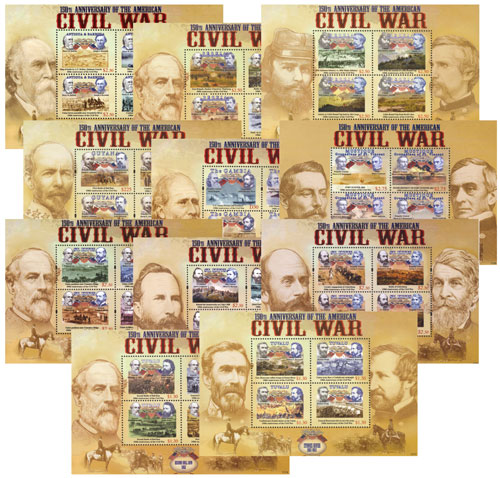

# 1178-82 - Complete Set, 1961-65 Civil War Centennial Series

4¢ Firing on Fort Sumter

City: Charleston, SC

Quantity: 101,125,000

Printed By: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Rotary press

Perforations: 11 x 1.5

Color: Light green

4¢ Shiloh

City: Shiloh, TN

Quantity: 124,865,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Perforations: 11 x 10 1/2

Color: Black on peach blossom

4¢ Gettysburg

City: Gettysburg, PA

Quantity: 79,905,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Giori Press

Perforations: 11

Color: Gray and blue

5¢ Battle of the Wilderness

City: Fredericksburg, VA

Quantity: 125,410,000

Printed By: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Giori Press

Perforations: 11

Color: Dark red and black

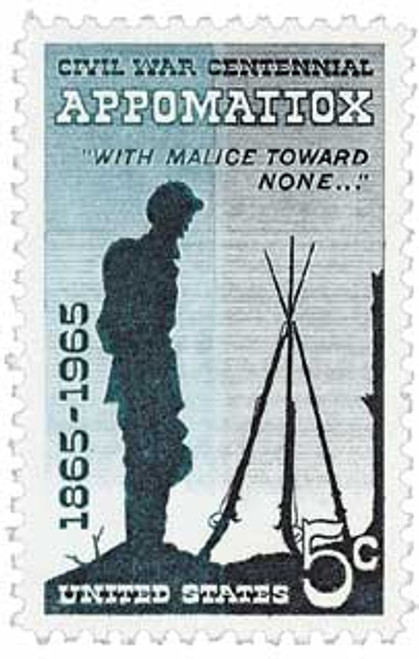

5¢ Appomattox

City: Appomattox, VA

Printed By: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Giori press

Perforations: 11

Quantity: 112,845,000

Color: Prussian blue and black

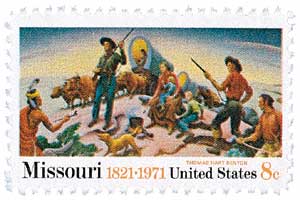

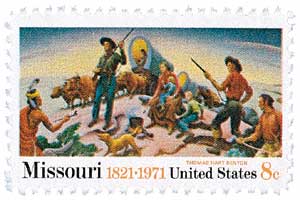

Battle Of Wilson’s Creek

On August 10, 1861, the first major battle in the Trans-Mississippi Theater of the Civil War was fought in Missouri.

Missouri was a border state that declared its neutrality early in the Civil War. Governor Claiborne F. Jackson, who was in favor of secession, called the state militia to drill near St. Louis. Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon of the Union’s Army of the West realized the governor had plans to storm the Federal arsenal in St. Louis, so he surrounded the militia. The militia surrendered and was marched through the streets of St. Louis. The crowd that gathered quickly turned violent, and the Union troops fired on them.

The next day, the Missouri State Guard was formed to protect the state from enemies. Lyon’s troops were considered enemies, and became the target of attack. By early August, American troops under the command of Lyon and Franz Sigel were camped in Springfield, Missouri while Confederate troops under Sterling Price and Benjamin McCulloch were about 10 miles away. Both sides planned an attack for August 10, though the Confederates postponed their plans when it began to rain the night before.

The Union Army of the West marched through the night in two columns until they reached their destination, then rested a few hours. At 5:00 a.m., Lyon’s men subdued a band of Confederate Cavalry and took the high ground, later known as “Bloody Hill.” When Sigel heard the gunfire, he started firing at the rear of the Confederate Army camped at Sharp Farm. The surprised soldiers fled into the woods with Sigel’s men in pursuit.

Confederate Generals McCulloch and Price launched their counterattacks at both locations. They tried three times to retake Bloody Hill, but were repulsed each time. General Lyon was killed during the second assault and Major Samuel D. Sturgis took command. After the third attempt, both sides were low on ammunition and the soldiers were exhausted. The Union Army retreated before the Confederates could attack a fourth time.

General Sigel was sure he had defeated the Confederates, so he did not send skirmishers to protect his flanks. When the Confederates approached for a counterattack, Sigel’s men mistook them for Union troops because their uniforms looked similar to those of the 3rd Iowa Infantry. By the time the Union soldiers realized their mistake, the Confederates were only 40 yards away. Sigel and his men fled back to Springfield.

The Union Army of the West lost about one fourth of its men in the six-hour battle, and Brigadier General Lyon was the first Union general to lose his life in the Civil War. The much larger Confederate Army suffered the same number of casualties, which was about 12% of their troops. Price and his Missouri State Guard continued to northern Missouri, where their victories gave support to those who wanted the state to join the Confederacy. But the majority of residents resisted, and Missouri remained in the Union throughout the war.

4¢ Firing on Fort Sumter

City: Charleston, SC

Quantity: 101,125,000

Printed By: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Rotary press

Perforations: 11 x 1.5

Color: Light green

4¢ Shiloh

City: Shiloh, TN

Quantity: 124,865,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Perforations: 11 x 10 1/2

Color: Black on peach blossom

4¢ Gettysburg

City: Gettysburg, PA

Quantity: 79,905,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Giori Press

Perforations: 11

Color: Gray and blue

5¢ Battle of the Wilderness

City: Fredericksburg, VA

Quantity: 125,410,000

Printed By: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Giori Press

Perforations: 11

Color: Dark red and black

5¢ Appomattox

City: Appomattox, VA

Printed By: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Giori press

Perforations: 11

Quantity: 112,845,000

Color: Prussian blue and black

Battle Of Wilson’s Creek

On August 10, 1861, the first major battle in the Trans-Mississippi Theater of the Civil War was fought in Missouri.

Missouri was a border state that declared its neutrality early in the Civil War. Governor Claiborne F. Jackson, who was in favor of secession, called the state militia to drill near St. Louis. Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon of the Union’s Army of the West realized the governor had plans to storm the Federal arsenal in St. Louis, so he surrounded the militia. The militia surrendered and was marched through the streets of St. Louis. The crowd that gathered quickly turned violent, and the Union troops fired on them.

The next day, the Missouri State Guard was formed to protect the state from enemies. Lyon’s troops were considered enemies, and became the target of attack. By early August, American troops under the command of Lyon and Franz Sigel were camped in Springfield, Missouri while Confederate troops under Sterling Price and Benjamin McCulloch were about 10 miles away. Both sides planned an attack for August 10, though the Confederates postponed their plans when it began to rain the night before.

The Union Army of the West marched through the night in two columns until they reached their destination, then rested a few hours. At 5:00 a.m., Lyon’s men subdued a band of Confederate Cavalry and took the high ground, later known as “Bloody Hill.” When Sigel heard the gunfire, he started firing at the rear of the Confederate Army camped at Sharp Farm. The surprised soldiers fled into the woods with Sigel’s men in pursuit.

Confederate Generals McCulloch and Price launched their counterattacks at both locations. They tried three times to retake Bloody Hill, but were repulsed each time. General Lyon was killed during the second assault and Major Samuel D. Sturgis took command. After the third attempt, both sides were low on ammunition and the soldiers were exhausted. The Union Army retreated before the Confederates could attack a fourth time.

General Sigel was sure he had defeated the Confederates, so he did not send skirmishers to protect his flanks. When the Confederates approached for a counterattack, Sigel’s men mistook them for Union troops because their uniforms looked similar to those of the 3rd Iowa Infantry. By the time the Union soldiers realized their mistake, the Confederates were only 40 yards away. Sigel and his men fled back to Springfield.

The Union Army of the West lost about one fourth of its men in the six-hour battle, and Brigadier General Lyon was the first Union general to lose his life in the Civil War. The much larger Confederate Army suffered the same number of casualties, which was about 12% of their troops. Price and his Missouri State Guard continued to northern Missouri, where their victories gave support to those who wanted the state to join the Confederacy. But the majority of residents resisted, and Missouri remained in the Union throughout the war.