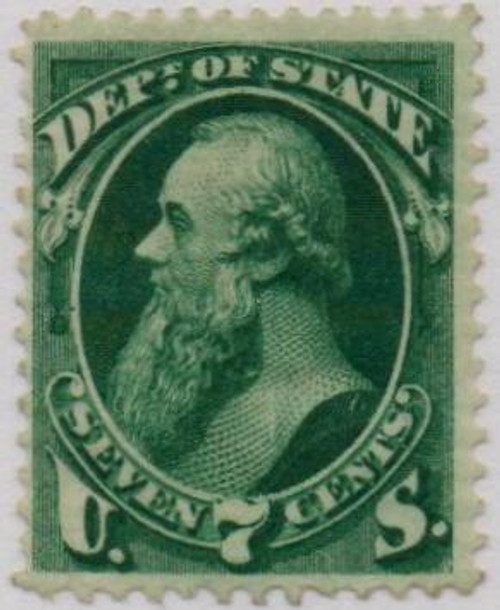

# O68 - 1873 $2 Green and Black, Department of State, Seward, Hard Paper

1873 $2 Seward

Official Stamp – Department of State

Birth Of William H. Seward

Seward was a bright child that enjoyed school (it was reported that instead of running away from school to go home, he’d run away from home to go to school). He went on to attend Union College, taking time off to teach in Georgia before returning and graduating with high honors in 1820.

Seward then studied law, passed the bar, and moved to Auburn, New York, where he met newspaper publisher and political boss Thurlow Weed, who would remain a close ally for many years. It was during his time in Auburn that Seward became increasingly interested in politics. With Weed’s support, Seward was elected to the New York State Senate in 1830 with the Anti-Masonic Party. In the coming years, he emerged as a leader of the Whig Party, but lost both his senate seat and a run for the governorship in 1834.

With his political prospects gone, Seward followed his family’s wishes and returned to practicing law. He also worked for the Holland Land Company, a group of Dutch investors that bought large tracts of land in western New York.

Seward’s break from politics was brief. In 1838, Weed convinced him to run for governor of New York again, and this time he won. Seward served two terms as governor and focused much of his attention on prison reform and improving education. Seward left the governorship in 1842 in considerable debt and had to return to practicing law once again.

1873 $2 Seward

Official Stamp – Department of State

Birth Of William H. Seward

Seward was a bright child that enjoyed school (it was reported that instead of running away from school to go home, he’d run away from home to go to school). He went on to attend Union College, taking time off to teach in Georgia before returning and graduating with high honors in 1820.

Seward then studied law, passed the bar, and moved to Auburn, New York, where he met newspaper publisher and political boss Thurlow Weed, who would remain a close ally for many years. It was during his time in Auburn that Seward became increasingly interested in politics. With Weed’s support, Seward was elected to the New York State Senate in 1830 with the Anti-Masonic Party. In the coming years, he emerged as a leader of the Whig Party, but lost both his senate seat and a run for the governorship in 1834.

With his political prospects gone, Seward followed his family’s wishes and returned to practicing law. He also worked for the Holland Land Company, a group of Dutch investors that bought large tracts of land in western New York.

Seward’s break from politics was brief. In 1838, Weed convinced him to run for governor of New York again, and this time he won. Seward served two terms as governor and focused much of his attention on prison reform and improving education. Seward left the governorship in 1842 in considerable debt and had to return to practicing law once again.