U.S. 1650

1976 Louisiana Flag

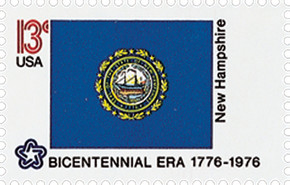

State Flags

American Bicentennial Series

• First time a sheet 50 had all different stamp designs

• Part of the American Bicentennial Series

Stamp Category: Commemorative

Series: American Bicentennial Series

Value: 13¢ First-class postage rate

First Day of Issue: February 23, 1976

First Day City(s)... more

U.S. 1650

1976 Louisiana Flag

State Flags

American Bicentennial Series

• First time a sheet 50 had all different stamp designs

• Part of the American Bicentennial Series

Stamp Category: Commemorative

Series: American Bicentennial Series

Value: 13¢ First-class postage rate

First Day of Issue: February 23, 1976

First Day City(s): Washington, DC

Quantity Issued: 8,720,100 (panes of 50)

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Photogravure

Format: Sheet of 50

Perforations: 11

Why the stamp was issued:

The United States Postal Service celebrated the American Bicentennial with a full pane of the Union’s fifty state flags.

About the stamp design:

French explorer Pierre LeMoyne d’Iberville sailed along the Gulf of Mexico in search of the mouth of the mighty Mississippi. Everywhere LeMoyne looked, he saw colonies of pelicans. Hoping to attract permanent settlers to Louisiana, Iberville took 24 “well-bred” birds back to France.

The pelicans on the Louisiana state flag symbolize the waterways and harbors, which are the state’s lifeblood. The Mississippi, for which Iberville searched, empties into the Gulf of Mexico at New Orleans.

In Colonial times, traders and fur trappers traveled the river by canoe. By the 1800s, paddle-wheel steamboats carried cotton south to New Orleans and Baton Rouge for shipment throughout the world. Louisiana became a center for trade, and by 1840, New Orleans was the wealthiest city in the nation. By the mid-19th century, Louisiana became a starting point for western settlement. Immigrants traveled north on the Mississippi to meet wagon trains to California and Oregon.

It has been over 300 years since Iberville discovered the mouth of the Mississippi. The days of the canoe and steamboat are gone – replaced by barges and oceanliners. The pelicans, however, can still be found nesting on Louisiana’s Gulf Shore.

About the printing process:

Printed by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing on their seven-color Andreotti gravure press (601) which was their work horse for multicolored stamps.

About the American Bicentennial Series:

In the 1970s, America celebrated its 200th anniversary with hundreds of national events commemorating the heroes and historic events that led to our nation’s independence from Great Britain. The U.S. Postal Service issued 113 commemorative stamps over a six-year period in honor of the U.S. bicentennial, beginning with the American Revolution Bicentennial Commission Emblem stamp (U.S. #1432). As a group, the Bicentennial Series chronicles one of our nation’s most important chapters, and remembers the events and patriots who made the U.S. a world model for liberty.

Several of the stamps honored colonial life – craftsmen and communication. Other stamps honored important battles including Lexington and Concord, Bunker Hill, and Saratoga. Significant events such as the Boston Tea Party, the meeting of the First Continental Congress, and the Declaration of Independence were featured as well. The stamps also honored many significant people such as George Washington, Sybil Ludington, Salem Poor, and the Marquis de Lafayette.

Many of the stamps feature classic artwork. For instance, the set of four souvenir sheets picture important events recreated by noted artists such as John Trumbull. The Bicentennial Series also includes an important US postal first – the first 50-stamp se-tenant – featuring all 50 state flags. The format proved to be popular with collectors, and has been repeated many times since.

The American Bicentennial Series is packed with important US history – it tells the story of our nation’s fight for independence through stamps.

History the stamp represents:

On April 30, 1812, Louisiana became America’s 18th State.

Although Indians lived in the lower Mississippi River valley as far back as 10,000 years ago, little evidence remains of their culture. The first organized society, called the Poverty Point site, may date as far back as 700 B.C.

In 1542, Spanish Explorer Hernando de Soto explored the region searching for gold. However, no gold was found in the area, and Spain made no further attempts at exploration.

In 1682, nearly 140 years after de Soto’s journey, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de la Salle, led a group of French explorers on an expedition down the Mississippi River. When he arrived in the lower Mississippi valley on April 9, Cavelier claimed the entire region for France. The new territory was named Louisiana, after France’s King Louis XIV.

Even though Louisiana was growing in population, France was not satisfied with the amount of income it was producing. In 1762, France secretly ceded Louisiana to Spain. Many colonists were outraged at this decision. However, even after a group of colonists drove the Spanish governor from the colony, Spain still held a firm control.

No actual Revolutionary War battles were fought on Louisiana soil. However, the colony did play an important role in the war effort. Spain allowed the Continental Congress to use the Louisiana port of New Orleans. Throughout the war, supplies were shipped from New Orleans to the struggling British Colonies. This pipeline played a major part in America’s victory over Great Britain.

Following the Revolutionary War, Louisiana’s economy flourished. Étienne de Boré invented a method of processing sugar on a large scale. This development allowed Louisiana to benefit from its abundance of sugar cane.

In the early 1800s, Napoleon Bonaparte sought to create a great French empire in the New World, so he reacquired Louisiana from Spain. The center of the empire was to be the nation of Hispaniola. Napoleon envisioned that the Mississippi Valley would be the trade center of the new empire, shipping food and supplies from America to Hispaniola.

At this time, however, Hispaniola was in the midst of a slave revolt. This revolt had to be put down before French control could be restored. In an attempt to end the revolt, Napoleon sent a large army to Hispaniola. Although there were considerable French victories on the battlefield, many soldiers died from disease. Because of these heavy losses, Napoleon decided to abandon Hispaniola and, in turn, his dream of an empire in the New World.

With Hispaniola gone, Napoleon had little use for Louisiana. This, coupled with the fact that war was imminent in Europe and he couldn’t spare troops to defend Louisiana, caused Napoleon to offer the land for sale to the United States. This pleased James Monroe and Robert Livingston, who had been sent to France to negotiate for the port city of New Orleans and some surrounding regions. After a small hesitation, because there was no time to consult the President, the pair decided to purchase the larger territory for $15 million. The newly acquired land (which would someday make up all or part of fifteen states) doubled the size of the existing United States and guaranteed free navigation of the Mississippi River.

Once the purchase was complete, the issue of statehood arose quickly, as part of the purchase itself stated, “inhabitants of the ceded territory shall be incorporated into the Union of the United States and admitted as soon as possible.” However, the New Orleans Territory (as it was known) was starkly different from the rest of the states. It had a heritage based on French and Spanish traditions, unlike the eastern states that were largely steeped in British practices.

In 1810 the territory submitted its petition for statehood. After the Senate accepted it, they were ordered to hold a convention and draft a constitution. Border disputes drew out the process, but Louisiana was ultimately admitted to the Union on April 30, 1812.