1917 Washington violet, perf 10, Type I

# 493 - 1917 Washington violet, perf 10, Type I

$2.75 - $152.00

U.S. #493

1916-22 3¢ Washington

Type I

1916-22 3¢ Washington

Type I

Issue Date: July 23, 1917

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Watermark: None

Perforation: 10 vertically

Color: Violet

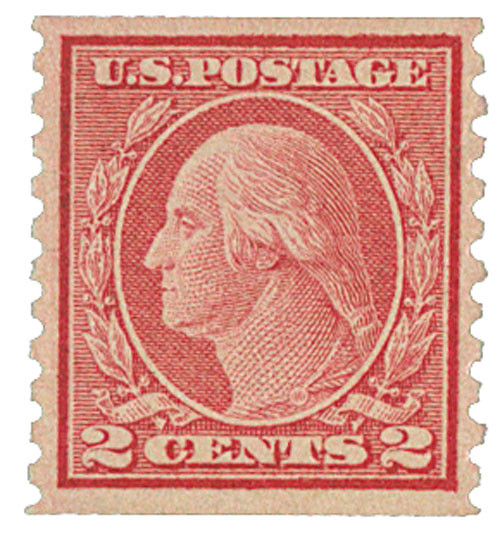

U.S. #493 increased in demand with the onset of Americas entry into World War I. In order to prevent the plates from deteriorating too quickly, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing created a new master die. The one used for U.S. #493 is referred to as Type I. This stamp also had a wider range of color shades than previous 3¢ issues, ranging from reddish violet to dull violet.

Type I

The Series of 1916-22 2¢ Washington Type I stamps of this series have several distinguishing features: a pronounced white line underneath Washingtons ear, and the bottom two strands of hair behind his ear are shorter than the ones above it. Other features are often less distinct than found on Type II or Type III dies.

U.S. #493

1916-22 3¢ Washington

Type I

1916-22 3¢ Washington

Type I

Issue Date: July 23, 1917

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Watermark: None

Perforation: 10 vertically

Color: Violet

U.S. #493 increased in demand with the onset of Americas entry into World War I. In order to prevent the plates from deteriorating too quickly, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing created a new master die. The one used for U.S. #493 is referred to as Type I. This stamp also had a wider range of color shades than previous 3¢ issues, ranging from reddish violet to dull violet.

Type I

The Series of 1916-22 2¢ Washington Type I stamps of this series have several distinguishing features: a pronounced white line underneath Washingtons ear, and the bottom two strands of hair behind his ear are shorter than the ones above it. Other features are often less distinct than found on Type II or Type III dies.