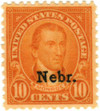

1929 10c Monroe, orange yellow, Kansas-Nebraska overprints

# 679 - 1929 10c Monroe, orange yellow, Kansas-Nebraska overprints

MSRP:

Was:

Now:

$27.00 - $1,000.00

(You save

)

(No reviews yet)

Write a Review

Write a Review

679 - 1929 10c Monroe, orange yellow, Kansas-Nebraska overprints

| Image | Condition | Price | Qty | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mint Plate Block

ⓘ

Usually ships within 30 days.

Usually ships within 30 days.

$ 1,000.00

|

$ 1,000.00 |

|

0

|

|

Mint Stamp(s)

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 125.00

|

$ 125.00 |

|

1

|

|

Mint Stamp(s)

Fine

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 187.50

|

$ 187.50 |

|

2

|

|

Mint Stamp(s)

Fine, Never Hinged

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 225.00

|

$ 225.00 |

|

3

|

|

Mint Stamp(s)

Very Fine

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 245.00

|

$ 245.00 |

|

4

|

|

Mint Stamp(s)

Very Fine, Never Hinged

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 270.00

|

$ 270.00 |

|

5

|

|

Used Single Stamp(s)

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 55.00

|

$ 55.00 |

|

6

|

|

Mint Stamp(s)

Extra Fine

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 292.50

|

$ 292.50 |

|

7

|

|

Mint Stamp(s)

Extra Fine, Never Hinged

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 380.00

|

$ 380.00 |

|

8

|

|

Unused Stamp(s)

small flaws

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 75.00

|

$ 75.00 |

|

9

|

|

Used Stamp(s)

small flaws

ⓘ

Ships in 1-3 business days.

Ships in 1-3 business days.

$ 27.00

|

$ 27.00 |

|

10

|

|

Unused Plate Block

small flaws

ⓘ

Usually ships within 30 days.

Usually ships within 30 days.

$ 625.00

|

$ 625.00 |

|

11

|

Mounts - Click Here

| Mount | Price | Qty |

|---|

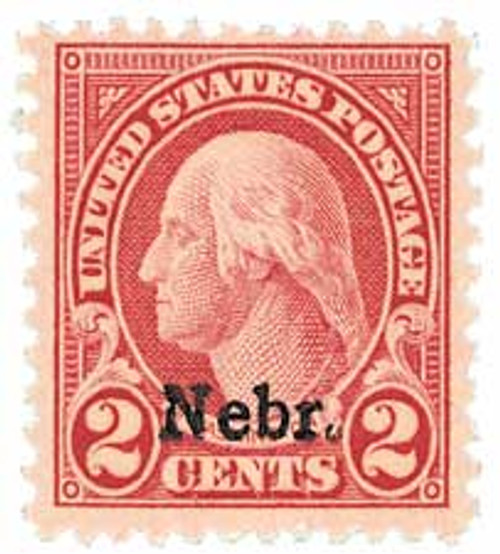

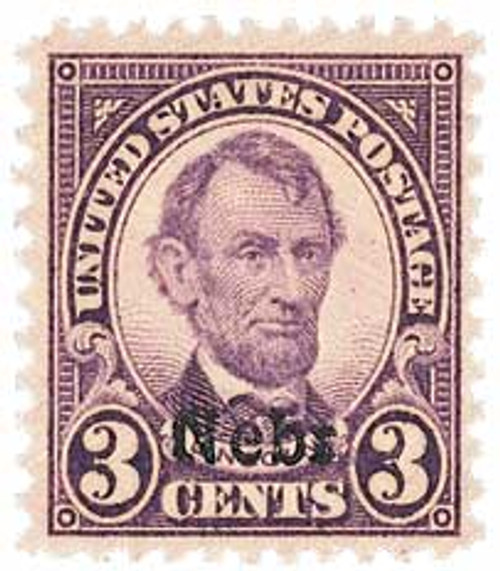

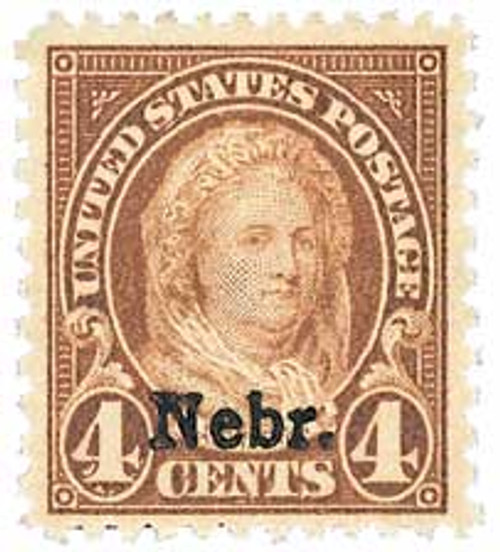

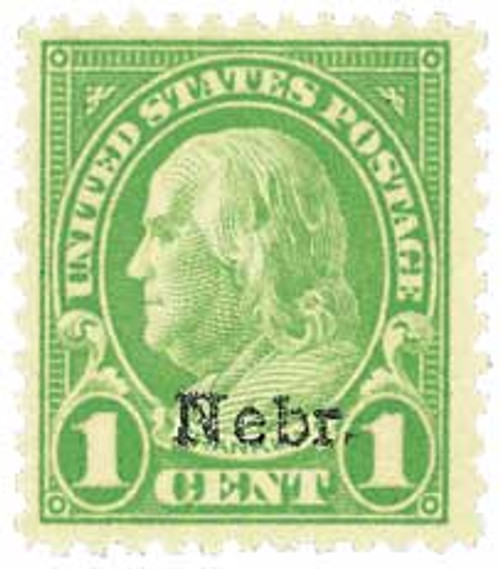

U.S. #679

1929 Kansas-Nebraska Overprints

10¢ Nebraska

1929 Kansas-Nebraska Overprints

10¢ Nebraska

Issued: May 1, 1929

First City: Tecumseh, NE

Quantity Issued: 1,890,000

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Perforation: 11 x 10.5

Color: Orange yellow

First City: Tecumseh, NE

Quantity Issued: 1,890,000

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Perforation: 11 x 10.5

Color: Orange yellow

!