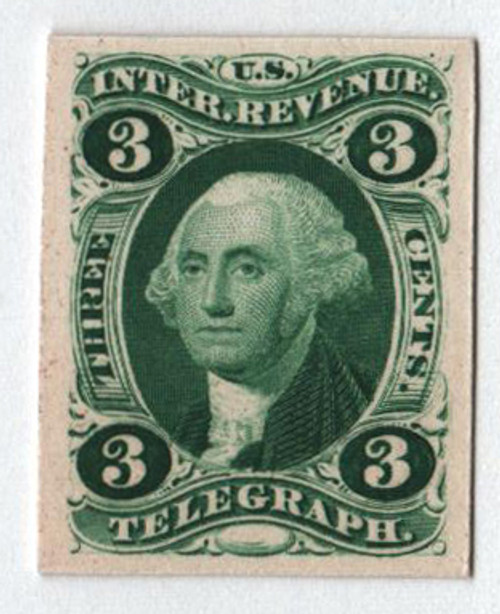

# R4 - 1862-71 1c US Internal Revenue Stamp - Telegraph, old paper, red

A Revolution in Communication!

A transcontinental line linked European and U.S. telegraphs in 1861– changing the world forever. R#4 paid the 1¢ revenue tax levied to help fund the Civil War. Historic, fun and affordable.

First Commercial Telegraph Service

Prior to the 1830s, the word “telegraph” was used to describe any system of sending messages over a distance without there being a physical exchange between the sender and receiver. There were only a few such systems in place and they were “optical telegraphs,” which didn’t send messages electronically, rather they were sent visually through the use of visible signals. These systems couldn’t be used at night or in bad weather.

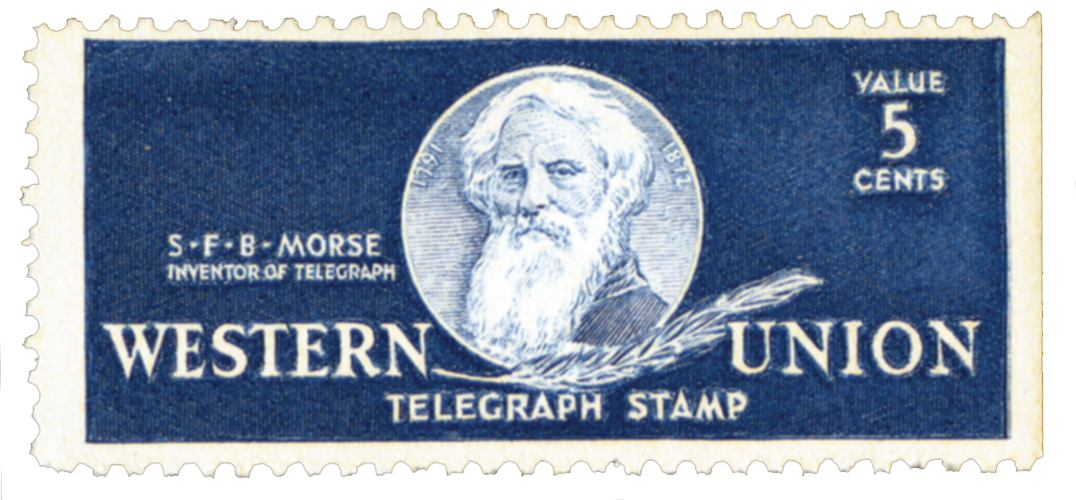

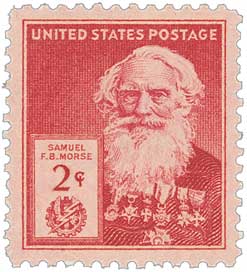

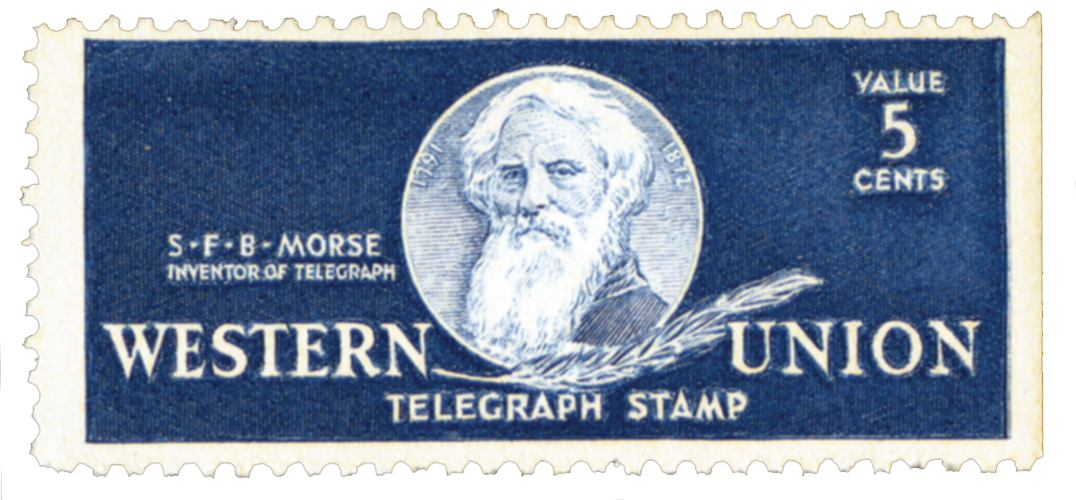

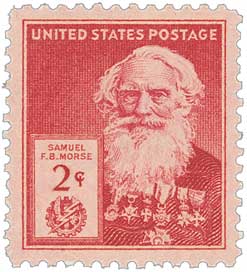

In January 1837, US Naval Captain Samuel C. Reid petitioned Congress to establish a national telegraph system. A month later, Congress asked Secretary of the Treasury Levi Woodbury to look into the possibility of creating such a system. Woodbury issued a request for suggestions and received more than a dozen responses. Nearly all of these responses were for optical telegraphs. The only one that wasn’t, came from Samuel F.B. Morse, an art professor from New York University. Morse suggested an “entirely new mode of telegraphic communication” that he had thought of during an ocean trip five years earlier – an electromagnetic telegraph.

In his enthusiastic letter to Woodbury, Morse said this his telegraph could work day or night in any weather, better than any other form of telegraph. He also said it would be able to record messages; messages could be received even if there wasn’t a person present to receive it. Morse also pointed out that because telegraphs were “another mode of accomplishing the principal object for which the mail is established, to wit: the rapid and regular transmission of intelligence, [it seemed] most natural to connect a telegraphic system with the Post Office Department.”

Morse traveled to Washington, DC, in February 1838 to show his device to Congress. While some of the congressmen were convinced of the importance of his invention, the majority were not and he failed to receive the funding for a test run that he had hoped for.

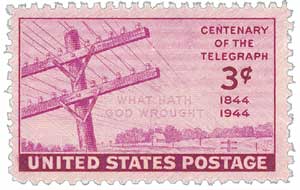

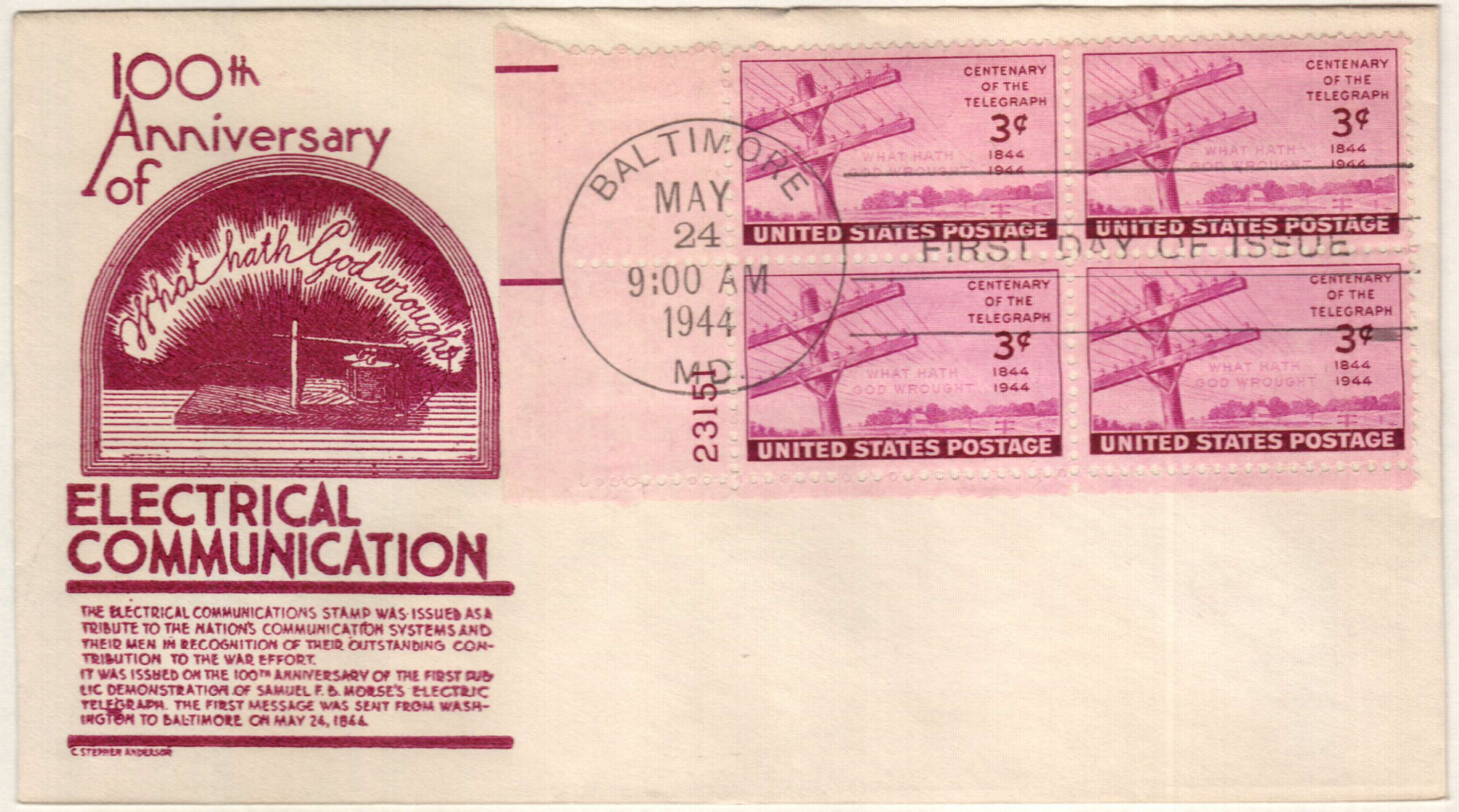

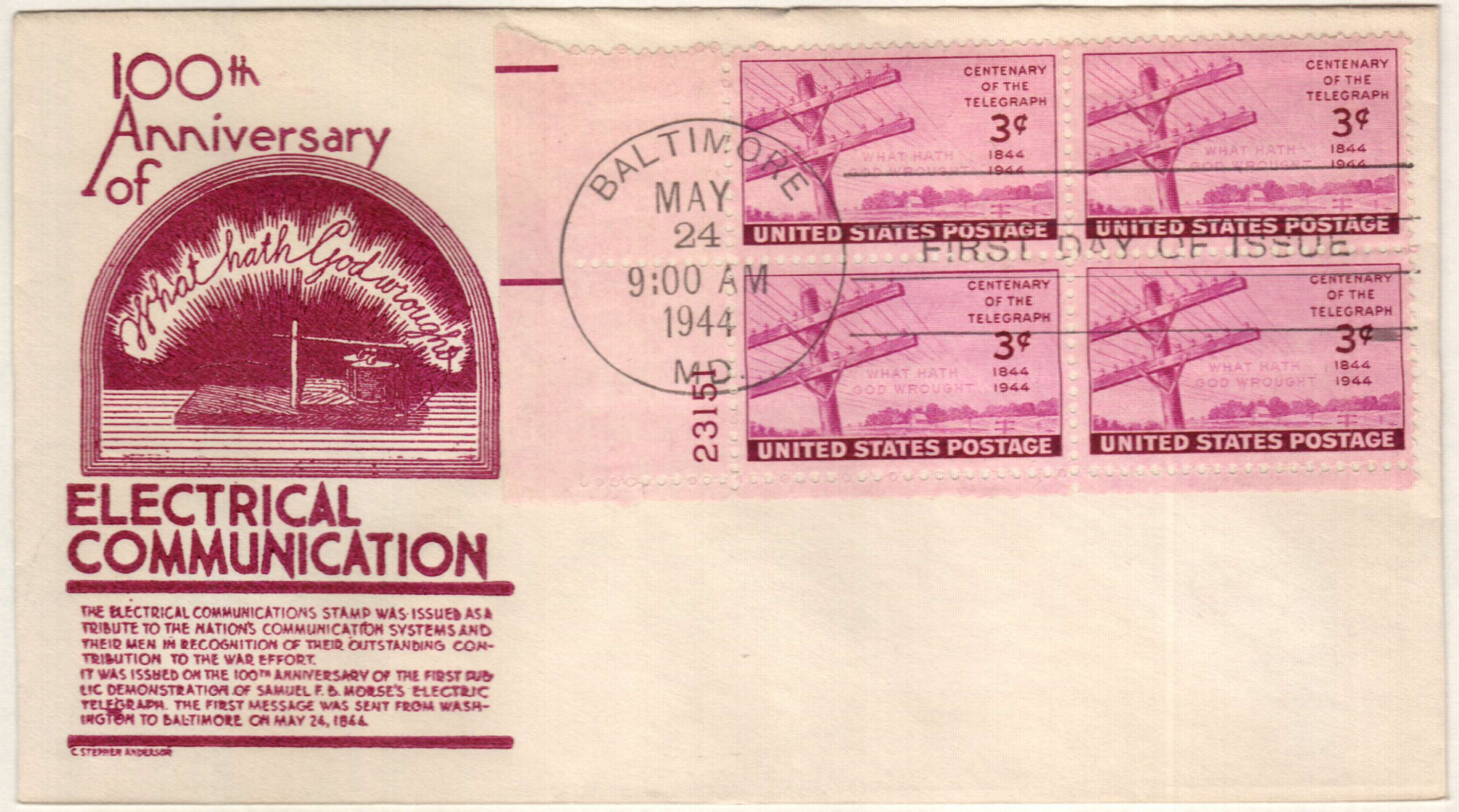

Morse was called back to Washington five years later to show them his device again. This time he received much more positive support. On March 3, 1843, Congress passed an act granting $30,000 to test “the capacity and usefulness” of Morse’s telegraph. Morse then went about constructing the telegraph line between the US Capitol in Washington, DC, and the train depot in Baltimore, Maryland. On May 24, 1844, he transmitted his first message – “What hath God wrought,” a quote from the Book of Numbers in the Bible.

The announcement of Morse’s success fascinated the nation. One reporter stated that it “commences a new era in the process of correspondence… Information will be literally winged with the rapidity of lightning.” Morse and his assistant then spent several months sending messages across the telegraph day and night, showing how it could be used in a number of ways.

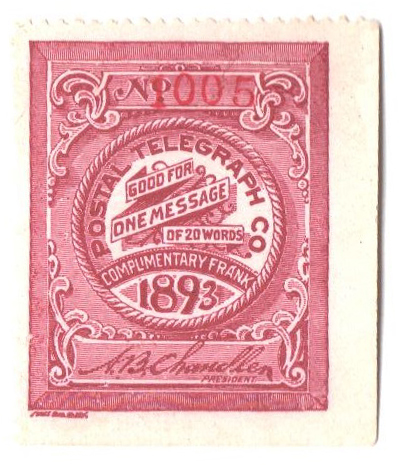

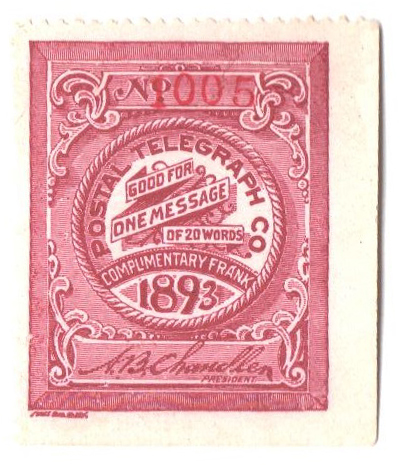

The telegraph office in Washington was moved to the post office in October 1844, and in March of the following year, Congress granted $8,000 for the expense and maintenance of the line under the postmaster general. Then, on April 1, 1845, the telegraph line was opened to the public. Samuel Morse was made superintendent of the system and an employee of the Post Office Department. The new service had a postage rate of one-quarter of one cent for each character of the message, paid by the sender. Once the messages were received at the other end, they were written down and given to postmen for delivery.

The initial rate had been set at half the price Morse had suggested, to encourage people to use it. It would be lowered even more the following year. However, few people actually used the telegraph service and proved unprofitable in its first year. Because it was unprofitable, Congress didn’t want to pay to establish more lines. But Morse and others recognized the importance and usefulness of the telegraph, so they formed their own company and built their own lines from their own funds. By late 1846, telegraph lines connected Washington and New York City, while other lines stretched to Boston and Pittsburgh.

Eventually, the private company took over operation of the Washington-Baltimore line, authorized to do so as long as they didn’t charge the government for their service. From then until World War I, telegraph service would remain in private hands. Telegraph service remained in use through the end of the century but would come to an end in 2013.

A Revolution in Communication!

A transcontinental line linked European and U.S. telegraphs in 1861– changing the world forever. R#4 paid the 1¢ revenue tax levied to help fund the Civil War. Historic, fun and affordable.

First Commercial Telegraph Service

Prior to the 1830s, the word “telegraph” was used to describe any system of sending messages over a distance without there being a physical exchange between the sender and receiver. There were only a few such systems in place and they were “optical telegraphs,” which didn’t send messages electronically, rather they were sent visually through the use of visible signals. These systems couldn’t be used at night or in bad weather.

In January 1837, US Naval Captain Samuel C. Reid petitioned Congress to establish a national telegraph system. A month later, Congress asked Secretary of the Treasury Levi Woodbury to look into the possibility of creating such a system. Woodbury issued a request for suggestions and received more than a dozen responses. Nearly all of these responses were for optical telegraphs. The only one that wasn’t, came from Samuel F.B. Morse, an art professor from New York University. Morse suggested an “entirely new mode of telegraphic communication” that he had thought of during an ocean trip five years earlier – an electromagnetic telegraph.

In his enthusiastic letter to Woodbury, Morse said this his telegraph could work day or night in any weather, better than any other form of telegraph. He also said it would be able to record messages; messages could be received even if there wasn’t a person present to receive it. Morse also pointed out that because telegraphs were “another mode of accomplishing the principal object for which the mail is established, to wit: the rapid and regular transmission of intelligence, [it seemed] most natural to connect a telegraphic system with the Post Office Department.”

Morse traveled to Washington, DC, in February 1838 to show his device to Congress. While some of the congressmen were convinced of the importance of his invention, the majority were not and he failed to receive the funding for a test run that he had hoped for.

Morse was called back to Washington five years later to show them his device again. This time he received much more positive support. On March 3, 1843, Congress passed an act granting $30,000 to test “the capacity and usefulness” of Morse’s telegraph. Morse then went about constructing the telegraph line between the US Capitol in Washington, DC, and the train depot in Baltimore, Maryland. On May 24, 1844, he transmitted his first message – “What hath God wrought,” a quote from the Book of Numbers in the Bible.

The announcement of Morse’s success fascinated the nation. One reporter stated that it “commences a new era in the process of correspondence… Information will be literally winged with the rapidity of lightning.” Morse and his assistant then spent several months sending messages across the telegraph day and night, showing how it could be used in a number of ways.

The telegraph office in Washington was moved to the post office in October 1844, and in March of the following year, Congress granted $8,000 for the expense and maintenance of the line under the postmaster general. Then, on April 1, 1845, the telegraph line was opened to the public. Samuel Morse was made superintendent of the system and an employee of the Post Office Department. The new service had a postage rate of one-quarter of one cent for each character of the message, paid by the sender. Once the messages were received at the other end, they were written down and given to postmen for delivery.

The initial rate had been set at half the price Morse had suggested, to encourage people to use it. It would be lowered even more the following year. However, few people actually used the telegraph service and proved unprofitable in its first year. Because it was unprofitable, Congress didn’t want to pay to establish more lines. But Morse and others recognized the importance and usefulness of the telegraph, so they formed their own company and built their own lines from their own funds. By late 1846, telegraph lines connected Washington and New York City, while other lines stretched to Boston and Pittsburgh.

Eventually, the private company took over operation of the Washington-Baltimore line, authorized to do so as long as they didn’t charge the government for their service. From then until World War I, telegraph service would remain in private hands. Telegraph service remained in use through the end of the century but would come to an end in 2013.