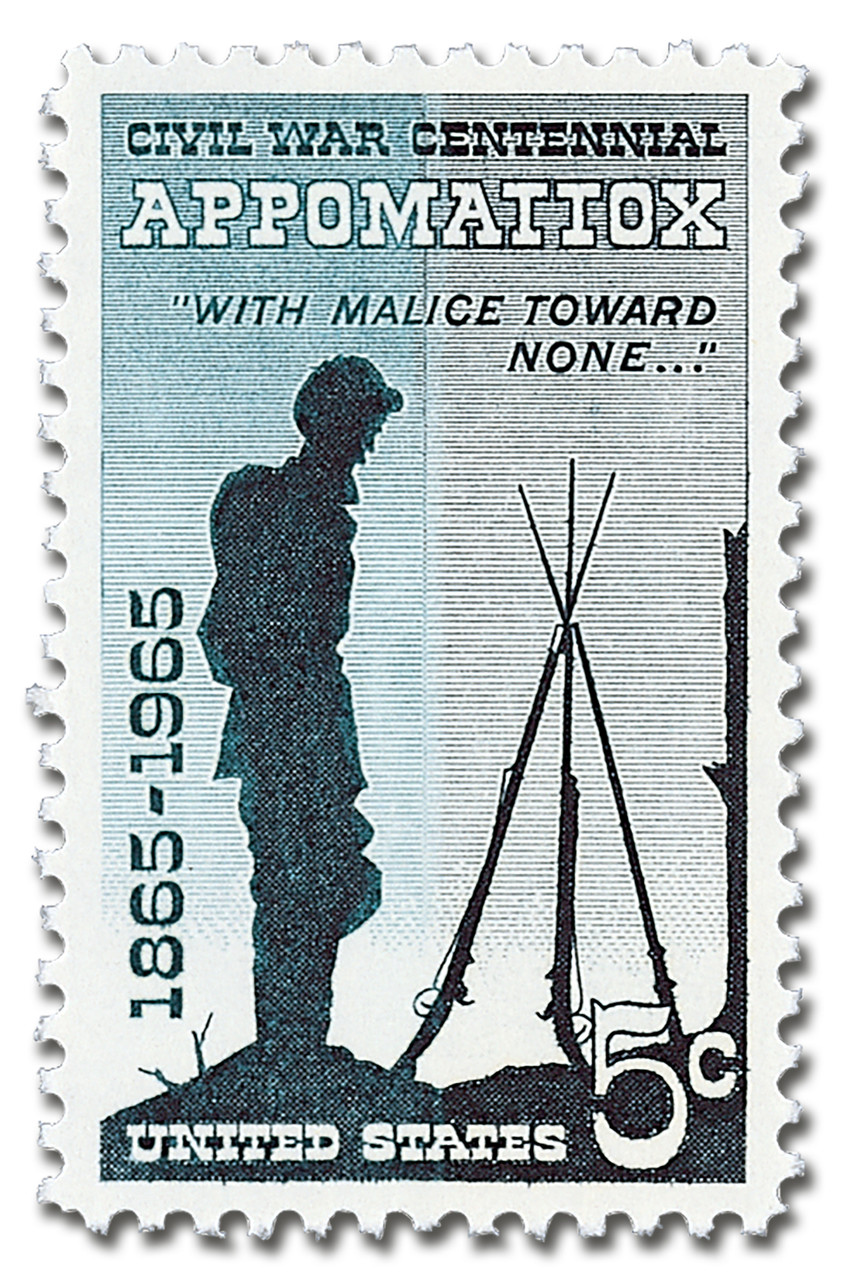

U.S. #1182

5¢ Appomattox

Civil War Centennial Series

Issue Date: April 9, 1965

City: Appomattox, VA

Printed By: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Giori press

Perforations: 11

Quantity: 112,845,000

Color: Prussian blue and black

On April 9, 1865, Robert E. Lee surrendered his Army of Northern... more

U.S. #1182

5¢ Appomattox

Civil War Centennial Series

Issue Date: April 9, 1965

City: Appomattox, VA

Printed By: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Giori press

Perforations: 11

Quantity: 112,845,000

Color: Prussian blue and black

On April 9, 1865, Robert E. Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia to Ulysses S. Grant, effectively ending the Civil War.