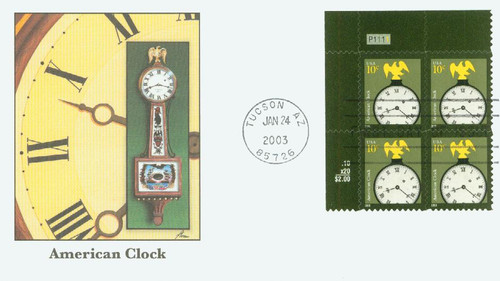

# 3762 - 2006 10c American Clock

10¢ American Clock

American Design

City: Independence, OR

Printed By: American Packaging Corp. for Sennett Security Products

Printing Method: Photogravure

Perforations: 9 ¾ Vertically

Color: Green, yellow, and black

First National Daylight Savings Time In The U.S.

Long before modern societies adopted daylight savings time, ancient civilizations based their activities around the Sun. The Romans used water clocks with scales that changed for different times of the year.

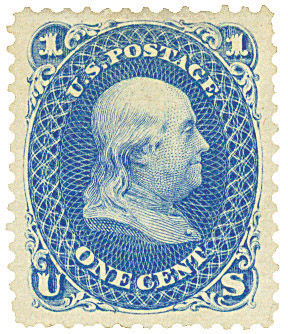

As early as 1784 Benjamin Franklin promoted the idea of adjusting schedules to coincide with the Sun’s light. In his 1784 satirical essay, “An Economical Project for the Diminishing the Cost of Light,” Franklin jokingly suggested that the people of Paris could use less candles if they woke up earlier.

The first official proposal for something similar to daylight savings time came in 1895. New Zealand scientist George Vernon Hudson proposed that clocks shift two hours forward in October and two hours backward in March. While there was some support for this idea, it never materialized.

A decade later, British builder William Willett had his own idea. He suggested that clocks be moved ahead 20 minutes on the four Sundays in April, and then switch back the same way in September. Willett’s proposal eventually reached Parliament but was never made into law.

In America, President William Howard Taft encouraged the passage of a June 1909 bill for his home city of Cincinnati, Ohio, to become the first city in America to adopt daylight savings time. On May 1, 1910, clocks in the city were set ahead one hour and would then fall back one hour on October 1.

Then in 1916, as the world was embroiled in war, many nations recognized the need to save fuel for electricity. Germany and Austria were the first to adopt a daylight savings program when they moved their clocks ahead one hour at 11:00 p.m. on April 30, 1916. Several other nations quickly followed suit that year and the year after.

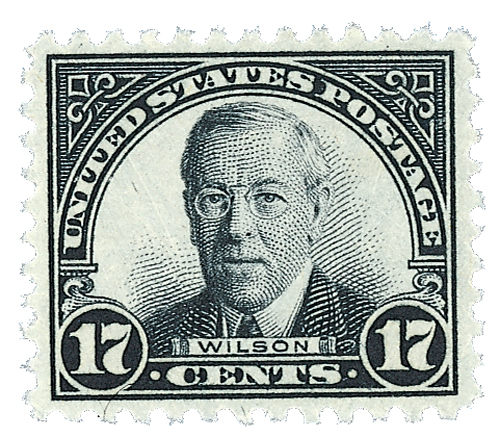

Pennsylvania industrialist Robert Garland was visiting the United Kingdom and learned of this concept, which was then known as “fast time.” He returned to America and proposed its adoption. President Woodrow Wilson approved the idea and it was signed into law on March 19, 1918. America first entered daylight savings time later that month, on March 31, 1918. America observed daylight savings time for seven months that year and the next. But with the war over, it grew unpopular and was repealed. Many other nations also abandoned daylight savings time after the war, though Canada, the United Kingdom, and France continued to use it, as well as a few American cities.

As America entered another war in the 1940s, the idea of daylight savings time reemerged. President Franklin Roosevelt signed legislation instituting year-round daylight savings time, also called “War Time,” beginning in February 1942. This remained in effect until the war ended in 1945.

For 20 years there were no more laws concerning daylight savings, which created significant confusion, particularly for travellers and broadcasters. Then Congress passed the Uniform Time Act of 1966. This law stated that daylight savings time would begin on the last Sunday of April and end the last Sunday of October, though states could pass an ordinance to be exempt from it. In the decades since there have been changes to the law, so that now in America daylight savings time begins on the second Sunday in March and ends on the first Sunday in November.

Click here to read the first two American daylight savings time acts.

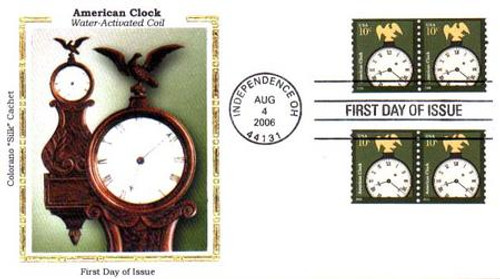

10¢ American Clock

American Design

City: Independence, OR

Printed By: American Packaging Corp. for Sennett Security Products

Printing Method: Photogravure

Perforations: 9 ¾ Vertically

Color: Green, yellow, and black

First National Daylight Savings Time In The U.S.

Long before modern societies adopted daylight savings time, ancient civilizations based their activities around the Sun. The Romans used water clocks with scales that changed for different times of the year.

As early as 1784 Benjamin Franklin promoted the idea of adjusting schedules to coincide with the Sun’s light. In his 1784 satirical essay, “An Economical Project for the Diminishing the Cost of Light,” Franklin jokingly suggested that the people of Paris could use less candles if they woke up earlier.

The first official proposal for something similar to daylight savings time came in 1895. New Zealand scientist George Vernon Hudson proposed that clocks shift two hours forward in October and two hours backward in March. While there was some support for this idea, it never materialized.

A decade later, British builder William Willett had his own idea. He suggested that clocks be moved ahead 20 minutes on the four Sundays in April, and then switch back the same way in September. Willett’s proposal eventually reached Parliament but was never made into law.

In America, President William Howard Taft encouraged the passage of a June 1909 bill for his home city of Cincinnati, Ohio, to become the first city in America to adopt daylight savings time. On May 1, 1910, clocks in the city were set ahead one hour and would then fall back one hour on October 1.

Then in 1916, as the world was embroiled in war, many nations recognized the need to save fuel for electricity. Germany and Austria were the first to adopt a daylight savings program when they moved their clocks ahead one hour at 11:00 p.m. on April 30, 1916. Several other nations quickly followed suit that year and the year after.

Pennsylvania industrialist Robert Garland was visiting the United Kingdom and learned of this concept, which was then known as “fast time.” He returned to America and proposed its adoption. President Woodrow Wilson approved the idea and it was signed into law on March 19, 1918. America first entered daylight savings time later that month, on March 31, 1918. America observed daylight savings time for seven months that year and the next. But with the war over, it grew unpopular and was repealed. Many other nations also abandoned daylight savings time after the war, though Canada, the United Kingdom, and France continued to use it, as well as a few American cities.

As America entered another war in the 1940s, the idea of daylight savings time reemerged. President Franklin Roosevelt signed legislation instituting year-round daylight savings time, also called “War Time,” beginning in February 1942. This remained in effect until the war ended in 1945.

For 20 years there were no more laws concerning daylight savings, which created significant confusion, particularly for travellers and broadcasters. Then Congress passed the Uniform Time Act of 1966. This law stated that daylight savings time would begin on the last Sunday of April and end the last Sunday of October, though states could pass an ordinance to be exempt from it. In the decades since there have been changes to the law, so that now in America daylight savings time begins on the second Sunday in March and ends on the first Sunday in November.

Click here to read the first two American daylight savings time acts.