine Die Cut 10 ¾ X 11

Self-adhesive

Formation Of Tuskegee Airmen

On March 19, 1941, the War Department ordered the creation of the the 99th Pursuit Squadron, better known as the Tuskegee Airmen.

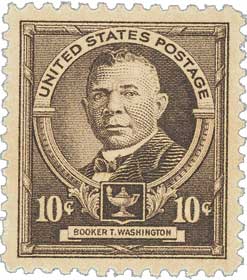

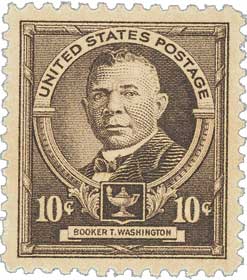

The Tuskegee Normal School (later Tuskegee Institute) was founded on July 4, 1881. Its founders were Lewis Adams, a former slave, and George W. Campbell, a former slaveholder, who both believed African American education was of the utmost importance. They selected 25-year-old Booker T. Washington to serve as their first president. Under Washington’s leadership, the school went from using a rundown church to an institute spanning 2,300 acres by the early 20th century.

In 1940, there were only 124 African-American pilots in the U.S. Many had participated in the Civilian Pilot Training Program through the Tuskegee Institute, taught by Charles Alfred “Chief” Anderson. But none of them were allowed to fly for the military. The War Department didn’t want to accept African American pilots, so it set a high bar of flight experience and education that it didn’t expect any could meet. But they were wrong, and the U.S. Army Air Corps received a large number of applications from African American men who met their strict requirements.

Ultimately the War Department changed their mind and, on March 19, 1941, ordered the creation of America’s first black military pilot squadron. A few days later, the 99th Flying Squadron was established. The first graduates never saw combat, but as the war progressed later trainees served as escorts for heavy bombers and on bombing raids. In June 1941, they became the 99th Fighter Squadron, complete with ground crew.

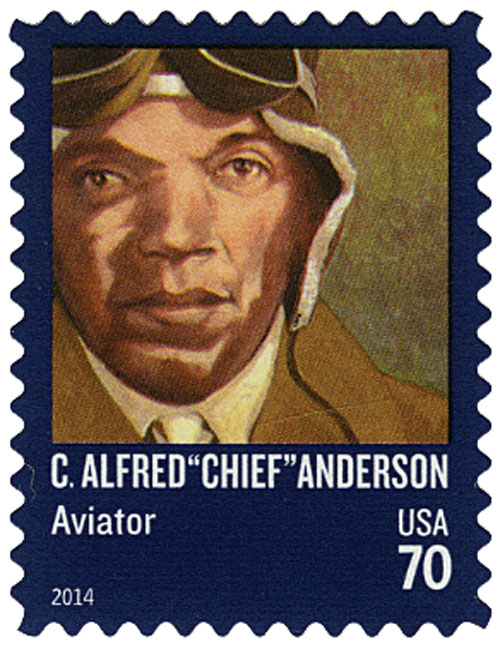

City: Bryn Mawr, PA, Anderson’s hometown

Quantity: 20,000,000

Printed By: Ashton Potter USA Ltd.

Printing Method: Lithographed in sheets of 160 with 8 panes of 20 per sheet

Perforations: Serpentine Die Cut 10 ¾ X 11

Self-adhesive

Formation Of Tuskegee Airmen

On March 19, 1941, the War Department ordered the creation of the the 99th Pursuit Squadron, better known as the Tuskegee Airmen.

The Tuskegee Normal School (later Tuskegee Institute) was founded on July 4, 1881. Its founders were Lewis Adams, a former slave, and George W. Campbell, a former slaveholder, who both believed African American education was of the utmost importance. They selected 25-year-old Booker T. Washington to serve as their first president. Under Washington’s leadership, the school went from using a rundown church to an institute spanning 2,300 acres by the early 20th century.

In 1940, there were only 124 African-American pilots in the U.S. Many had participated in the Civilian Pilot Training Program through the Tuskegee Institute, taught by Charles Alfred “Chief” Anderson. But none of them were allowed to fly for the military. The War Department didn’t want to accept African American pilots, so it set a high bar of flight experience and education that it didn’t expect any could meet. But they were wrong, and the U.S. Army Air Corps received a large number of applications from African American men who met their strict requirements.

Ultimately the War Department changed their mind and, on March 19, 1941, ordered the creation of America’s first black military pilot squadron. A few days later, the 99th Flying Squadron was established. The first graduates never saw combat, but as the war progressed later trainees served as escorts for heavy bombers and on bombing raids. In June 1941, they became the 99th Fighter Squadron, complete with ground crew.