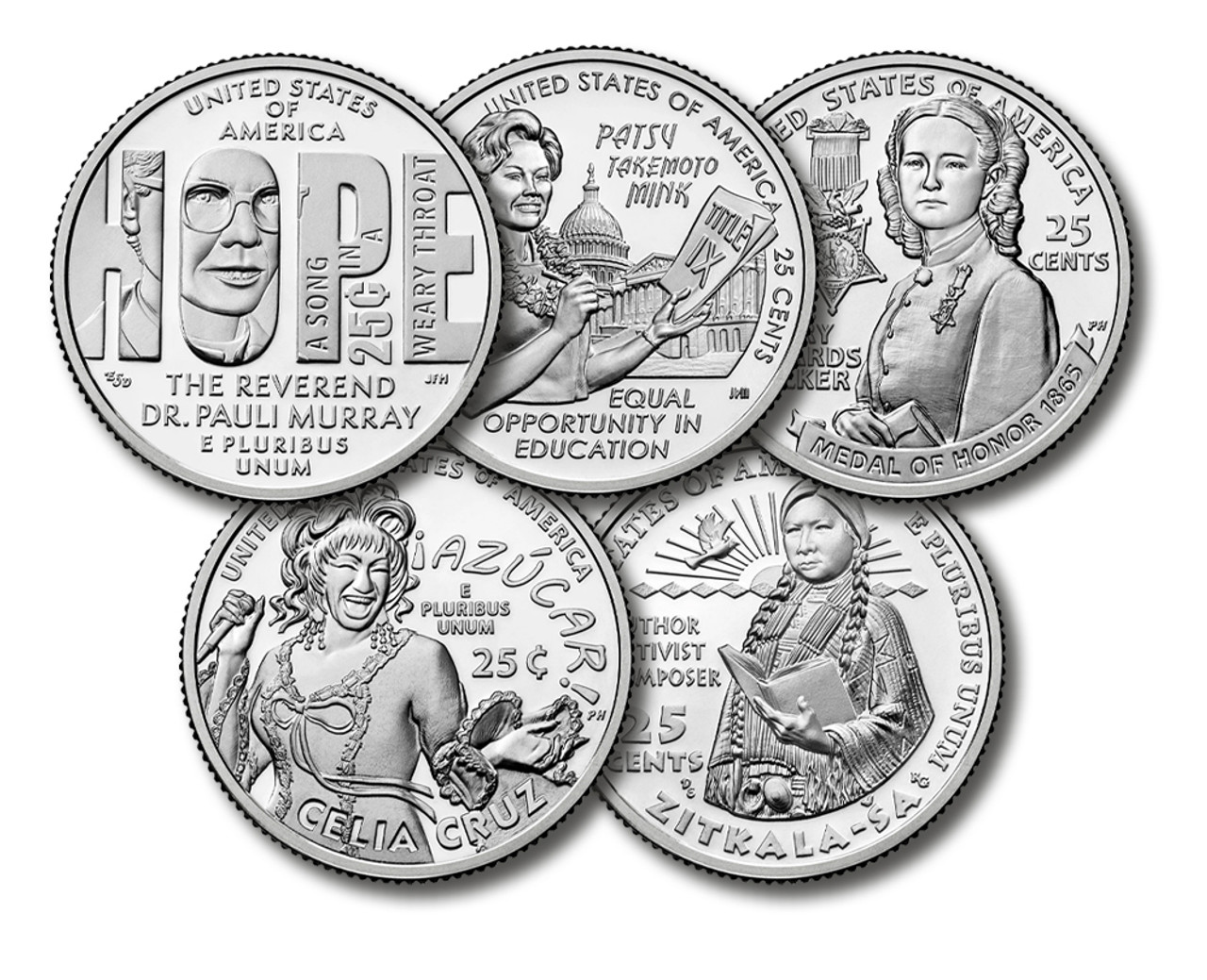

Get this set of 5 American Women Quarters Struck at the Philadelphia Mint in 2024

This set of five quarters were issued in 2024 as part of the first series of US coins to honor the achievements of women. The reverse designs on the quarters feature Reverend Dr. Pauli Murray, Patsy Tak... more

Get this set of 5 American Women Quarters Struck at the Philadelphia Mint in 2024

This set of five quarters were issued in 2024 as part of the first series of US coins to honor the achievements of women. The reverse designs on the quarters feature Reverend Dr. Pauli Murray, Patsy Takemoto Mink, Dr. Mary Edwards Walker, Celia Cruz, and Zitkala-Sa. These coins were produced at the Philadelphia Mint.

About the American Women Quarters Program

The American Women Quarters Program is a multi-year tribute to women from diverse backgrounds, races, ethnicities, and parts of the US. They were chosen for their contributions to the abolition of slavery, civil rights activism, roles in government, as well as expertise in science, the arts, humanities and much more.

From 2022 through 2025, five new coins were released each year. Each coin features a distinctive reverse design honoring an American woman, along with her name, “UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,” “E PLURIBUS UNUM,” and “QUARTER DOLLAR.” The obverse side showcases a new design of George Washington.

These are the women honored on these quarters:

On the quarter, Reverend Dr. Pauli Murray is pictured within the word “HOPE.” A line from her poem “Dark Testament” is also inscribed on the coin. This coin was minted at the Denver Mint

Anne Pauline Murray (1910-1985) was an excellent student, who graduated from high school at age 15. She graduated from Hunter College during the Great Depression and found it difficult to find a job. While working various jobs, she began publishing her poetry. During this time, she also began using the nickname Pauli.

In the 1940s, Murray worked with the Workers Defense League trying to free an imprisoned sharecropper. She gave a speech in Richmond, Virginia, and a Howard Law School professor was in the audience. After the speech, the professor encouraged Murray to apply to the school, which she did. As a student, she wrote a paper challenging a Supreme Court decision. Her challenges became part of the Brown vs. Board of Education case that led to desegregation.

In 1977, Murray added another title besides poet, author, and lawyer, when she became the first African American woman to become an Episcopal priest. She lived her life in service to those facing discrimination. She knew firsthand how it felt and was determined to stop it wherever she could.

The image on the Patsy Takemoto Mink quarter shows her holding the TITLE IX legislation that she fought for in Congress. The lei around her neck represents her home state of Hawaii. Behind her is the Capitol Building.

Patsy Takemoto (1927-2002) was born in Hawaii before it became part of the United States. After graduating from high school as valedictorian, she went to college in Pennsylvania and Nebraska. Takemoto faced racial discrimination, so she returned to Hawaii to finish her schooling. She wanted to be a doctor but wasn’t accepted to any medical schools. Instead, Patsy studied law at the University of Chicago.

At Law School, she met John Mink, and they were later married. After graduation, they returned to Hawaii. Though Patsy passed the bar exam, she couldn’t find a job because of her mixed marriage. She started her own practice, becoming the first Japanese-American woman to practice law in Hawaii.

Shortly after Mink became an established lawyer, Hawaii was admitted to the United States. She set her sites on Congress. Though her first campaign was unsuccessful, she won a seat in the House of Representatives in 1964. In Congress, Mink fought for gender and racial equality and was one of the key supporters of Title IX.

In 1972, Mink was asked by the Oregon Democrats to run of US President. Though her campaign didn’t gain much traction, she was still the first Asian-American woman to seek the office. Patsy returned to Congress and served a total of 12 terms. She spent much of her time advocating for equality in schools and in society. After her death, the Title IX law she worked hard to pass was renamed the Patsy T. Mink Equal Opportunity in Education Act.

The Dr. Mary Edwards Walker quarter shows her holding her pocket surgical kit. She is wearing her Medal of Honor and surgeon’s pin. A detail of her medal is on the left side of the image

Mary Edwards Walker was born on November 26, 1832, and was raised in a progressive household where her parents encouraged her to be a free thinker. Walker graduated from Syracuse Medical College at the age of 21 after attending three 13-week semesters of training. She then married a fellow physician and set up a medical practice in Rome, New York, but both the business and the marriage failed.

Walker tried to join the Union Army when the Civil War began but was denied a commission, so she volunteered as a surgeon. At the time, the Army didn’t allow female surgeons, so she was admitted as a nurse. Walker eventually became acting assistant surgeon making her the first female surgeon in the US Army. For two years, Walker served at the front lines. In 1863, she was appointed assistant surgeon in the Army of the Cumberland and eventually the 52nd Ohio Infantry.

Walker also served as a spy and crossed Confederate lines to treat civilians until she was taken prisoner while helping a Confederate doctor amputate a soldier’s leg. Imprisoned for four months, she was released and spent the rest of the Civil War treating patients at a prison for women in Louisville and an orphanage in Tennessee.

On November 11, 1865, President Andrew Johnson signed a bill presenting Walker with the Congressional Medal of Honor for Meritorious Service. The measure recognized her contribution to the Union cause without awarding her an Army commission. In 1917, Congress revised the Medal of Honor standards to limit eligibility to those who had done “actual combat with an enemy.” Feisty to the end, 84-year-old Walker refused to return the medal and wore it every day until her death in 1919. In 1977, an Army board reinstated the award posthumously.

Mary Edwards Walker’s father was actively involved in many of the reform movements that took place in upstate New York during the early and mid-1800s. He supported the abolition of slavery and education for women, and believed the restrictive clothing styles for women hampered their ability to succeed. Mary was also an advocate of women’s rights and believed in dress reform. She wore trousers and a man’s jacket on her wedding day and kept her maiden name.

Celia Cruz can be seen on the quarter enjoying herself while performing. Her catchphrase “¡AZÚCAR!” is on the right side of the image.

Celia Cruz (1925-2003) was an internationally known singer and became known as the Queen of Salsa. Born in Cuba, she began winning talent contests for her singing. Though she trained to be a teacher, her love of music kept drawing her back. She sang on the radio and with local bands. Cruz became known for her versatility with music styles, but she faced discrimination because of her Cuban and African ancestry.

When Cuba was thrown into a revolution and Fidel Castro came into power, Cuban artists were expected to produce songs that endorsed the new regime. Refusing to yield to the new mandate, Cruz and her band flew to Mexico in 1962 for a concert tour and never returned to Cuba. She eventually settled in the US.

By the 1970s, Cruz became associated with the salsa style of music. Her catchphrase "¡Azúcar!” meaning “Sugar!” became a symbol of the music genre.

Cruz continued to perform and record her unique music throughout her life. During her career, she received two Grammy Awards. She was also awarded the National Endowment for the Arts award by President Bill Clinton in 1994. Celia Cruz will always be remembered for the impact she made on Latin music, bringing the sound to fans across Latin America and the United States.

The Zitkala-Ša coin shows her in traditional Yankton Sioux dress. The book she’s holding represents her writing career and her activism for Native American rights. The sun in the background is a nod to her The Sun Dance Opera. The cardinal points to her native name, which translates “Red Bird.”

Zitkala-Ša. (1876-1938) was given the name Gertrude Simmons Bonnin. Born on an Indian reservation in South Dakota, she was sent to a Quaker school in Indiana when she was eight years old. Here she learned to read, write, and play violin, but Zitkala-Ša was forced to assimilate into American culture. Upon returning to the reservation, she realized she no longer fit in with her people and returned to school. After graduation, Zitkala-Ša continued her education at Earlham College, where she excelled in writing and giving speeches. During this time, she began collecting traditional Native American stories and translating them so children could read them.

Zitkala-Ša later became a music teacher at an Indian school in Pennsylvania. After writing critical articles about the forced assimilation of Native Americans, she was dismissed from her position. She then returned to the reservation, where she cared for her mother and gathered more stories. Zitkala-Ša published the stories, as well as accounts of her life. In the early decades of the 20th century, her writing turned more political. Around this time, she moved to Washington, DC, to work as the national secretary of the Society of American Indians. In this role, she criticized the treatment of Native American children by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Her work in support of Native Americans lead to the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924. Though Native Americans were now considered US citizens, many were denied the right to vote. Zitkala-Ša and her husband established the National Council of American Indians to fight for this right. She was also an activist for women’s rights. For the remainder of her life, Zitkala-Ša fought for all Americans to be afforded the rights of full citizenship.