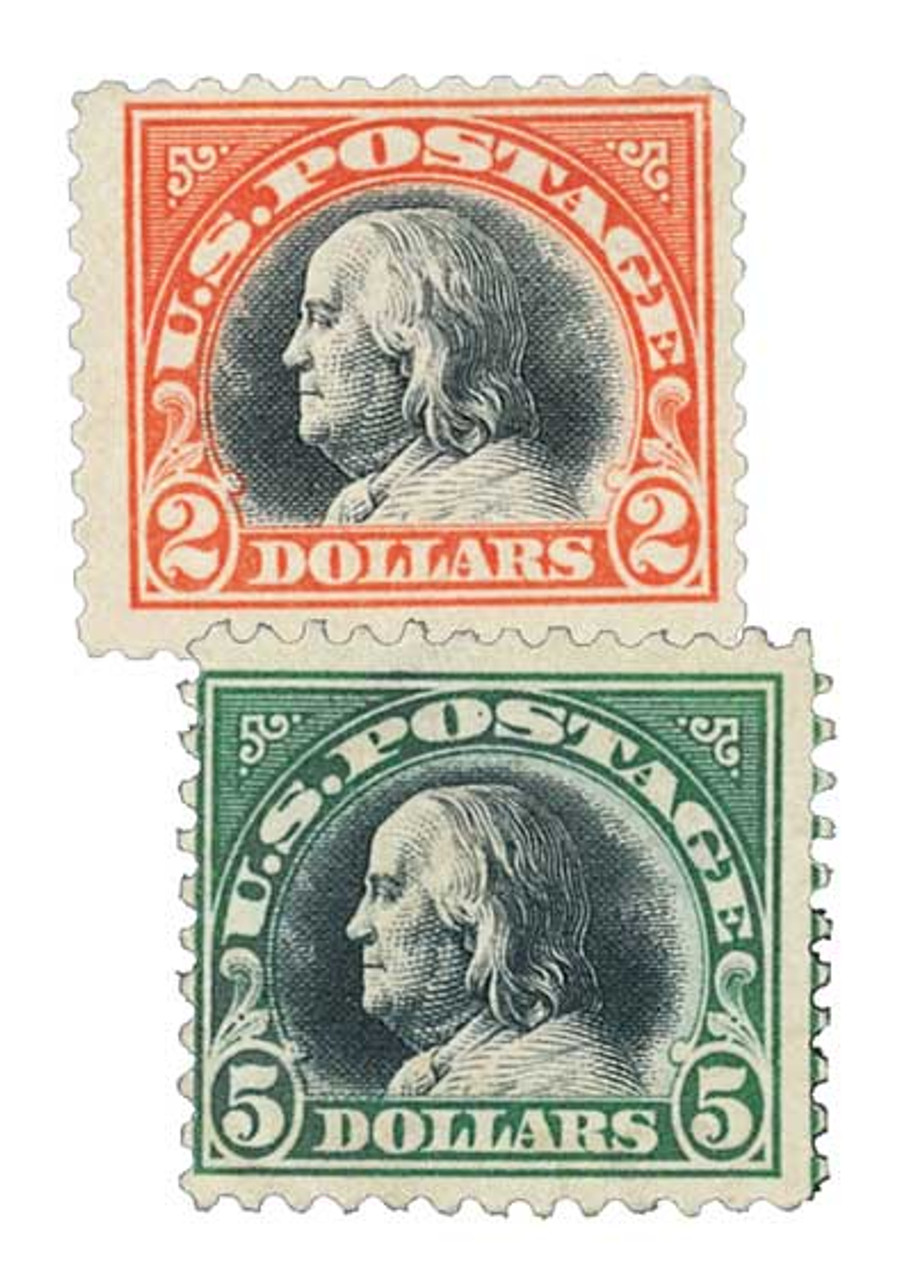

U.S. #523-24

1918 $2 and $5 Franklins

The $2 and $5 Franklin stamps were printed using a single plate. They were the first bi-colored definitive stamps in U.S. history. The perforation gauge had been changed to 11 the previous year, which defines this sixth major set in the Washington-Franklins.

The $2 Franklin stam... more

U.S. #523-24

1918 $2 and $5 Franklins

The $2 and $5 Franklin stamps were printed using a single plate. They were the first bi-colored definitive stamps in U.S. history. The perforation gauge had been changed to 11 the previous year, which defines this sixth major set in the Washington-Franklins.

The $2 Franklin stamp (U.S. #523) pictures the Founding Father in black with a striking orange red frame. The stamp had been requested earlier, but was delayed while the Bureau of Engraving and Printing struggled to fulfill other projects brought about by World War I.

In November of 1920, the $2 Franklin stamp suddenly appeared with a carmine frame, causing quite a buzz among stamp collectors. Many thought they’d discovered a color error.

Postal officials denied the rumors. Upon investigation, they learned the original specifications had called for a carmine frame, and that the earlier orange red Franklin stamp (U.S. #523) was actually the error.

Because the discovery was made more than two years after U.S. #523 had been issued, collectors who’d overlooked it scrambled to get the stamp. Many, however, had served their function and been discarded.

Relief Efforts Cause Unexpected Demand for $5 Stamp

Early in 1917, the Post Office was caught off guard by a sudden huge demand for high-value stamps. At that time, Americans were sending many shipments of machine parts to Russia by Parcel Post. Also, valuable shipments of Liberty Bonds required large amounts of postage.

To meet demand, the 1918 $5 Franklin stamp was issued. The stamp features a deep green frame and black central design on unwatermarked paper. A $2 Franklin stamp (U.S. #523) was also issued to meet the sudden demand for high-value stamps. The denominations were nearly identical in design, with different colors so help postal clerks distinguish them apart.

Because of its high face value and postal use, U.S. #524 has always been desirable. In “United States Postage Stamps 1902-1935,” philatelic author and legendary stamp expert Max Johl advised, “Only a limited number were issued and collectors would do well to buy their copies... as soon as possible, as this stamp will soon be among those ‘hard to get.’ ”

Happy Birthday Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin was born on January 17, 1706, in Boston, Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Franklin was the son of a soap and candle maker. As a youth, he learned these trades but found them unsatisfactory. So he became an apprentice to his brother James, a printer, at the age of 12. It was in this apprenticeship that Franklin started what he considered his primary, lifelong occupation – printing.

During this time Franklin also wrote many articles that were submitted and published under the pseudonym “Silence Dogood.” These writings demonstrated his unique wit, humor, and insight. However, when his brother discovered that Benjamin was the author of the articles, he refused to publish them. The two brothers quarreled frequently, and at the age of 17, Franklin ran away and settled in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Franklin’s arrival in Philadelphia has become a classic part of American folklore. The young man arrived in the city on a Sunday morning, tired and hungry. At a bakery, he asked for three pennies’ worth of bread, and received three loaves. He then bravely walked up Market Street with a loaf under each arm while eating the third. As he passed the door of the Read family, his future wife, Deborah Read, watched him walk by, and thought he made “a most awkward and ridiculous appearance.”