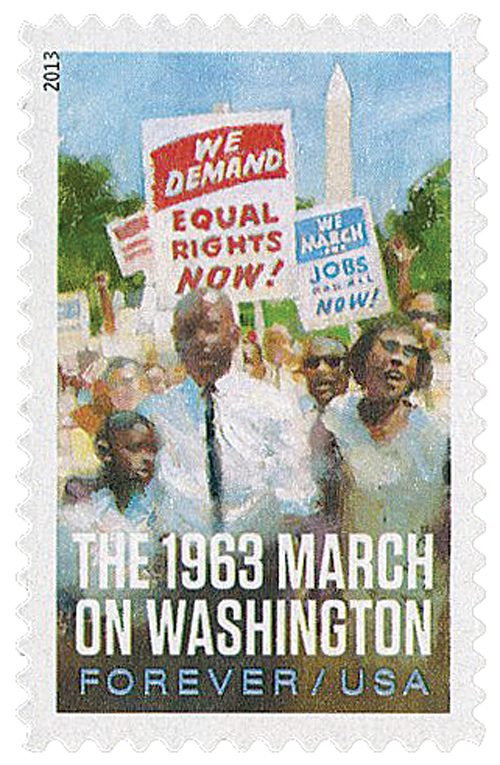

# 4804 - 2013 First-Class Forever Stamp - The 1963 March on Washington

U.S. # 4804

2013 46¢ March on Washington

Civil Rights

March On Washington And Martin Luther King, Jr’s “I Have A Dream” Speech

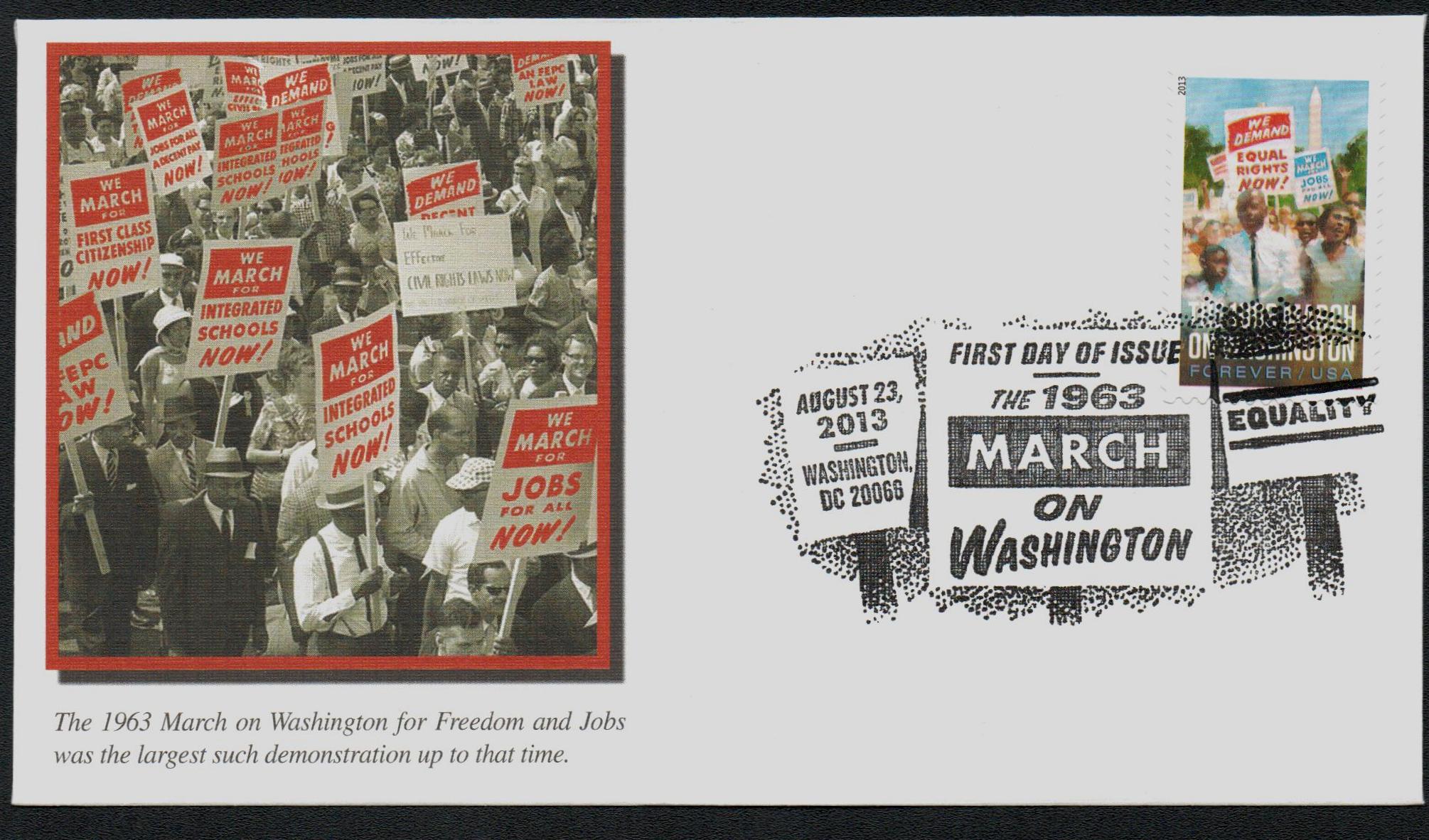

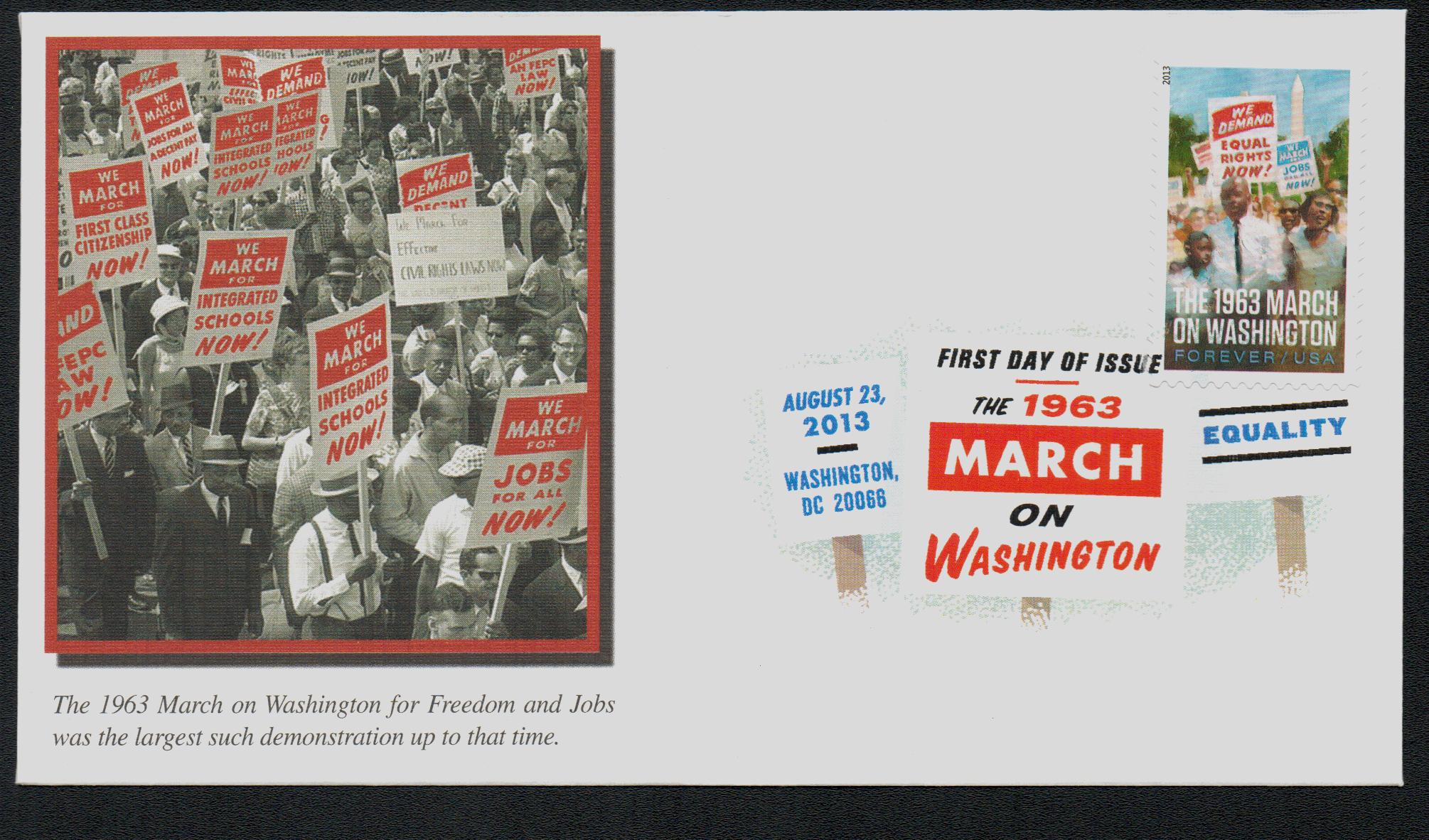

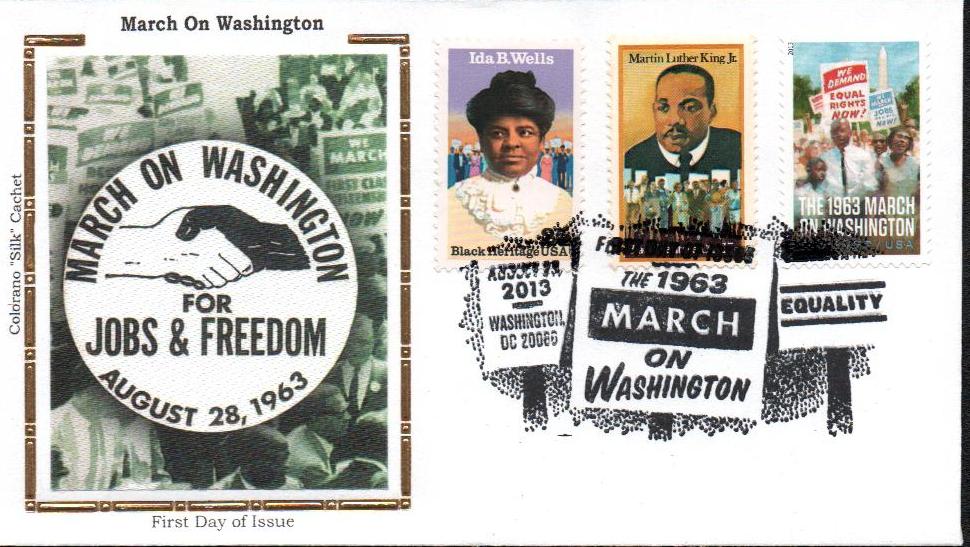

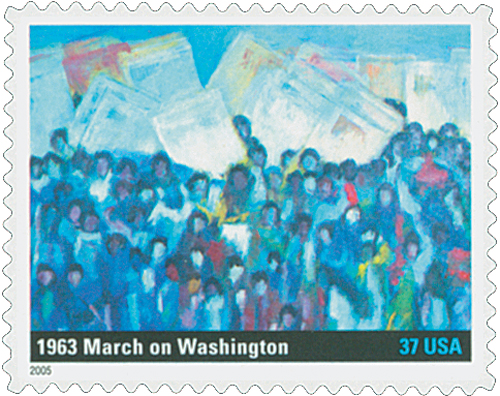

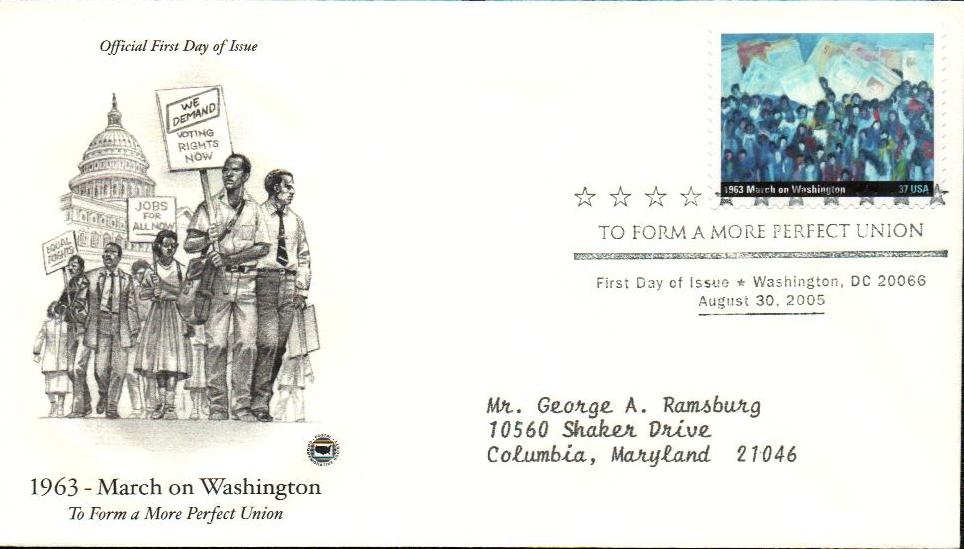

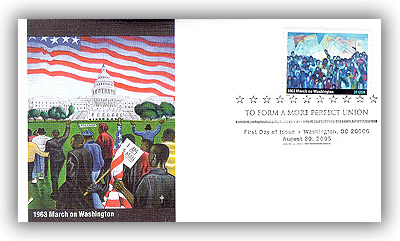

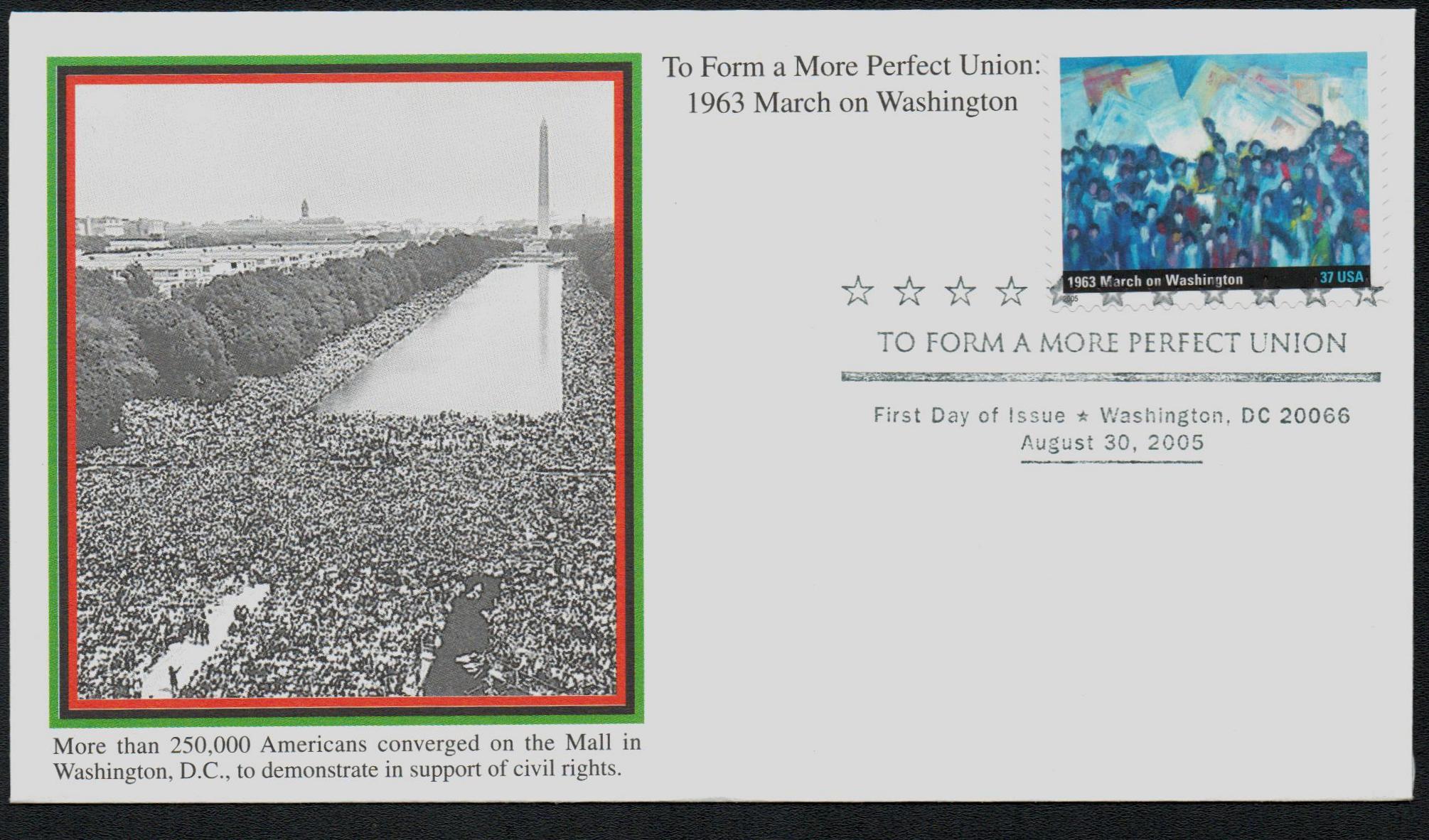

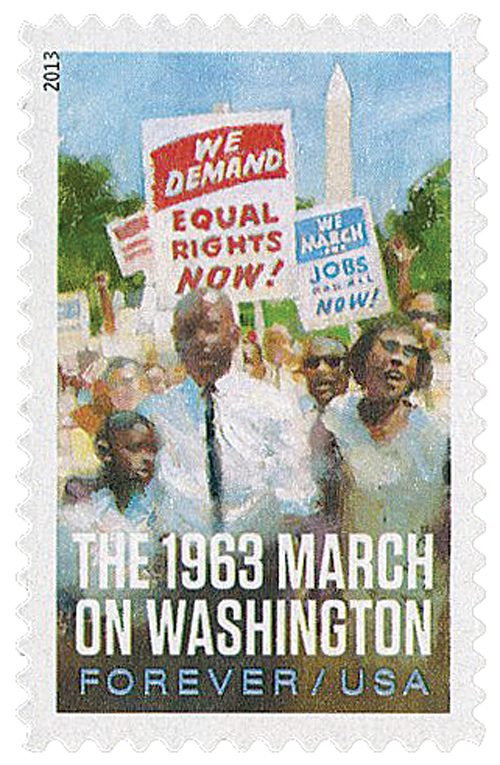

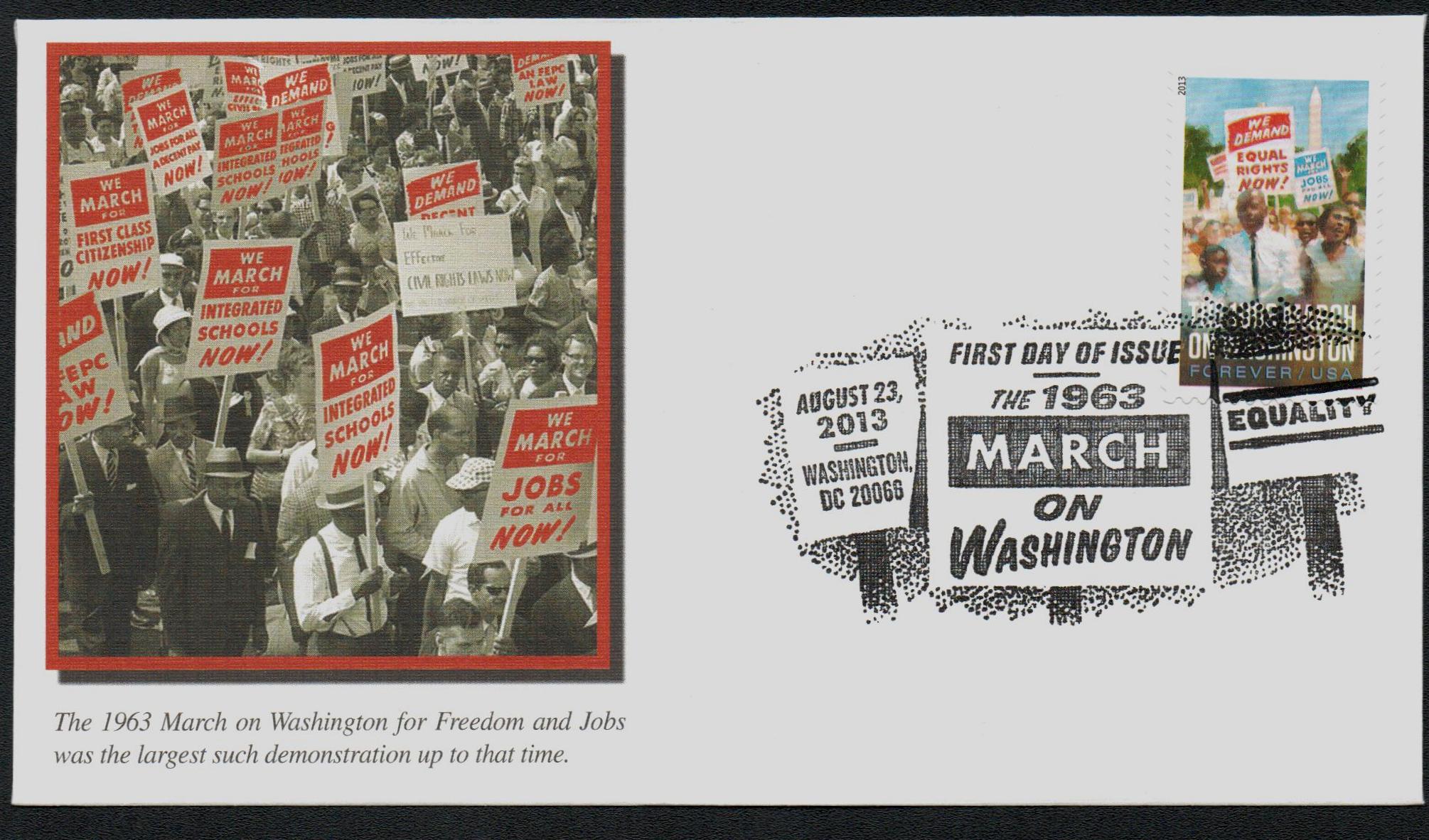

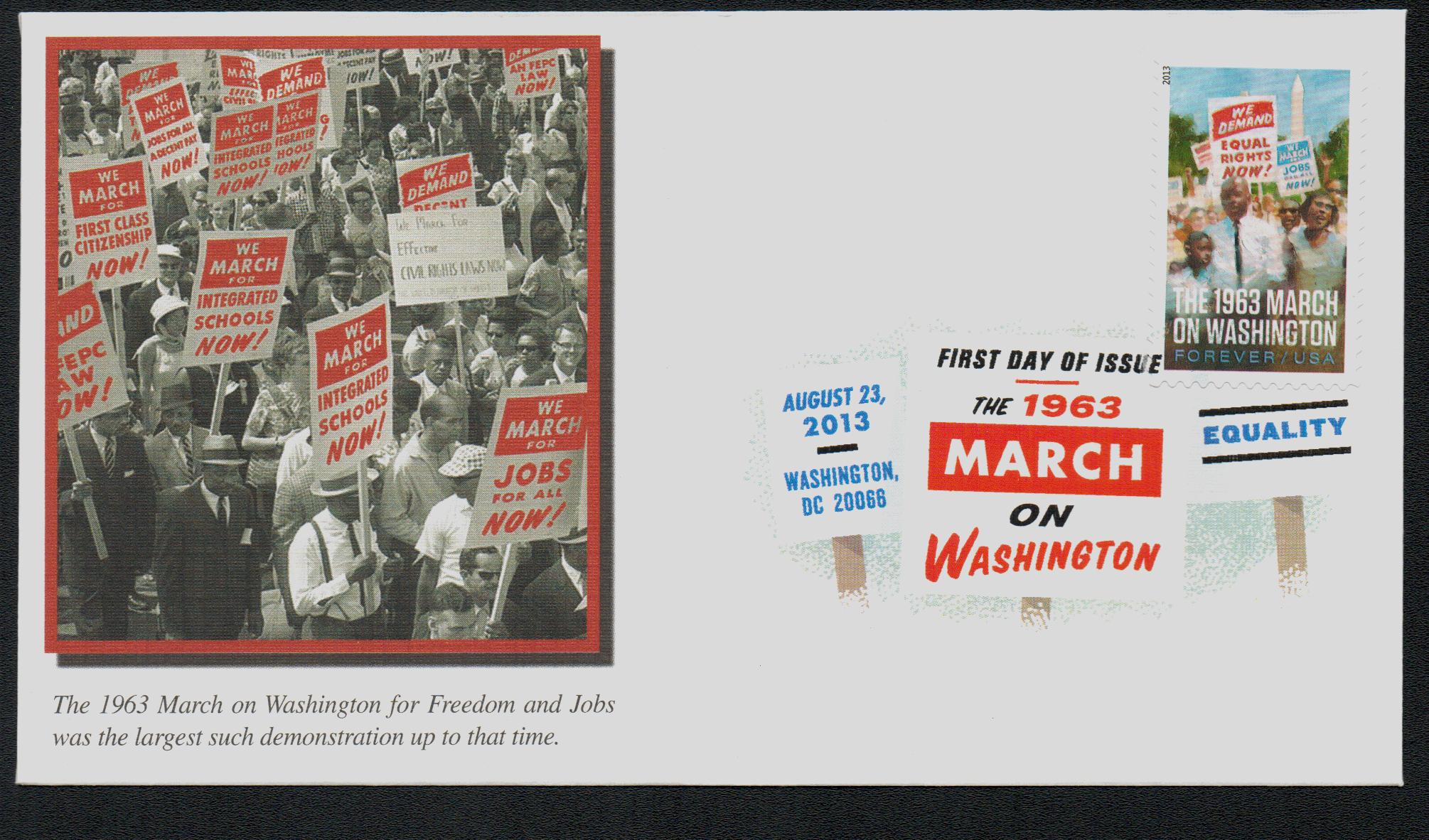

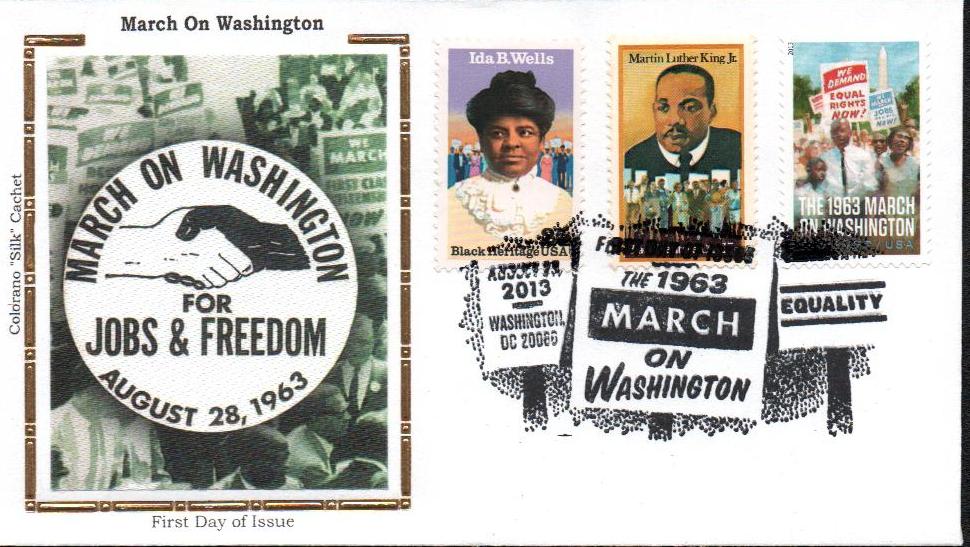

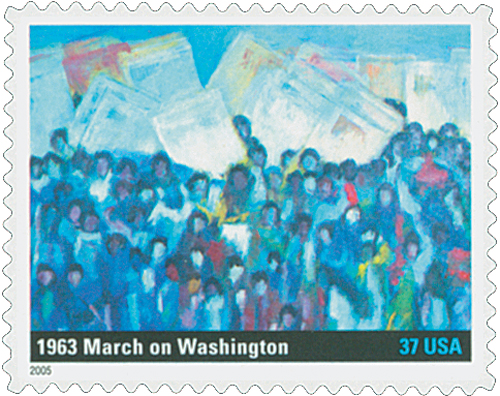

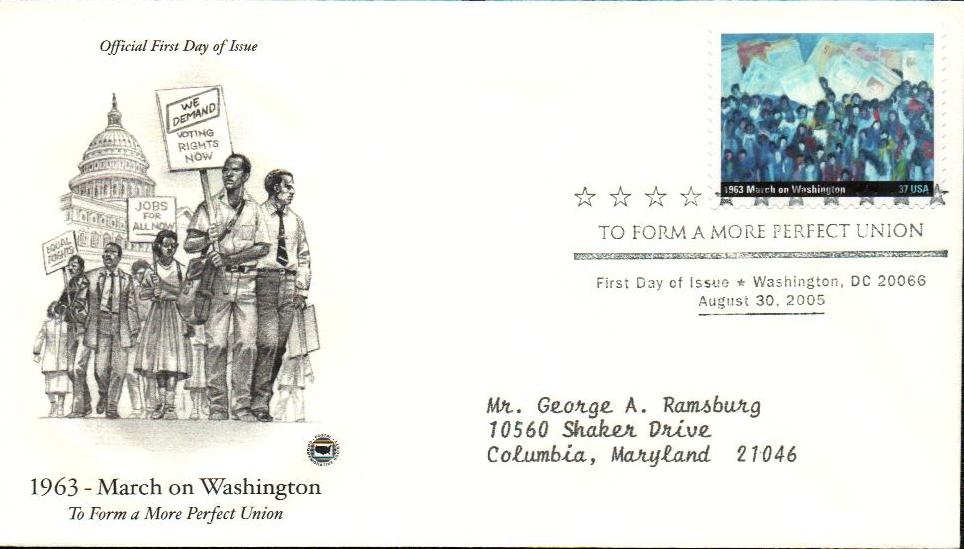

As African Americans struggled against segregation and mistreatment, Civil Rights leaders organized the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963.

Tensions ran high during the 1960s as segregation and violence against African Americans were spreading unchecked in the South. Civil rights demonstrations calling for equality swept the nation. The most famous was the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

When President John F. Kennedy proposed a civil rights bill in 1963, the march was developed to urge Congress to pass the legislation. The march was the idea of A. Philip Randolph, the president of the International Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first black US labor union. The “Big Six” – civil rights leaders Randolph, Martin Luther King, Jr., James Farmer Jr., Whitney Young, Jr., Roy Wilkins, and John Lewis, organized the march. Among the stated goals of the day were: passing civil rights legislation, ending segregation in schools, protecting against police brutality, and increasing access to jobs.

President Kennedy feared the march could end in violence and suggested it was ill-timed. But organizers insisted it go on, and Randolph claimed: “Frankly, I have never engaged in any direct-action movement which did not seem ill-timed.” In the end, Kennedy endorsed the march, but tasked his brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, with coordinating the event to oversee security. Fifteen thousand paratroopers were put on alert, but there was no violence. The march’s organizer’s also decided to end the march at the Lincoln Memorial instead of the Capitol building so Congress wouldn’t feel attacked.

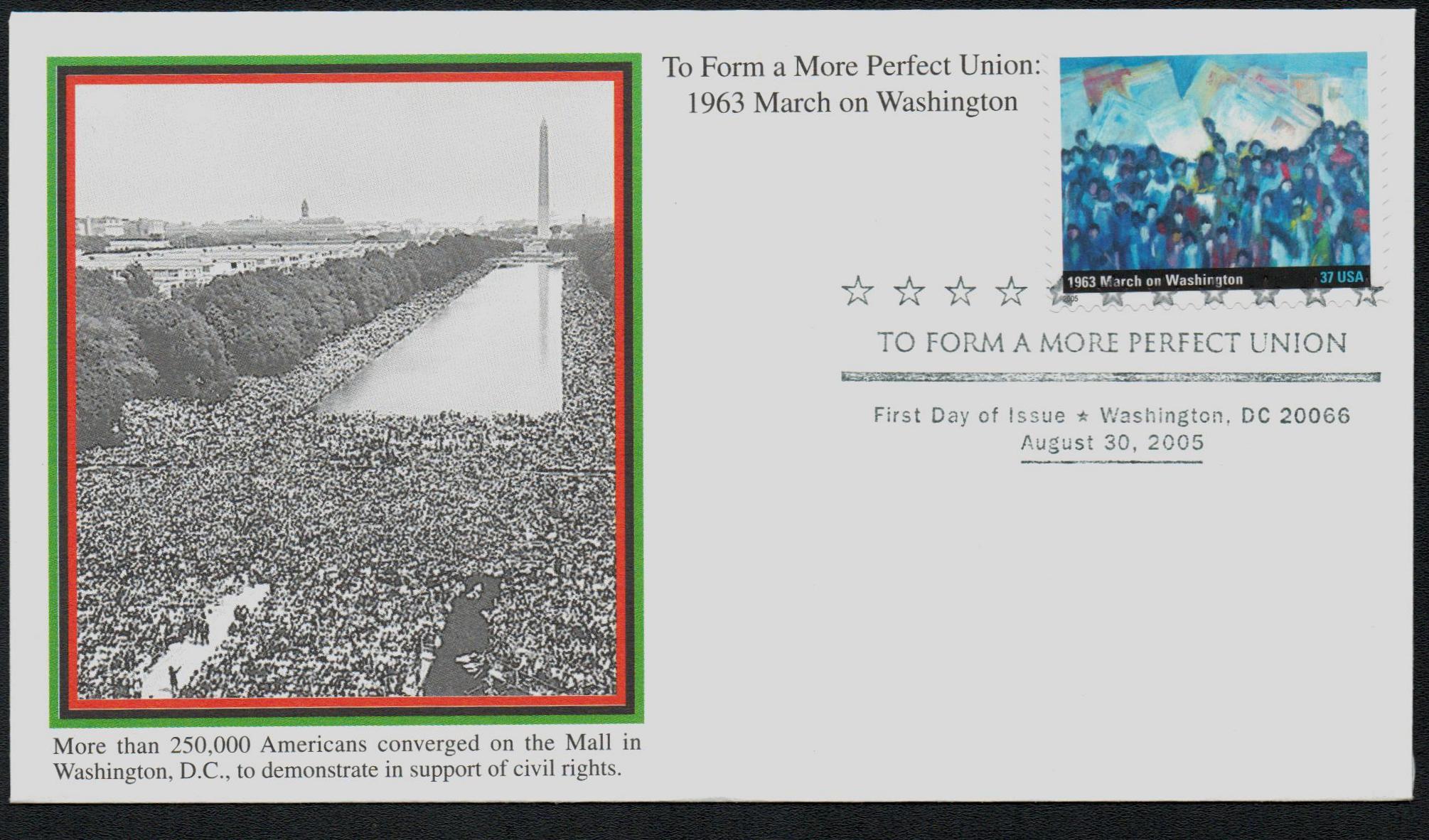

“Freedom trains” and “Freedom buses” brought people to Washington from all across the country. The march attracted over 250,000 people, making it the largest demonstration held in the nation’s capital up to that time. Demonstrators marched from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial. Several popular entertainers also turned out to perform in support of the cause, including Marian Anderson, Joan Baez, and Bob Dylan.

Randolph was the first speaker of the day and closed his speech saying, “We here today are only the first wave. When we leave, it will be to carry the civil rights revolution home with us into every nook and cranny of the land, and we shall return again and again to Washington in ever-growing numbers until total freedom is ours.” Bayard Rustin, Roy Wilkins, John Lewis, Daisy Lee Bates, Ossie Davis, and Ruby Dee followed him.

The highlight of the march was King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, given at the Lincoln Memorial. All the other speakers wanted to go earlier in the day, expecting the press would leave early, leaving King to speak last. His original speech was four minutes long, but he ended up speaking for 16 minutes.

As he looked out over the crowd, King realized the end of his speech wasn’t what he wanted to say, so he began preaching. In his stirring speech, King defined the civil rights movement’s moral basis. His plea for equality conveyed a sense of urgency to members of the crowd. On that day, King envisioned justice for all races.

The march was widely televised, gaining national attention. Congress passed Kennedy’s civil rights bill in 1964 and later the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The act called for an end to racial discrimination in education, employment, and in public places. King, whose struggle for equality changed America forever, was awarded the Nobel peace prize the following year.

Click here to view video from the march and here to view King’s speech.

U.S. # 4804

2013 46¢ March on Washington

Civil Rights

March On Washington And Martin Luther King, Jr’s “I Have A Dream” Speech

As African Americans struggled against segregation and mistreatment, Civil Rights leaders organized the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963.

Tensions ran high during the 1960s as segregation and violence against African Americans were spreading unchecked in the South. Civil rights demonstrations calling for equality swept the nation. The most famous was the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

When President John F. Kennedy proposed a civil rights bill in 1963, the march was developed to urge Congress to pass the legislation. The march was the idea of A. Philip Randolph, the president of the International Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first black US labor union. The “Big Six” – civil rights leaders Randolph, Martin Luther King, Jr., James Farmer Jr., Whitney Young, Jr., Roy Wilkins, and John Lewis, organized the march. Among the stated goals of the day were: passing civil rights legislation, ending segregation in schools, protecting against police brutality, and increasing access to jobs.

President Kennedy feared the march could end in violence and suggested it was ill-timed. But organizers insisted it go on, and Randolph claimed: “Frankly, I have never engaged in any direct-action movement which did not seem ill-timed.” In the end, Kennedy endorsed the march, but tasked his brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, with coordinating the event to oversee security. Fifteen thousand paratroopers were put on alert, but there was no violence. The march’s organizer’s also decided to end the march at the Lincoln Memorial instead of the Capitol building so Congress wouldn’t feel attacked.

“Freedom trains” and “Freedom buses” brought people to Washington from all across the country. The march attracted over 250,000 people, making it the largest demonstration held in the nation’s capital up to that time. Demonstrators marched from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial. Several popular entertainers also turned out to perform in support of the cause, including Marian Anderson, Joan Baez, and Bob Dylan.

Randolph was the first speaker of the day and closed his speech saying, “We here today are only the first wave. When we leave, it will be to carry the civil rights revolution home with us into every nook and cranny of the land, and we shall return again and again to Washington in ever-growing numbers until total freedom is ours.” Bayard Rustin, Roy Wilkins, John Lewis, Daisy Lee Bates, Ossie Davis, and Ruby Dee followed him.

The highlight of the march was King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, given at the Lincoln Memorial. All the other speakers wanted to go earlier in the day, expecting the press would leave early, leaving King to speak last. His original speech was four minutes long, but he ended up speaking for 16 minutes.

As he looked out over the crowd, King realized the end of his speech wasn’t what he wanted to say, so he began preaching. In his stirring speech, King defined the civil rights movement’s moral basis. His plea for equality conveyed a sense of urgency to members of the crowd. On that day, King envisioned justice for all races.

The march was widely televised, gaining national attention. Congress passed Kennedy’s civil rights bill in 1964 and later the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The act called for an end to racial discrimination in education, employment, and in public places. King, whose struggle for equality changed America forever, was awarded the Nobel peace prize the following year.

Click here to view video from the march and here to view King’s speech.