# 2816 - 1994 29c Black Heritage: Dr. Allison Davis

U.S. #2816

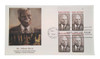

1994 29¢ Dr. Allison Davis

Black Heritage

- 17th stamp in the Black Heritage Series

Stamp Category: Commemorative

Set: Black Heritage

Value: 29¢, rate for first-class mail

First Day of Issue: February 1, 1994

First Day City: Williamstown, Massachusetts

Quantity Issued: 155,500,00

Printed by: Stamp Venturers

Printing Method: Engraved

Format: Panes of 20 in intaglio plates of 240

Perforations: 11.1

Color: Red brown and brown

Why the stamp was issued: Issued on the first day of Black History Month. The stamp had been proposed by the Williams College Bicentennial Commission, which wanted a stamp to honor the university’s 200th anniversary in 1993. Rather than picturing a historic building on a postal card in the Historic Preservation Series, as was the norm, the commission wanted a stamp picturing a famous alumnus. They selected Davis, who overcame segregation and discrimination to become a respected anthropologist and teacher. While the stamp wasn’t issued in time for that anniversary, it was issued the following year for the Black Heritage Series because, as the USPS stated, Davis “was chosen as a stamp subject because of his pioneering work in education and other social sciences.”

About the stamp design: The stamp was designed by veteran stamp artist Christopher Calle. It was his first stamp in the Black Heritage series. Calle enjoyed creating portraits and focusing on a person’s most notable features, in this case, Davis’ mustache. The portrait was based on a photo taken by Davis’ son in 1983. The original photo included shelves of books in the background. At the suggestion of the USPS art director, Calle filled the background with diagonal lines, triangles, and diamond shapes. As art director Richard Sheaff explained, it was “based on the (visual) vocabulary of African art, which is very rich and interesting.”

Special design details: The Allison Davison stamp differed from other stamps that came before it in the Black Heritage Series in several ways. While most of the other stamps included a second element, such as a small figure or scene, this stamp only pictured Davis. It was also printed by intaglio, while the ones that came before had been printed by gravure or offset-intaglio. Finally, it was issued in panes of 20, while the others had been issued in panes of 50.

First Day City: Williamstown, Massachusetts – Davis attended Williams College in the town.

About the Black Heritage Series: The first Black Heritage stamp was issued in 1978 and pictured Harriet Tubman. She was also the first African American woman to be honored on a US stamp. The US Postal Service has continued to issue stamps in this series every year since then.

History the stamp represents: Dr. William Boyd Allison Davis was born on October 14, 1902, in Washington, DC. Dr. Davis came from a family that was familiar with activism. His grandfather had been an abolitionist lawyer, and his father led an anti-lynching committee of the NAACP.

Davis graduated as valedictorian from his high school in 1920 and again was valedictorian upon his graduation from Williams College in 1924. From there, he went to teach in rural Virginia. It was there that he witnessed first-hand the effects of social class in education. He realized that “teaching in the standard manner made no sense to these poor and poorly schooled rural blacks. I decided that I didn’t know anything to teach them since our backgrounds were so different, yet I wanted to do something to affect such students.”

Davis was concerned over this experience and decided to return to school to explore how he could make a difference. In 1931, he went to Harvard to study social anthropology. There, he enveloped himself in exhaustive study of class and race in the Deep South. He worked with others to conduct field research that revealed a color-caste system. Davis used this research to conduct a comparative study of the effects of this system on young African Americans in two cities. The result of these studies was two books, Children of Bondage (1940) and Deep South (1941).

In 1942, Davis received his doctorate from the University of Chicago, where he served as a faculty member for the next 40 years. He was the first African American to hold a full faculty position at a major white university. He was also one of the first African American anthropologists in the country. Davis served on the faculty of the Department of Education and Committee on Human Development.

Davis worked closely with other social scientists there to conduct extensive studies. They studied infant and child rearing in both white and black families. Davis also embarked on a major study of standardized intelligence tests that were used in elementary schools. In his book Social-Class Influences upon Learning, Davis argued that these tests were biased towards middle-class students. In 1951, he co-authored an analysis of class-based student responses to the questions found on 10 intelligence tests.

Davis challenged the cultural bias of the testing system and fought for the understanding of human potential without regard to race or class. He considered his work on intelligence testing to be the most successful aspect of his career. His research led many cities to abolish or revise intelligence tests. As he later recalled, “This one time I got what I wanted: a direct effect on society from social science research.” Davis’s research also helped inspire the Head Start Program.

Widely acclaimed, Davis received numerous awards, including the University of Chicago’s John Dewey Distinguished Service Professor of Education. He was also named Educator of the Year in 1971. During the 60s, Dr. Davis served on the President’s Commission on Civil Rights and later as vice chairman of the Department of Labor’s Commission on Manpower Retraining. His final book, Leadership, Love, and Aggression, examined four prominent black leaders through the lens of his class and caste studies. Davis died on November 21, 1983.

U.S. #2816

1994 29¢ Dr. Allison Davis

Black Heritage

- 17th stamp in the Black Heritage Series

Stamp Category: Commemorative

Set: Black Heritage

Value: 29¢, rate for first-class mail

First Day of Issue: February 1, 1994

First Day City: Williamstown, Massachusetts

Quantity Issued: 155,500,00

Printed by: Stamp Venturers

Printing Method: Engraved

Format: Panes of 20 in intaglio plates of 240

Perforations: 11.1

Color: Red brown and brown

Why the stamp was issued: Issued on the first day of Black History Month. The stamp had been proposed by the Williams College Bicentennial Commission, which wanted a stamp to honor the university’s 200th anniversary in 1993. Rather than picturing a historic building on a postal card in the Historic Preservation Series, as was the norm, the commission wanted a stamp picturing a famous alumnus. They selected Davis, who overcame segregation and discrimination to become a respected anthropologist and teacher. While the stamp wasn’t issued in time for that anniversary, it was issued the following year for the Black Heritage Series because, as the USPS stated, Davis “was chosen as a stamp subject because of his pioneering work in education and other social sciences.”

About the stamp design: The stamp was designed by veteran stamp artist Christopher Calle. It was his first stamp in the Black Heritage series. Calle enjoyed creating portraits and focusing on a person’s most notable features, in this case, Davis’ mustache. The portrait was based on a photo taken by Davis’ son in 1983. The original photo included shelves of books in the background. At the suggestion of the USPS art director, Calle filled the background with diagonal lines, triangles, and diamond shapes. As art director Richard Sheaff explained, it was “based on the (visual) vocabulary of African art, which is very rich and interesting.”

Special design details: The Allison Davison stamp differed from other stamps that came before it in the Black Heritage Series in several ways. While most of the other stamps included a second element, such as a small figure or scene, this stamp only pictured Davis. It was also printed by intaglio, while the ones that came before had been printed by gravure or offset-intaglio. Finally, it was issued in panes of 20, while the others had been issued in panes of 50.

First Day City: Williamstown, Massachusetts – Davis attended Williams College in the town.

About the Black Heritage Series: The first Black Heritage stamp was issued in 1978 and pictured Harriet Tubman. She was also the first African American woman to be honored on a US stamp. The US Postal Service has continued to issue stamps in this series every year since then.

History the stamp represents: Dr. William Boyd Allison Davis was born on October 14, 1902, in Washington, DC. Dr. Davis came from a family that was familiar with activism. His grandfather had been an abolitionist lawyer, and his father led an anti-lynching committee of the NAACP.

Davis graduated as valedictorian from his high school in 1920 and again was valedictorian upon his graduation from Williams College in 1924. From there, he went to teach in rural Virginia. It was there that he witnessed first-hand the effects of social class in education. He realized that “teaching in the standard manner made no sense to these poor and poorly schooled rural blacks. I decided that I didn’t know anything to teach them since our backgrounds were so different, yet I wanted to do something to affect such students.”

Davis was concerned over this experience and decided to return to school to explore how he could make a difference. In 1931, he went to Harvard to study social anthropology. There, he enveloped himself in exhaustive study of class and race in the Deep South. He worked with others to conduct field research that revealed a color-caste system. Davis used this research to conduct a comparative study of the effects of this system on young African Americans in two cities. The result of these studies was two books, Children of Bondage (1940) and Deep South (1941).

In 1942, Davis received his doctorate from the University of Chicago, where he served as a faculty member for the next 40 years. He was the first African American to hold a full faculty position at a major white university. He was also one of the first African American anthropologists in the country. Davis served on the faculty of the Department of Education and Committee on Human Development.

Davis worked closely with other social scientists there to conduct extensive studies. They studied infant and child rearing in both white and black families. Davis also embarked on a major study of standardized intelligence tests that were used in elementary schools. In his book Social-Class Influences upon Learning, Davis argued that these tests were biased towards middle-class students. In 1951, he co-authored an analysis of class-based student responses to the questions found on 10 intelligence tests.

Davis challenged the cultural bias of the testing system and fought for the understanding of human potential without regard to race or class. He considered his work on intelligence testing to be the most successful aspect of his career. His research led many cities to abolish or revise intelligence tests. As he later recalled, “This one time I got what I wanted: a direct effect on society from social science research.” Davis’s research also helped inspire the Head Start Program.

Widely acclaimed, Davis received numerous awards, including the University of Chicago’s John Dewey Distinguished Service Professor of Education. He was also named Educator of the Year in 1971. During the 60s, Dr. Davis served on the President’s Commission on Civil Rights and later as vice chairman of the Department of Labor’s Commission on Manpower Retraining. His final book, Leadership, Love, and Aggression, examined four prominent black leaders through the lens of his class and caste studies. Davis died on November 21, 1983.